In New Orleans, a symbolic bike ride helps fight recidivism. Here’s how it impacted the riders.

Cyclists riding in the 14th annual NOLA to Angola bike ride line up in front of the steps of New Orleans Police Department headquarters, Oct. 15, 2022. The annual ride is held to raise funds for The First 72+, a local nonprofit that helps fight recidivism and supports formerly incarcerated people navigate life outside of prison.

At roughly 7 a.m. on a crisp Saturday morning in October, a crowd gathered in front of an inconspicuous house with a red door on Perdido Street in New Orleans.

The house, located almost directly behind Orleans Parish Prison, is home to The First 72+, a nonprofit named for the most critical hours for someone recently released from behind bars. Normally, the people who trickle into the house are seeking the wrap-around services that the organization provides — help with getting identification cards, jobs, food stamps and transitional housing or housing assistance.

On this day, the gatherers — 91 of them in total — were there to shred. It was the 14th annual NOLA to Angola bike ride, which highlights the 170-mile journey that many people must make from New Orleans to visit their loved ones incarcerated at the Louisiana State Penitentiary — the largest maximum security prison in the U.S. The prison is notoriously referred to as Angola because it was home to a complex of plantations by the same name before the land was used for the prison complex. Prison abolitionists argue that enslavement and the use of free labor have never ceased in this space.

Riders usually travel the whole 170-mile distance over three days — camping for two nights and ending up at the prison for the Angola Arts and Crafts Festival, which happens every Sunday along with the Angola Rodeo, in October. But after a 2-year pandemic-related hiatus from group rides — cyclists participated in 2020 and 2021 by riding solo and logging 170 miles throughout the month of October — organizers thought it best to cap the journey at 55 miles — ending at the St. James Boat Club in Gramercy, Louisiana. They also offered bikers shorter distance options of 15 and 30 miles as well.

Whether in for the long haul or not, the ride was also used to raise funds to help the First 72+ fight recidivism.

“Nobody comes out of prison and wants to go back to prison. But when you can’t get some of the wrap-around services, your chances of going back to prison are great, ” Pastor Tyrone Smith, co-executive director of the nonprofit said after a press conference on the steps of the New Orleans Police Department headquarters.

By the time the riders took off, they had already raised more than $40,000. A NOLA to Angola organizer said the final tally of funds raised was more than $50,000 — well over the goal that the nonprofit had set for the event. Fundraising remains open until December 1.

“This money would help a lot of guys get that first month’s rent and that deposit and help them to get them a place to stay,” Smith said.

I pedaled along on the 55-mile trip to hear from riders and organizers about what the NOLA to Angola ride meant for them and how they viewed the experience of visiting the prison. I also learned about how one man — recently released from Angola — is working alongside The First 72+ to help get others out.

The following excerpts have been edited for clarity.

‘The wind on my face wiped [the tears] away’

“I saw it on Instagram and, because I have family members that are formerly incarcerated, it was something that touched my heart.

[It was] really interesting just driving past some of these houses and seeing their big ass pools, their American flags … and thinking about if I wanted to stop, being nervous I’d be left behind or forgotten, even though there is such a big group. Everyone, of course, is going to check in on you, but connecting that to how people in prison probably feel because of how our society works as far as transitioning back.

It’s sad. I started crying, that is for sure. The wind on my face wiped [the tears] away. I think it was really emotional for me and I’m probably still processing a lot of it as well.“

— Carly Krulee, a NOLA to Angola bike ride participant

‘One small way people can walk the walk — or in this case, bike the miles’

“I think that NOLA to Angola is one small way people can walk the walk — or in this case, bike the miles — instead of just talking the talk in terms of wanting to be in solidarity with families, wanting to demonstrate a certain level of empathy and build a certain level of really understanding another person’s experience.

I think [it] is really a small, small way that someone who says that they are either for criminal legal reform or say that they have abolitionist practices can show that they are about what they say.”

— Alexis Yeboah-Kodie, a NOLA to Angola bike ride participant

‘We appreciate that we can be in a space … for people to embrace us’

“I did 27-and-a-half years in prison. I was convicted of second-degree murder — which was really supposed to be manslaughter — but I didn’t have adequate representation at the time. Inside of prison, I learned some things and I was blessed to be able to help guys inside of prison get out of prison.

When I was inside the prison, they had attorneys coming inside there to see me. And I’m convicted of second-degree murder with a life sentence. And they were fighting hard for me to get out of prison. There were church organizations coming up there, and all these people want to see us home. I’m like, ‘Why they fighting so hard for us?’ To where I’m like, ‘Well if they fight that hard on the outside, I’m gonna be fighting just as hard on the inside, to where I got to be worthy of that fight.’ That was one of the turning points in my life.

So, that’s why I say that this journey that you are on now, it’s going to be felt in there. Somebody’s going to be inspired. When you [are] fighting for the brothers, they appreciate it. We appreciate it. We appreciate the fact that we can be in a space where people that’s doing the same thing that we [are] doing for people to embrace us and accept us. You know what I’m saying? Because now we’re able to tell our brothers, ‘Man, look they got people that’s fighting for you.’ It’s no longer hidden, it’s visible. People understand that incarceration is not the solution.”

— Everett Offray, who was formerly incarcerated at Louisiana State Penitentiary and now works in the Civil Rights Division of the Orleans Public Defenders’ office

‘All of the stuff I read [and] watched could not have prepared me for what that was like’

“Typically, Angola concludes on a Sunday in October at the Angola Arts and Crafts Festival and the Angola Rodeo. It’s one ticket. You can’t just buy a ticket to the rodeo or the festival.

I want to talk, first, about the festival because when you walk in, that’s the first part. You get to the arts and crafts festival — you don’t get to the rodeo. And what I actually saw at the festival was something beautiful. I basically saw family reunions, in a way. People were there to see their loved ones in person — some of whom were selling artwork, some of whom were selling food, and some of whom were doing other work at the festival. And so there [were] more than a few moments like joy, laughter and tenderness — similar to what you would see in a prison visitor room.

I did not know that I was going to see that, and I’m really glad I did because, to me, it showed that that festival has a lot of different meanings to a lot of different people. So sure, are there some people who are there to live out some sort of circus fantasy of Black people in chains and in cages? Yeah, there were. But there were also Black New Orleanians and people from other parts of the region who were there to see friends and family.

The rodeo is a different experience. I’ve been to rodeos. I grew up in Indiana. Yes, we have rodeos in Indiana. What happens in Angola is a blood-thirst.

They have a variety of so-called games where imprisoned people try to achieve different objectives, all while having a bull running at them full speed, goring them with their horns, throwing them in the air [and] stomping on them. And all of the stuff I read, the stuff I watched online could not have prepared me for what that was like.”

– Jarrett Drake, a NOLA to Angola bike ride organizer and doctoral student at Harvard University

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

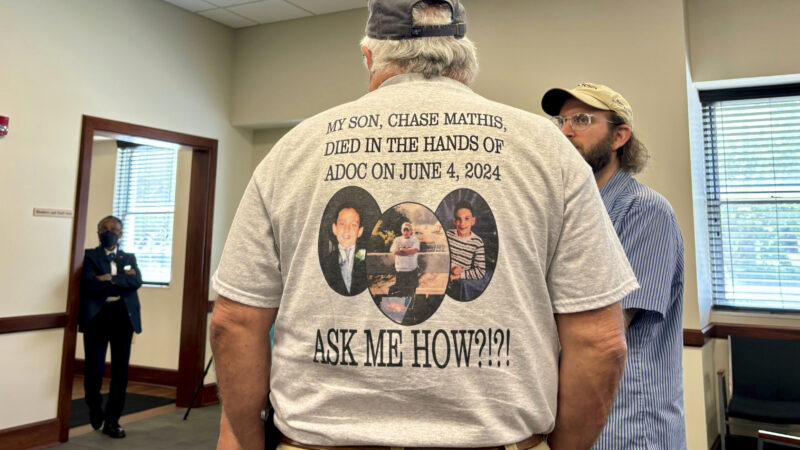

Alabama prison chief responds to families’ criticism

The department said that a number of changes have been made since Corrections Commissioner John Q. Hamm was appointed in 2022. The department said hiring has increased, and there are ongoing efforts to curb the flow of contraband and improve communications with families.

40 years after ‘Purple Rain,’ Prince’s band remembers how the movie came together

Before social media, the film Purple Rain gave audiences a peak into Prince’s musical life. Band members say the true genesis of the title song was much less combative than the version presented in the film.

Park Fire in California could continue growing exponentially, Cal Fire officer says

Cal Fire has confirmed that over a hundred structures have been damaged in the Park Fire, which grew overnight near Chico, Calif. Difficult firefighting conditions are forecast through Friday night.

Checking in with Black voters in Georgia about the election, now that Biden is out

Some voters who could be key to deciding who wins Georgia. What do they think about Vice President Harris becoming the frontrunner in the race to be the Democratic nominee?

Tahiti’s waves are a matter of ‘life and death’ for surfing Olympics

Tahiti's Teahupo'o wave has a slew of riders for the Paris 2024 Olympics. NPR finds out why it's called one of the most dangerous waves.

Researchers are revising botanical names to address troubling connotations

Since the mid-1700s, researchers have classified life with scientific names. But some of them have problematic histories and connotations. The botanical community is trying to tackle this issue.