Root Shock

Food and water. Clothing. Housing. And then, jobs and schools. As hundreds of thousands of displaced persons have moved gradually through this hierarchy of needs since the destruction caused by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, there’s a question mark that lingers, unspoken, in the background-the effect of that chaos and displacement on the evacuees’ mental health.

Psychiatrists assume that many of those individuals will suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, an illness that’s especially common among law enforcement officers, and soldiers who serve in combat. Although the New Orleans evacuees were not police officers or soldiers, many of them nonetheless witnessed grim scenes of death and violence as the floodwaters rose and living conditions deteriorated.

PTSD has a dismayingly long list of possible symptoms…of which severe anxiety, recurring nightmares, insomnia, and clinical depression are only a few. But when public health professionals search the academic literature for specific advice on helping the storm victims, they find surprisingly little information. Dr. Max Michael, dean of the UAB School of Public Health, explains why:

“I think the reason that very little research has been done in this country about resettling the population of, say, an entire city, is that displacement on this large a scale is usually caused by something man-made, like a war. And fortunately…in modern times, at least…a war has not been fought inside the United States.”

Perhaps the most relevant research about the psychological damage done to people from displaced communities is both very new, and somewhat outside the norm. A psychiatry professor at Columbia University, Dr. Mindy Fullilove, has coined a name for the phenomenon…she calls it “root shock,” which happens to be the title of her new book. For years, she’s been studying communities uprooted by a very different force: urban renewal…also known, sometimes disparagingly, as “gentrification.” Fullilove was in Alabama recently, as a consultant to the School of Public Health.

“I use the term “root shock” to mean the suffering that results from the loss of all or part of one’s emotional ecosystem. That is, the world…the intimate world…one’s neighborhood, the place where you live. It’s very common for people to suffer when they lose the world in which they were situated.”

The book’s full title is “Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It,” and it was published before the disastrous hurricanes hit. But the mental health parallels of the two types of damage are so strikingly similar that Fullilove’s research has taken on an eerie new relevance. Her path has not been an easy one. In the beginning, she says, other professionals tried to convince her that her field was not really a field at all.

“I think the idea in general, in the mental health professions, is that people have important relationships with people, and place is optional. So the idea that our relationship with place is actually a necessity…it’s not optional, you have to live someplace…flies in the face of much current orthodoxy. So we had gotten into a train of thinking about place that minimized it.”

As for the recovering hurricane victims, Fullilove believes that their most immediate mental health need is a kind of “emotional triage”.

“One of the things that has stood out with Katrina is the sense of disorientation, of not knowing what’s going on. So I would think that one of the immediate things that’s needed is some sense of grounding…whether that’s a kind of vision, or an explanation of what’s going to happen from this point forward, or just ‘What do you need, and how can we help you get it?'”

In her book, Fullilove says that even such violent dislocations can sometimes have a silver lining…a chance for people to literally start their lives over, to build a new “emotional ecosystem” that’s better suited to their needs than the old one was. But what she’s seen so far of the government’s response to the tragedy, she says, has not been encouraging.

“We don’t know how cruel our society is going to be to them. If you’re exposed to traumatic circumstances, chances are you’re going to have trauma-related mental illnesses. But if people gather around you and nourish you, and help you rebuild your house and have beautiful new furniture and get you back there, and on your feet again, you could feel pretty great. But that’s not likely. It’s likely that we will do everything bad to these people…and in that case, we can expect to see a downward spiral of problems.”

Perhaps the most damaging aspect so far for New Orleans evacuees, Fullilove says, is the ongoing talk about abandoning the city’s older neighborhoods altogether.

“The idea that maybe we will do something with the Ninth Ward that won’t include poor people in New Orleans is really an assault on somebody who has been evacuated from a disaster and then told, ‘Well, maybe you can never go home.’ That’s egregious, and very harmful to people’s mental health.”

Ironically, Fullilove says, this kind of damage is being done at a time in history when new technologies could make it easier than ever to emotionally reconnect dispersed communities.

“We have to build democratic institutions that will operate for the people in diaspora. And this should be very easy to do, using the Internet, radio, media, television…so that people feel connected to their hometowns, can have a voice through their council-people, can feel connected with their social and fraternal organizations, feel connected with their families. Short-term, you’ve got to give people the sense that they’re part of something they’ve been part of before. They have to have hope.”

Not many people fully understand, yet, just how high the stakes are, in that challenge, Fullilove says. If we fail at the task, we’re not only condemning large numbers of Americans to long-term emotional illnesses, she believes, but the ripple effect of that suffering will spread throughout society as a whole.

“Because we aren’t just people randomly scattered. We live together in neighborhoods, we work together in workplaces. And it gives us a way to see the specific relationships that we have to repair, the specific inequalities we have to abolish. The specific way of deforming American democracy that has to be abolished, because it causes this kind of pain. It’s really something that can take us in a great leap forward of being a better country. As soon as we see that, we have great hope.”

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

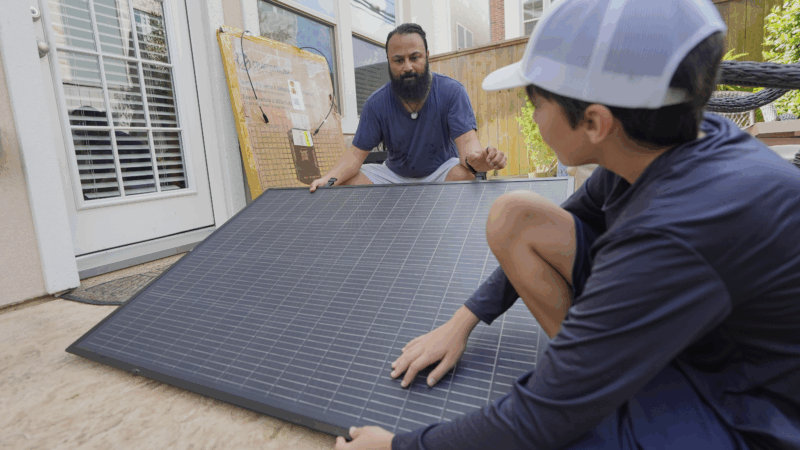

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.