Advocates warn of a ‘dollar store invasion.’ Researchers are still figuring out the consequences

Trash, including an overturned grill, litter the outskirts of a Family Dollar parking lot in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Editor’s Note: This is Part 2 of a three-part series examining the rapid expansion of dollar stores in the Gulf South region and the consequences of it. You can read other entries in the series here:

- Part 1: Dollar stores are everywhere in the South. These 5 charts explain what’s behind their growth

- Part 3: With ‘dollar stores in every direction,’ some communities are saying enough

Forcing out mom-and-pop stores. Providing fewer jobs while paying less. Harming public health. These are just a few problems caused by dollar stores, according to a recent report from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance.

The report presents the dollar chains as a disease spreading across America, stripping communities of wealth while offering little-to-no fresh food and giving back dangerous, low-paying jobs. Other voices have been joining the anti-dollar store crescendo, with at least 75 communities rejecting the stores since 2019.

At the same time, plenty of shoppers love dollar store brands. And when it comes to the public health and economic consequences of the chains, some researchers say there isn’t enough evidence yet to justify the villain label. Some believe the stores could even benefit rural shoppers who have few nearby alternatives for buying necessities.

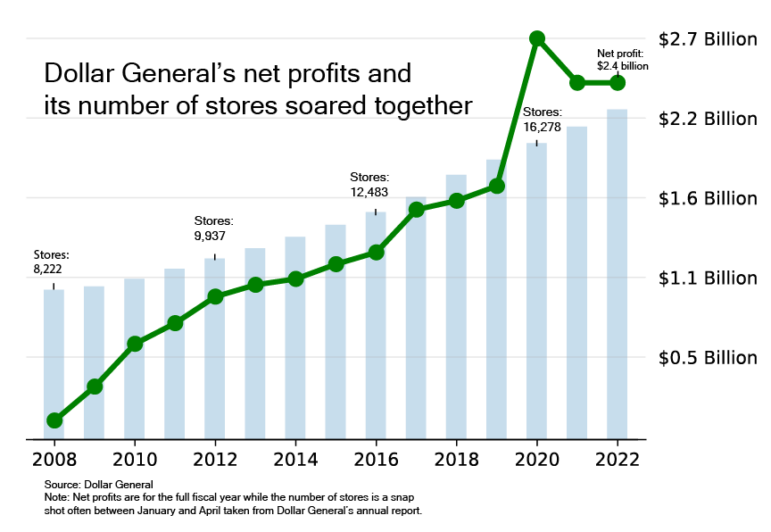

But the ILSR says waiting years for more studies isn’t an option as the rising dollar store expansion marches forward. After all, Dollar General alone opens about three stores a day.

“If we allow the dollar chains to keep multiplying at this pace, we’re going to look back in 10 years and be very sorry that we did that,” Stacy Mitchell, co-executive director of the ILSR, said.

The high cost of low prices

Plenty of worries haunt independent grocery stores, like trouble finding workers and fewer customers in shrinking small towns. Topping the fear list: Competition from dollar stores.

Rural Kansas grocery store owners labeled the dollar stores as the top challenge alongside competition from supermarkets in a 2021 survey. Some grocers said a dollar store opening nearby could cause a 20-to-30% drop in sales — a steep decline when profit margins can be as slim as 1-to-2%.

The risk of dollar chains closing grocers is about more than communities losing another business, according to Erica Blair, program manager for Kansas State University’s Rural Grocery Initiative, which conducted the survey. Grocers often act as town anchors and gathering spots. Owners invest in the community, and money spent at independent grocers circulates back through the local economy. There’s also the fresh produce that’s rare-to-nonexistent in many dollar stores.

In other words, a dollar store is no substitute for a grocer.

“They are doing all of these things that really show how much responsibility they feel to their customers and to their community,” Blair said. “That’s just not something we really hear about with dollar stores.”

The ILSR said this is not a case of dollar stores winning the free market game over grocers. Instead, the group argues dollar stores have the unfair advantage of using their market size to negotiate better deals than small businesses receive.

The report adds these companies often provide “cheater” sizes exclusively to dollar stores — products that look the same as the ones sold by grocers, just slightly smaller. For example, a Snickers at a dollar store could weigh two ounces less than those sold at a grocery store. While it might be priced cheaper at the dollar store, it might actually be more expensive per ounce. ILSR says antitrust laws need to be better enforced to prevent this.

Beyond what the stores sell inside, dollar store brands also provide fewer jobs and tax revenue, according to the ILSR. Tiny store footprints compared to dollar stores reduce property taxes and the chains get tax subsidies from some communities. Keeping prices and costs low means hiring fewer workers without as many hours.

Often, stores have just one employee punched in at a time. This type of understaffing creates the stores’ infamously messy aisles littered with unstocked merchandise boxes. But that’s more than an eyesore — it’s also dangerous. Inspectors with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration have found merchandise blocking fire extinguishers and tripping hazards regularly created by blocked aisles. For this, and other reasons, the agency has hit Dollar General for more than $15 million in fines since 2017.

Combine all of this with lax security, and it makes the stores a target for robberies, according to ProPublica.

“The dollar chains are notoriously abusive employers,” Mitchell said. “Dollar General and Dollar Tree have not invested in even basic safety features.”

Few studies on impact

Even while celebrating her new doctorate, Wenhui Feng was busy thinking about what to research next. She just received her Ph.D. in Public Administration and Policy from SUNY Albany and was on a post-grad school road trip. That’s when she noticed on the drive a dollar store followed by another one. And another one. And another.

“What’s going on?” she thought at the time. “Why am I seeing so many dollar stores?”

The number of Dollar Generals in the U.S. has nearly tripled since 2004, but when Feng got back to a computer, she was surprised to see little research into the national impact of the dollar store spread on public health. And with that, she had her new research topic.

Feng, who works as a professor at Tufts University School of Medicine, recently published a paper showing the percentage of food consumed from dollar stores almost doubled from 2008 to 2020 — but only from 1.1% to 2.1%. While it was especially high for Black Americans in rural areas, it was still under 12%.

But even the idea that more food bought from dollar stores hurts public health can’t be assumed, according to Feng. While the stores often lack fresh produce, it could be that shoppers simply shifted the unhealthy products they were already buying from grocers to dollar stores. That’s what she’s working on for a new paper.

“On one hand, dollar stores may provide easier access to some food,” Feng said. “But on the other hand, those foods may not be the most healthy. So how do people balance that out? It’s not very clear.”

Dollar General does run some DG Markets, which offer fresh produce and meat, but they make up only a small portion of its stores. The company also said it’s bringing more fresh food to its traditional stores. At the same time, Dollar Tree, which also owns the Family Dollar brand, temporarily stopped selling eggs because the currently high egg prices just don’t match the brand.

To bring together the current research on dollar stores, Feng co-hosted a dollar store conference at Tufts in June, with panels discussing everything from nutrition to regulation. About 60 attendees from Florida to Toronto came and spoke, including Lauren Chenarides, an assistant professor at Arizona State University’s Morrison School of Agribusiness.

Chenarides was shocked to see all the criticism in the media against the dollar chains. Just as Feng had found little research into the national public health consequences, Chenarides said studies into economic repercussions of the discount chains’ spread are just starting — noting that the studies out tend to be targeted, while big papers are likely still a couple of years away.

One study involving university researchers and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service found that dollar stores operating in rural areas can make it about 8% more likely independent grocery stores will close. Sales for grocers and employment in the area can also decline.

But Chenarides says size matters — both for the type of grocer and the location. Her own research shows supermarkets in cities mostly shrug off the dollar store competition.

“Independent grocery stores in rural areas are very different than larger grocery stores in urban markets,” Chenarides said. “Anything that we can say about results from paper one versus paper two is different.”

In separate statements, Dollar General and Dollar Tree said their stores complement grocery stores in areas that have one while providing a place to shop where other stores won’t go.

“Our stores complement grocery stores and bring economic development to communities we enter, including helping to alleviate the effects of ‘food deserts’ by helping serve those who are otherwise limited in access to basic food items we provide,” a Dollar Tree representative said in an email.

Grocers in rural areas also have plenty of problems besides dollar stores, like shrinking populations leaving fewer shoppers to keep them afloat. Chenarides’ research found dollar stores often opened up in areas that just became a food desert — in these cases, a low-income area where a grocer recently shuttered. The chains were also less likely to close stores inside food deserts than outside of one, implying they can survive where grocers can’t.

How many is too many?

A big question that still needs an answer is what’s the right amount of dollar stores. Chenarides doubts one Family Dollar will alter a neighborhood. But how many stores does it take before they start crowding out the competition?

“It’s not just one dollar store — it’s the density of dollar stores,” Chenarides said.

The ILSR argues we’ve already passed the threshold of too many stores and that there’s plenty of research out there to support their warnings on the problems with the chains. A paper from 2021 found dollar stores often replaced small grocers. Another, from 2022, said the chains’ expansions led to a “large decline in the number of grocery stores.”

Chenarides’ own research showed a new supermarket is less likely to open in a food desert after a dollar store opens. ILSR acknowledges that confirming a link between the dollar brands reducing public health takes expensive and lengthy studies, but added there’s plenty of evidence the stores exacerbate poverty which, in turn, worsens diets.

At the 2022 dollar store conference, Feng’s big takeaway wasn't about health or economics. Instead, it came from a panel for community perspectives on dollar stores — and she was surprised at how much people love these brands.

“People like more options and more affordable options,” Feng said. “That is something that is very interesting to see that is supported by evidence.”

People love a bargain

Giving up the sunny beaches of South Florida to move back to Alabama’s Black Belt wasn’t a tough call for April Russell. It’s a quiet place to live, and all of her family is already here. So, she made the move last year.

And while the 2,400-person town of York doesn’t have a grocery store, she considers the place thriving because of what it does have — both a Family Dollar and a Dollar General.

“Dollar stores are the bread and butter of small towns because we don’t have Walmart here,” Russell said. “Everything you need is at the dollar store.”

In fact, Russell wishes they had three dollar stores. Part of the selling point of chains is just how many there are. That makes it easier for people without a car to get to one even in rural areas. Currently, there are about 35,000 locations for the three major dollar companies.

And while Russell would welcome a grocer, prices tend to be higher. Dollar General prides itself on keeping its prices similar to companies like Walmart.

“Sometimes the grocery stores are too expensive,” Russell said. “Dollar store you can find the same items cheaper.”

York Mayor Willie Lake said the dollar stores have their place, but he wishes they’d expand what they offer, like the fresh food and produce offered by DG Markets. Dollar stores also make it harder for his town to recruit a grocery store, but Lake said there are bigger problems preventing that.

Residents need to be willing to spend extra to support small businesses rather than drive the half-hour to the Walmart in Meridian, Mississippi. Decades of white flight has also drained York of its wealth, and the town must add more amenities, like a community center and a sports facility, Lake said.

To Lake, dollar stores are just the symptom. Getting people to move back is the solution.

“The problem is a chicken and egg. How do we get people to come back when you have little to offer?” Lake said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.