No Child Left Behind

Dressed in crisp, blue and white uniforms, students at Birmingham’s Whatley school walk the hallways under the watchful eye of principal Michael Wilson. Whatley is one of 54 Birmingham area schools that didn’t make “Annual Yearly Progress” under No Child Left Behind.

“The perception is that our kids are unruly, our staff doesn’t care, and there’s not the support there. And that’s totally not true.”

In the last year, the students Whatley have made a lot of progress on standardized tests. But, the math scores for special education students missed the mark, so, the principal says, the entire school got a red flag.

“You gotta realize, I have a higher rate of special education, most urban schools do. I was looking at the percentages and I probably have 15 ? 16% overall special education population in the school. Well, that makes a huge difference in test scores!”

School system administrators across the state feeling the heat. This year, 313 Alabama schools didn’t meet their yearly progress goals. That’s almost four times the number from last year.

“It doesn’t really show the progress that our schools have made, because we have made progress.”

Eleanor Traylor oversees federal programs for Birmingham’s school district.

“For example, 73% of third graders must read at the third grade level or higher in order to meet that statistical requirement. If 72% of them read at that level, they don?t make AYP.”

If a school doesn’t make “annual yearly progress” it has to offer students transfers to higher-performing schools. But in many districts there are no other options.

“It puts me in a very bad position.”

Birmingham schools superintendent Wayman Shiver Junior says 14 of his 17 middle schools fell short.

“Right now I’m in the position of not being able to provide spaces for people who would want to transfer their children to higher performing schools.”

Almost a quarter of the schools on Alabama’s failing list are in Congressman Artur Davis’s district. Many are in Alabama’s Black Belt ? a poor, predominately African American area where there may be just one school high school in a county.

“You have this market logic brought to the school system. A market logic that says you’re all going to compete and if you don’t do well you may lose your customers. Well, if an Exxon gas station can’t compete with the BP down the road and they have to close, people just don’t go to the Exxon, they go to the BP or they drive across town. That level of easy exchange of choice doesn’t exist for our parents.”

Even when parents can transfer their students, they often choose not to. Last year, Birmingham schools had to offer 5,000 transfers. Only about 100 students took them up on it. And when those students move to higher-performing schools, the money the state allots for them also moves to the new school. That’s a major flaw in the law, says Whatley principal Michael Wilson.

“It is a civil rights issue. It is a human rights issue. And for us to say that we are equally keeping students in mind, it’s just a joke! I mean, in some ways I believe this whole No Child Left Behind is pointed at making urban and poor, rural systems look bad.”

No Child Left Behind comes up for reauthorization next year and already lawmakers from rural and urban districts are crafting ways to re-orient some federal and state funding from richer suburban school districts to struggling urban and rural ones. In Alabama, though, they concede it’s a tough political sell.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

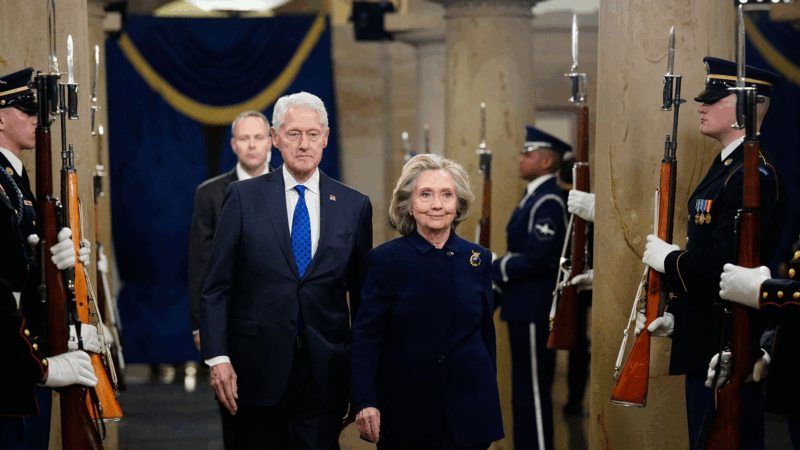

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

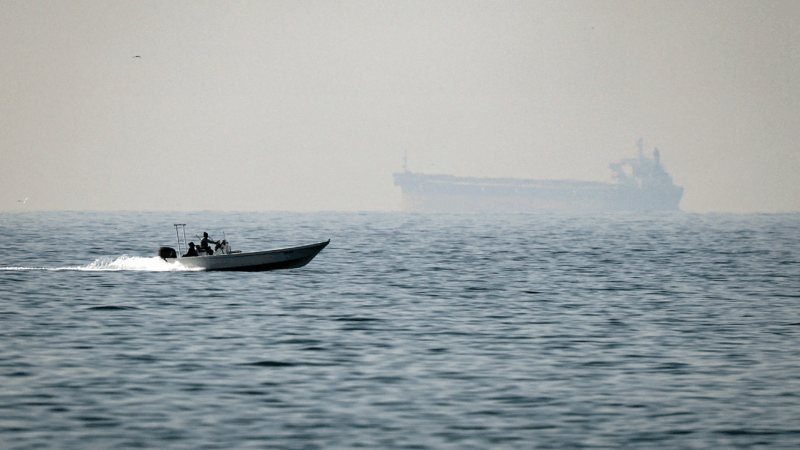

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.