As infertility rates rise, data shows much of the US lives in a ‘fertility desert’

Infertility rates across the world are on the rise with roughly 1 in 6 people experiencing it, according to a recent report published by the World Health Organization (WHO).

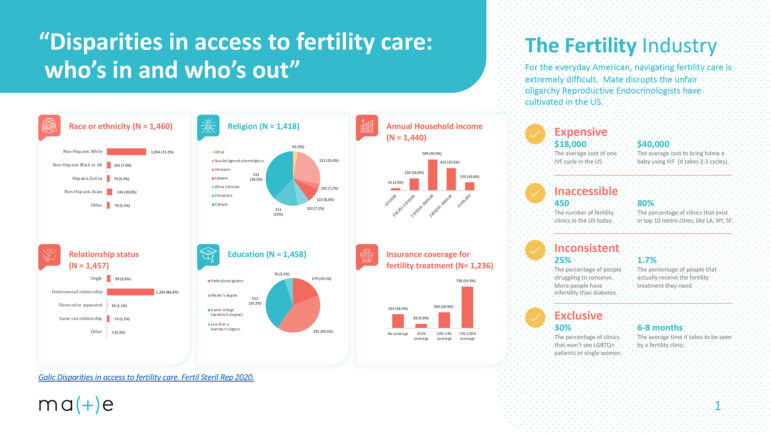

With that increase also comes an increase in people seeking treatment to help them start a family — services like in-vitro fertilization (IVF) — but data show that access to fertility care is out of reach for many in the U.S.

What is infertility?

Infertility is a broad term for a disease that is defined by the male or female reproductive system being unable to achieve pregnancy. In the U.S., about 11% of women and about 9% of men of childbearing age have infertility. In total, up to 15% of heterosexual couples are impacted by it, but the WHO’s data doesn’t account for LGBTQ+ couples or single people who want to have children.

The causes behind the increase are multi-faceted. Research consistently shows that lifestyle factors such as what you eat, how well you sleep, where you live and other behaviors can have a major impact on health and disease — including infertility.

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) has linked lifestyle factors such as obesity, strenuous physical labor, excessive exercise, substance use, heavy drinking, high blood pressure and others to increasing rates of infertility. NICHD research also shows that exposure to pollution in the environment can affect male and female fertility.

Fertility care deserts

In the U.S., there’s a serious problem with fertility care access. The issue is tied to two factors — cost and location — that feed off of each other.

More often than not, fertility treatment is not covered by public or private insurers, leaving patients paying upwards of $10,000, depending on the service — leaving fertility care out of reach for many.

The high cost of care has in turn driven most clinic locations to be concentrated in “high net-worth” areas where people are more likely to afford the expensive, specialized care. As a result, 80% of fertility care clinics in the country are located in New York City — 30% in just Manhattan alone.

Traci Keen, the founder of Mate Fertility, a company that helps OB-GYNs build out IVF labs and teaches them to offer other services, said this has led to vast “fertility deserts” in the U.S. where people just don’t have geographic access to treatment.

“You don’t have to go more than a little ways to find what we consider to be a fertility desert,” Keen said. “When we look at the rural South and the Gulf States, that only increases. When you look at the different levels of access to care on any front, it’s going to be even more exaggerated when it comes to fertility because of the costs.”

At 42 years old, Keen is the same age as the relatively-new fertility industry — she actually went to college with Elizabeth Carr, the first IVF baby born in the U.S. But since its inception, not much has changed.

“That’s just how the industry was built,” Keen said. “And as the need has increased — because we know that infertility rates are going up, we know that LGBTQ families want to do family building, we know that certain demographics of the population experience infertility at higher rates — those have not been adapted to or accommodated to.”

Significant disparities

In addition to fertility care deserts, studies also show that there are significant racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist among fertility patients accessing care.

Fewer Black and Hispanic women report ever having used medical services to become pregnant than white women. This is a result of many factors, including lower incomes on average among both demographics.

LGBTQ+ people also often face more difficulties in accessing fertility care, as they often do not meet definitions of “infertility” that would qualify them for covered services. Transgender people undergoing gender-affirming care may also not meet the criteria for “iatrogenic infertility” that would qualify them for covered fertility preservation.

A ‘catastrophic’ lack of doctors

Another driving factor behind the lack of access to fertility care is what Keen calls a “catastrophic” shortage of fertility doctors, known as reproductive endocrinologists (REIs), in the U.S.

This issue stems from the country holding one of the longest training processes in the world for these types of physicians. In order to provide IVF and other infertility treatments, doctors must generally go through four years of medical school, four years of residency, and another three years of fellowship in reproductive endocrinology. The total 11 years of education often deters would-be REIs from specializing in the field.

Because of this, the U.S. only trains about 45 doctors a year to provide infertility services. And as a similar number of REIs retire each year — but demand for IVF continues to increase — the result is that even with private companies like Mate Fertility offering specialized services, there aren’t near enough providers to meet the demand.

“In 2021, we did about 300,000 IVF cycles in the United States,” Keen says. “Just to meet demand, we would have needed to do 3 million.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.

40 years after ‘Purple Rain,’ Prince’s band remembers how the movie came together

Before social media, the film Purple Rain gave audiences a peak into Prince’s musical life. Band members say the true genesis of the title song was much less combative than the version presented in the film.

Park Fire in California could continue growing exponentially, Cal Fire officer says

Cal Fire has confirmed that over a hundred structures have been damaged in the Park Fire, which grew overnight near Chico, Calif. Difficult firefighting conditions are forecast through Friday night.

Checking in with Black voters in Georgia about the election, now that Biden is out

Some voters who could be key to deciding who wins Georgia. What do they think about Vice President Harris becoming the frontrunner in the race to be the Democratic nominee?

Tahiti’s waves are a matter of ‘life and death’ for surfing Olympics

Tahiti's Teahupo'o wave has a slew of riders for the Paris 2024 Olympics. NPR finds out why it's called one of the most dangerous waves.

Researchers are revising botanical names to address troubling connotations

Since the mid-1700s, researchers have classified life with scientific names. But some of them have problematic histories and connotations. The botanical community is trying to tackle this issue.

A spectacular opening ceremony wowed a global audience despite Paris’ on-and-off rain

The Paris Olympics opening ceremony wowed Parisians, fans and most everyone who was able to catch a glimpse of thousands of athletes floating down the Seine to officially begin the Games.