Many Alabama Legislators Use Private Email, Limiting Public Access

The controversy continues over Hillary Clinton’s use of personal emails during her tenure as secretary of state, and it’s raising broader questions about how public officials should communicate electronically. In one survey, 33 percent of government workers said they use personal email for government business at least sometimes. The issue? Private emails are nearly impossible for the public to access.

If you thought AOL and Hotmail were dead, just scroll down the list of Alabama lawmakers and check out their contact info. State senators and representatives also list plenty of Gmail, Yahoo and emails tied to their personal websites. In Alabama, more than half the state’s House members and almost a third of senators use an email other than the state-issued .gov email address.

Among them is Representative Tim Wadsworth. He pulls out an iPad and an iPhone, where he gets emails and texts.

“First one says, ‘Hi Rep Wadsworth, I’m a reporter on an assignment, and need some info.’ And I think at 10:38 a.m. you sent me a message,” says Wadsworth as he scrolls through his emails.

“Let’s see. I think, within a few minutes, I called you right back.”

A few hours later, we’re sitting across from each other at a Starbucks. And this, he says, is why he sticks with his personal email—so people can have quick, easy access to him.

“I use my email a lot, and I don’t want to be in a situation where I’m using my government email address for any type of personal business,” he explains. “So, I just use everything on my personal.”

Wadsworth, like all of his colleagues in the Capitol, has a state-issued email address—the one that ends with .gov. But for him and many others, it’s almost like a dummy email. In other words, they don’t use it. Wadsworth says with the .gov address, he’s afraid he might not get emails as quickly.

But Dan Bevarly, interim executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, says there’s a problem with using non-governmental emails to conduct public business.

“What we found in many cases is that it is used to conduct public business, but to do so in private,” says Bevarly.

State prosecutors are using emails as evidence in an ongoing corruption case against House Speaker Mike Hubbard. Last month the Chicago Tribune sued Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel for access to private emails about city business. Bevarly says getting emails from a third party can be a long process.

“Not only does it take time, it also takes money. Time is money,” says Bevarly, potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees. If a public official fights a records request, those legal fees are often on the taxpayer’s dime.

Bevarly says public officials could just delete messages. Whereas with a .gov email address, those messages would still be available on a government server.

In Alabama, official emails are permanently kept on servers at the Alabama Supercomputer Authority.

To be clear, whether it’s a government or a personal email, every exchange is a public record. Bevarly says using a personal email makes things less transparent.

But not all lawmakers see it that way. House Representative David Faulkner says comparing state lawmakers using private emails to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is ridiculous.

“I can’t even fathom the link between the two,” he says, adding that state legislators are totally different.

“We don’t have national secrets. We don’t have protected information that’s, you know, classified,” says Faulkner.

Alabama Press Association general counsel Dennis Bailey says he gets that distinction, but stresses the emails of public officials are still government records.

“Alabama has open records laws and it has laws regarding the maintenance and protection of state records, and those laws apply to state legislators,” says Bailey.

Bailey says if people want transparent government—to see why legislators do what they do— they’ve got to have access to emails.

“That’s where the communication on a lot of very important issues is conducted,” Bailey says.

So important, prosecutors presented some of Alabama House Speaker Mike Hubbard’s emails as evidence last month, including conversations with former Governor Bob Riley. They plan to show how Hubbard used his office for personal gain.

Florida’s 6-week abortion ban will have a ‘snowball effect’ on residents across the South

Abortion rights advocates say the ban will likely force many to travel farther for abortion care and endure pregnancy and childbirth against their will.

Attitudes among Alabama lawmakers softening on Medicaid expansion

Alabama is one of ten states which has not expanded Medicaid. Republican leaders have pushed back against the idea for years.

Birmingham is 3rd worst in the Southeast for ozone pollution, new report says

The American Lung Association's "State of the Air" report shows some metro areas in the Gulf States continue to have poor air quality.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

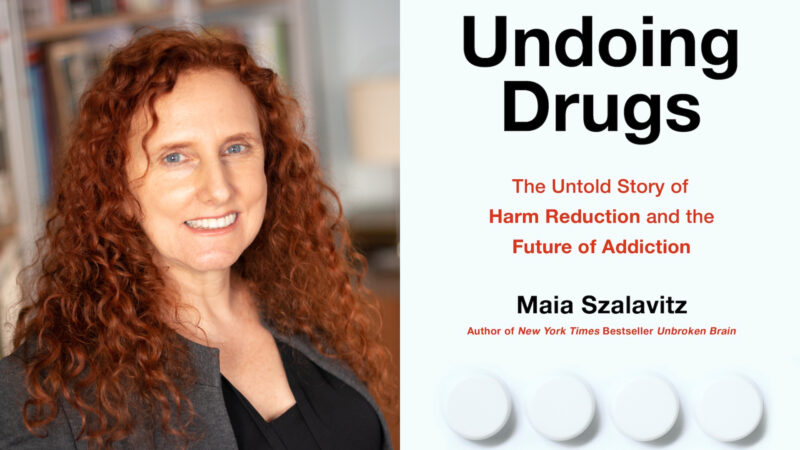

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.