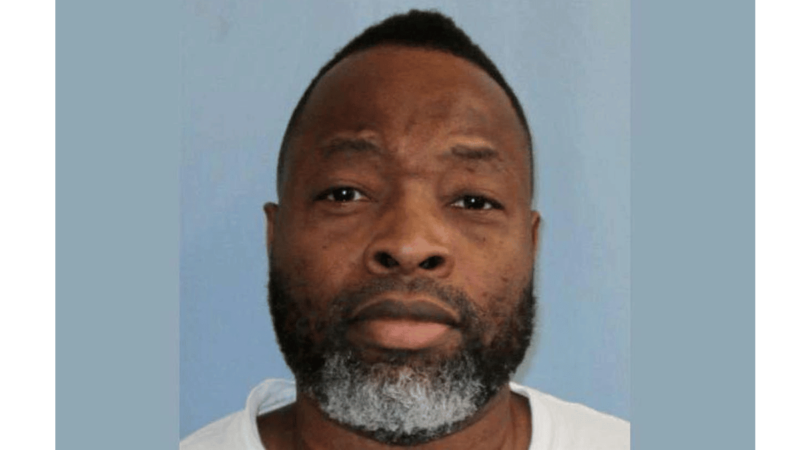

Alabama man’s execution was botched, advocacy group alleges

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Alabama corrections officials apparently botched an inmate’s execution last month, an anti-death penalty group alleges, citing the length of time that passed before the prisoner received the lethal injection and a private autopsy indicating his arm may have been cut to find a vein.

Joe Nathan James Jr. was put to death July 28 at an Alabama prison for the 1994 shooting death of his former girlfriend. The execution was carried out more than three hours after the U.S. Supreme Court denied a request for a stay.

“Subjecting a prisoner to three hours of pain and suffering is the definition of cruel and unusual punishment,” Maya Foa, director of Reprieve US Forensic Justice Initiative, a human rights group that opposes the death penalty, said in a statement. “States cannot continue to pretend that the abhorrent practice of lethal injection is in any way humane.”

The Alabama Department of Forensic Science declined a request to release the state’s autopsy of James, citing an ongoing review that happens after every execution. Officials have not responded to requests for comment on the private autopsy, which was first reported by The Atlantic.

At the time of the execution, Alabama Corrections Commissioner John Hamm told reporters that “nothing out of the ordinary” happened. Hamm said he wasn’t aware of the prisoner fighting or resisting officers. The state later acknowledged that the execution was delayed because of difficulties establishing an intravenous line, but did not specify how long it took.

Dr. Joel Zivot, a professor of anesthesiology at Emory University and an expert on lethal injection who witnessed the private autopsy, said it looked like there were numerous attempts to connect a line.

Zivot said he saw “multiple puncture sites on both arms” and two perpendicular incisions, each about 3 to 4 centimeters (1 to 1.5 inches) in length, in the middle of the arm, which he said indicated that officials had attempted to perform a “cutdown,” a procedure in which the skin is opened to allow a visual search for a vein. He said the cutdown is an old-style medical intervention rarely performed in modern medical settings, and that it would be painful without anesthesia. He also said he saw evidence of intramuscular injections not in the vicinity of a vein.

The Alabama Department of Corrections prison system issued a written statement in which it noted that “protocol states that if the veins are such that intravenous access cannot be provided, the team will perform a central line procedure,” which involves placing a catheter in a large vein. “Fortunately, this was not necessary and with adequate time, intravenous access was established,” the statement said.

Alabama does not allow witnesses from news outlets to watch the preparations for a lethal injection. They get their first glimpse of the execution chamber when an inmate is already strapped to the gurney with the IV line connected.

A reporter for The Associated Press who attended the execution observed that James did not respond when the warden asked if he had final words. His eyes remained closed except for briefly fluttering at one point early in the procedure.

Lawyers who spoke with James by telephone said they were disturbed by his reported lack of movements and raised questions about what happened before the lethal injection. Hamm said James was not sedated.

“That wasn’t the Joe that I knew. He always had something to say. He always wanted to be in control,” said James Ranson, the attorney who helped James file his appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court. “The fact that he did not give any sort of reaction … and that he didn’t open his eyes, tells me something was up,” Ranson said.

John Palombi, a federal defender who spoke with James twice on the day of his execution, said James, “was certainly alert” earlier in the day.

The Atlantic quoted a friend of James as saying that the inmate had planned to make a final statement.

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, a national nonprofit organization that analyzes issues concerning capital punishment, said the delay between the Supreme Court’s go-ahead and the execution, combined with the autopsy, points to a “botched execution, and it is among the worst botches in the modern history of the U.S. death penalty.”

“This execution is Exhibit A as to why execution secrecy laws are intolerable,” Dunham wrote in an email to the AP. “The public is entitled to know what went on here — and what goes on in all Alabama executions — from the instant the execution team begins the process of physically preparing the prisoner for the lethal injection until the moment the prisoner dies.”

40 years after ‘Purple Rain,’ Prince’s band remembers how the movie came together

Before social media, the film Purple Rain gave audiences a peak into Prince’s musical life. Band members say the true genesis of the title song was much less combative than the version presented in the film.

Park Fire in California could continue growing exponentially, Cal Fire officer says

Cal Fire has confirmed that over a hundred structures have been damaged in the Park Fire, which grew overnight near Chico, Calif. Difficult firefighting conditions are forecast through Friday night.

Checking in with Black voters in Georgia about the election, now that Biden is out

Some voters who could be key to deciding who wins Georgia. What do they think about Vice President Harris becoming the frontrunner in the race to be the Democratic nominee?

Tahiti’s waves are a matter of ‘life and death’ for surfing Olympics

Tahiti's Teahupo'o wave has a slew of riders for the Paris 2024 Olympics. NPR finds out why it's called one of the most dangerous waves.

Researchers are revising botanical names to address troubling connotations

Since the mid-1700s, researchers have classified life with scientific names. But some of them have problematic histories and connotations. The botanical community is trying to tackle this issue.

A spectacular opening ceremony wowed a global audience despite Paris’ on-and-off rain

The Paris Olympics opening ceremony wowed Parisians, fans and most everyone who was able to catch a glimpse of thousands of athletes floating down the Seine to officially begin the Games.