Who would put out a landfill fire near Moody? That question consumed officials for weeks

The EPA put out signs linking to a web page with information about the air quality and their progress on putting out a fire at a landfill near Moody.

Frank Read remembers the first night he saw the fire at the private landfill across the street from his home in western St. Clair County.

“You could see the flames 10 or 20 feet above the treeline that night,” Read said.

The fire at Environmental Landfill, Inc. which began in late November, would blanket the surrounding area with smoke and odors, especially when it was cold or cloudy.

In a Facebook group that formed as an information hub for affected community members, people shared how they used painter’s tape to secure cracks around windows and doors to keep the smoke out of their homes. They discussed spending hundreds of dollars on air purifiers and scrubbers. They commiserated about smoke-related health issues — headaches, coughing, shortness of breath. People living miles away could smell the fumes.

Read said some days the smoke was so sickening outdoor chores were impossible.

“You couldn’t be outside for 15 minutes without being choked out,” Read said.

Throughout December, residents sent a deluge of complaints to public officials while the fire continued to burn. Yet weeks of bureaucratic delay meant it was mid-January before an effective effort to put out the fire began.

“I emailed the governor, I sent out and called, I can’t tell you how many people and pretty much got stonewalled everywhere I went. So it was frustrating,” Read said.

A unique situation

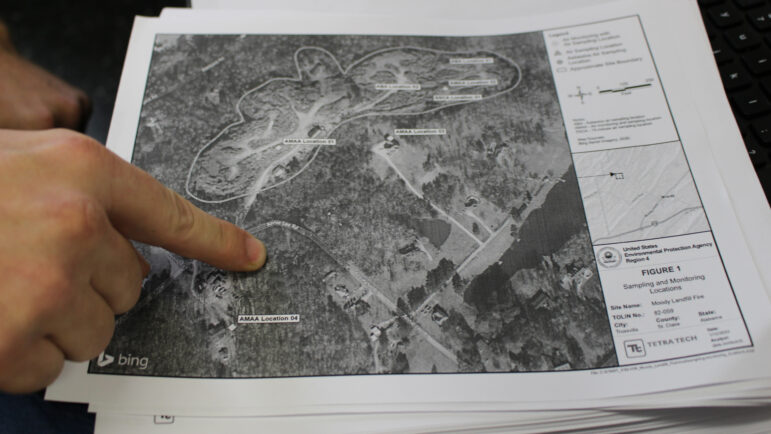

The day after Thanksgiving, the Moody Fire Department responded to the blaze. They called the Alabama Forestry Commission for assistance. The forestry commission was able to secure a border to keep the fire from spreading, but it didn’t take them long to realize that the burning area — which encompassed more than 13 acres, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — was beyond what they had the capacity to put out.

“Everybody, the fire department and the forestry commission knew pretty quick, this is not something we normally do. We don’t fight landfill fires,” said Stan Batemon, chairman of the St. Clair County Commission.

When it became clear that neither the landowner nor the site’s current operator would be able to handle such a large fire, the Alabama Department of Environmental Management said that the county would be responsible. But, according to Batemon, the county didn’t even have authority to enter the private property. He said a back-and-forth ensued among ADEM, St. Clair County’s attorney and attorneys in the governor’s office about who could take action.

“If ADEM keeps saying that this was the county’s responsibility, and we keep saying it’s not, then that’s called finger pointing,” Batemon said.

A false start

In early January, St. Clair County declared a local state of emergency, a move that Batemon said was ultimately useless.

“Declaring an emergency on the county level didn’t do anything to loosen the county’s resources up to be able to go fight it,” Batemon said.

What they needed was an emergency declaration from the governor’s office, which would authorize the county to go on private property and use public funds to put out the fire.

In the weeks following, the county’s engineer gathered bids from contractors who said they could tackle the mostly underground fire. The county compiled them in a letter they planned to send to the state asking for Gov. Kay Ivey to declare a state of emergency. That letter was never sent, Batemon said, because the governor’s office told them not to send it.

On Jan. 18, Ivey announced that she’d declared a limited state of emergency, which would authorize local officials to take action.

“It’s never too late to do a state of emergency because that frees up resources that locals can have and all the authorities that need authority get it, so they’re in good shape,” Ivey said at a public event days after she’d announced the declaration.

But hours after Ivey’s emergency declaration, ADEM announced that the EPA would be taking the lead in extinguishing the fire, saying that neither ADEM nor the county had the resources or expertise to choose a contractor.

Earlier in the month, ADEM asked the EPA to take air samples at the site. The results, which showed unsafe levels of hazardous chemicals in the smoke, authorized the federal agency to step in.

According to ADEM Director Lance LeFleur, the weeks of deliberation between the state, ADEM and the county government were a procedural necessity.

“It’s taken longer than anybody would have liked for it to take, but we had to go through the process of the state and local community examining and exhausting all of its options before bringing EPA in,” LeFleur said.

Unregulated and under the radar

According to state business records, Environmental Landfill has been operating as a natural waste dumping site — meaning it took plant waste such as trees — since at least 2007. Because the landfill only took vegetative waste, it was not required to be permitted or regularly inspected, state regulators said.

Surrounding the landfill is a wooded residential area with houses and mobile homes. Some of these residents had filed complaints about the landfill with ADEM in the years before the fire. The agency responded by sending inspectors to the site, issuing violations for unauthorized waste like construction demolition and tires, and even asking for a closure plan.

St. Clair County, Batemon says, has no zoning and planning or home rule, which is why the landfill operated for so long under the county’s radar. It’s also why the county had no legal authority to enter the site.

While Ivey and LeFleur defend the delay, pointing to the EPA’s success at abating the smoke, Batemon sees problems.

“I’m a little bit disappointed that the process we had in place as a government — as a combination of governments — wasn’t prepared to address this. We dropped the ball somewhere. So my goal is, is that new little rules and whatever comes out of this that this kind of thing doesn’t happen again,” Batemon said.

There are now at least two lawsuits against the owner and operator of the landfill, including at least one where LeFleur is also named as a defendant.

Residents agree that something needs to change in the future, whether that’s more authority for local governments or more regulations around vegetative waste landfills.

There’s less smoke coming from the site now as the EPA’s contractors continue to smother the burning areas with dirt, but residents are left wondering why it took so long to get to this point.

“The fire starts Sunday, I didn’t expect it to be out by Tuesday. I don’t think any resident did … What frustrated us is that it took them five weeks to decide who was going to be in charge of it. That’s the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard of,” Read said.

Park Fire in California could continue growing exponentially, Cal Fire officer says

Cal Fire has confirmed that over a hundred structures have been damaged in the Park Fire, which grew overnight near Chico, Calif. Difficult firefighting conditions are forecast through Friday night.

Checking in with Black voters in Georgia about the election, now that Biden is out

Some voters who could be key to deciding who wins Georgia. What do they think about Vice President Harris becoming the frontrunner in the race to be the Democratic nominee?

Tahiti’s waves are a matter of ‘life and death’ for surfing Olympics

Tahiti's Teahupo'o wave has a slew of riders for the Paris 2024 Olympics. NPR finds out why it's called one of the most dangerous waves.

Researchers are revising botanical names to address troubling connotations

Since the mid-1700s, researchers have classified life with scientific names. But some of them have problematic histories and connotations. The botanical community is trying to tackle this issue.

A spectacular opening ceremony wowed a global audience despite Paris’ on-and-off rain

The Paris Olympics opening ceremony wowed Parisians, fans and most everyone who was able to catch a glimpse of thousands of athletes floating down the Seine to officially begin the Games.

Kamala Harris faces racism and sexism as she moves closer to presidential nomination

As Vice President Kamala Harris ramps up her campaign for president, Republicans are trying out new — and old — attacks focused on her race and gender, including calling her a "DEI candidate."