Birmingham Museum Of Art To Return Artwork To Native American Tribes

Small wooden “Aleut style” dance hat with a pattern called Tsaa Yaa Ayáanasnakh Kéet (Killerwhale-Chasing-A-Seal) carved on it. One of three objects being returned to the Native American tribes.

For the first time, the Birmingham Museum of Art will return objects from its collection to two Native American tribes. The move falls under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act or NAGPRA. The law, passed in 1990, provides a pathway for federally recognized tribes to request certain cultural items. While the process is not always drawn out, the repatriation of objects from the BMA represents years of extensive work.

“It was long for me because it took me a long time to understand where my responsibility lay,” said Emily Hanna, the museum’s Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and senior curator.

Those works will be sent to the Central Council Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska later this summer. But not all works sought for repatriation are returned. There’s a lot of research involved to determine rightful ownership.

“I didn’t want to get it wrong on behalf of the museum. I had to do my due diligence and do the research,” Hanna said.

The first letter of interest came from the tribes in 2007. To comply with the NAGRPA, the museum consulted with the tribe, answered questions regarding the objects requested and looked into their provenance or origin.

After nearly a decade of corresponding with representatives of the tribes, a delegation of six people visited the museum in 2017.

“We opened all the cases, we brought things up from storage and it was the most moving experience to be with this group of tribal members as they were telling stories and having memories about particular objects,” Hanna said.

The group requested six objects. Hanna said three had everything in the claim needed to justify the return of those works to the tribes.

The BMA will repatriate a large sculpted wooden whale fin that would have been part of a house. Hanna said it was not individually owned but rather owned by a clan. It could not have left the tribe by means of any one individual.

“They remembered it [the artwork] and made a very clear case for its return,” Hanna said.

The museum will also repatriate a staff, which was associated with a burial, as well as a hat that has a scene of a killer whale chasing a seal.

The objects being repatriated: A wooden “Aleut style” dance hat with a pattern called Tsaa Yaa Ayáanasnakh Kéet (Killerwhale-Chasing-A-Seal) carved on it (bottom left), a cane which was taken from a grave (right), and a finial known as Kéet Koowaal (Killerwhale With a Hole In Its Fin) belonging to the Kayáashkéedítaan clan of the Shx’at Khwaan, the “Wrangell People”(top left).

The whale fin will go back to a community in Wrangell, Alaska. She said members of the tribes have been forthcoming in sharing information about where the objects will go but they don’t have to.

“Once we repatriate to the central council, which is the tribal representative, then it’s at their discretion to share the whereabouts of the objects because they are representing individuals and clans.”

After the repatriation is complete, the BMA will no longer have ties to the artwork. She said the relationship between art museums and Indigenous tribal nations is changing in many important ways, but there is still a long way to go.

“I think that particularly for people who are trained in art history and trained for art museums, they haven’t been properly trained to comply with NAGPRA. They don’t really understand the legislation,” Hanna said.

Representatives from the BMA will travel to Alaska to attend the repatriation ceremony this fall.

Editor’s Note: The Birmingham Museum of Art is a program sponsor of WBHM, but the news and business departments operate separately.

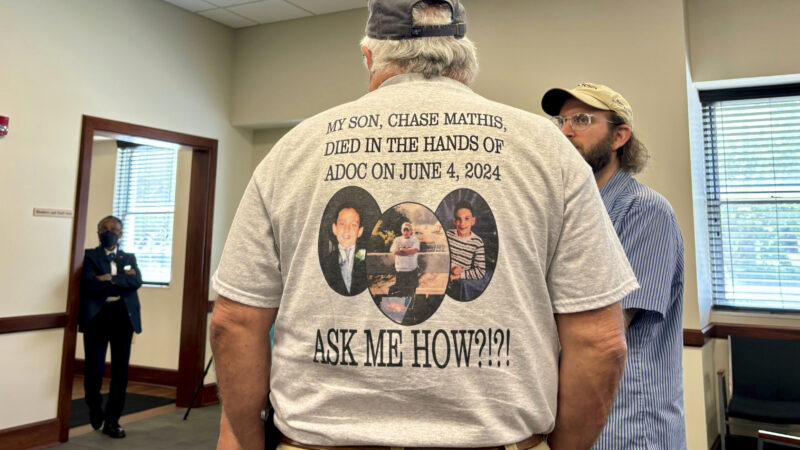

Alabama prison chief responds to families’ criticism

The department said that a number of changes have been made since Corrections Commissioner John Q. Hamm was appointed in 2022. The department said hiring has increased, and there are ongoing efforts to curb the flow of contraband and improve communications with families.

40 years after ‘Purple Rain,’ Prince’s band remembers how the movie came together

Before social media, the film Purple Rain gave audiences a peak into Prince’s musical life. Band members say the true genesis of the title song was much less combative than the version presented in the film.

Park Fire in California could continue growing exponentially, Cal Fire officer says

Cal Fire has confirmed that over a hundred structures have been damaged in the Park Fire, which grew overnight near Chico, Calif. Difficult firefighting conditions are forecast through Friday night.

Checking in with Black voters in Georgia about the election, now that Biden is out

Some voters who could be key to deciding who wins Georgia. What do they think about Vice President Harris becoming the frontrunner in the race to be the Democratic nominee?

Tahiti’s waves are a matter of ‘life and death’ for surfing Olympics

Tahiti's Teahupo'o wave has a slew of riders for the Paris 2024 Olympics. NPR finds out why it's called one of the most dangerous waves.

Researchers are revising botanical names to address troubling connotations

Since the mid-1700s, researchers have classified life with scientific names. But some of them have problematic histories and connotations. The botanical community is trying to tackle this issue.