Emmett Till is being memorialized with 3 national monuments. Here’s where they’ll be located

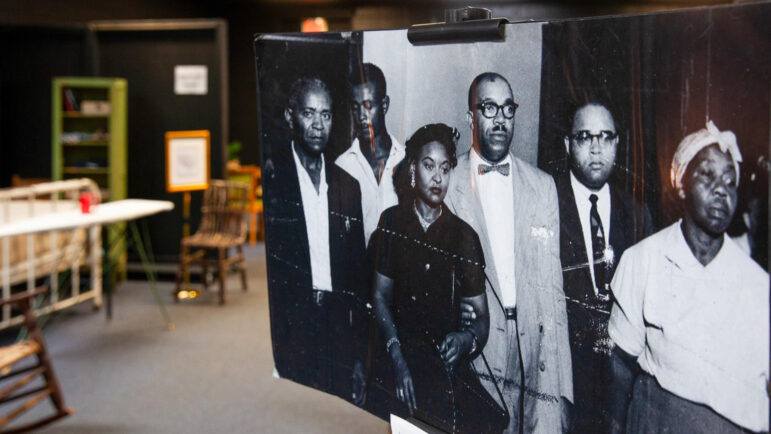

Emmett Till Interpretive Center Education Director Benjamin Saulsberry and National Parks Conservation Association Senior Director of Cultural Resources Alan Spears stand on the banks of the Tallahatchie River — the approximate location of where 14-year-old Emmett Till’s body was found, on Wednesday, July 19, 2023, in Mississippi. Till was a Black teen kidnapped, tortured and killed by two white men in Mississippi in 1955.

Today, July 25, would have been Emmett Till’s 82nd birthday.

Instead, the 14-year-old Black teen from Chicago was kidnapped, tortured and killed by two white men in Drew, Mississippi, in August 1955 after he was accused of whistling at a white woman, Carolyn Bryant Donham, while on vacation visiting family.

His death, and his mother’s response to it, helped launch the civil rights movement. Now, President Joe Biden is expected to sign a proclamation establishing a new national monument preserving three sites — two in Mississippi and one in Illinois — where Till’s life began and ended.

Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ Bronzeville, a historically Black neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, is one of the three sites. Thousands of people gathered at the church to mourn the teen after Mamie Till-Mobley decided to hold an open-casket funeral in September 1955 — revealing how badly her son had been mutilated.

Graball Landing, on the banks of the Tallahatchie River in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, is the first of two Mississippi sites being recognized. The spot is a “well-accepted” approximation of where Till’s body was recovered, Benjamin Saulsberry, education director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, said.

Till was kidnapped by Roy Bryant, Bryant Donham’s husband at the time, and J.W. Milam after Bryant Donham said the teen whistled at her in her family’s grocery store. After kidnapping Till, the pair tortured him before shooting him, then weighted his body and tossed him into the river.

The landing is in a deeply rural area, down a gravel road that winds through miles of corn and soy. A large bulletproof sign is the only indication that something happened here.

“I think it’s through the recognition of these spaces, like this one especially that speaks to us,” Saulsberry said. “To be able to acknowledge for better, for worse or otherwise, the truths of how this nation has gotten to where it has gotten and then to say objectively, we have to do differently and better.”

Saulsberry said a national monument could encourage visitors to think more critically about the role they have in dismantling racist systems.

“My hope is 70 years down the road, you know, we can ask ourselves, why were we so little?” he said. “Why were we so small in our thinking and our valuing of one another? Why are we so willing to take for granted the brevity of life? And as such, why would we allow for an environment in a system that would perpetuate or sometimes reward the dehumanization of people?”

The third site is in nearby Sumner, Mississippi, at the Tallahatchie County Courthouse where the two men accused of killing Till were put on trial in September 1955 — just a week or two after Mamie Till-Mobley held Till’s open casket funeral.

Because of that funeral, national attention turned to Mississippi. The modest courthouse would have been “packed to the gills,” Alan Spears, senior director of cultural resources for the National Parks Conservation Association, said.

Here, an all-white, all-male jury acquitted the two men who murdered Till after just five days at trial. The two later confessed to the crime, but nothing ever happened to them. Bryant Donham also testified at the trial that Till touched her and made sexual statements — though she admitted to lying about some of the details.

Spears believes the national park designation provides a bit of narrative justice for Till, something he and many others who were met with unjust violence, weren’t afforded while they were alive.

“We say their names to make sure that we honor their lives and that we remember them, and as long as their names are spoken, they will never be forgotten,” Spears said. “We do that by saying Emmett’s name and by saying Mamie’s and by remembering. That gets us there. It doesn’t get us all the way, but it gets us there, or at least a little bit closer.”

Gulf States Newsroom deputy editor Rashah McChesney and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Park Fire in California could continue growing exponentially, Cal Fire officer says

Cal Fire has confirmed that over a hundred structures have been damaged in the Park Fire, which grew overnight near Chico, Calif. Difficult firefighting conditions are forecast through Friday night.

Checking in with Black voters in Georgia about the election, now that Biden is out

Some voters who could be key to deciding who wins Georgia. What do they think about Vice President Harris becoming the frontrunner in the race to be the Democratic nominee?

Tahiti’s waves are a matter of ‘life and death’ for surfing Olympics

Tahiti's Teahupo'o wave has a slew of riders for the Paris 2024 Olympics. NPR finds out why it's called one of the most dangerous waves.

Researchers are revising botanical names to address troubling connotations

Since the mid-1700s, researchers have classified life with scientific names. But some of them have problematic histories and connotations. The botanical community is trying to tackle this issue.

A spectacular opening ceremony wowed a global audience despite Paris’ on-and-off rain

The Paris Olympics opening ceremony wowed Parisians, fans and most everyone who was able to catch a glimpse of thousands of athletes floating down the Seine to officially begin the Games.

Kamala Harris faces racism and sexism as she moves closer to presidential nomination

As Vice President Kamala Harris ramps up her campaign for president, Republicans are trying out new — and old — attacks focused on her race and gender, including calling her a "DEI candidate."