When will greenhouse gas emissions finally peak? Could be soon

For almost two centuries, greenhouse gas emissions have climbed steadily as humans have burned increasing amounts of oil, gas and coal. Now, climate scientists believe those emissions may finally be reaching a peak.

Thanks to the rapid growth of renewable energy, global emissions from fossil fuels could soon start to decline. The long-awaited peak is a key milestone in the effort to limit how hot the planet will get. Studies show emissions must peak and then rapidly decline to limit impacts like more intense heat waves and storms.

Many climate researchers speculated that annual emissions could fall in 2024, indicating global emissions had already peaked. But a new study finds emissions from burning fossil fuels are still likely to increase slightly this year, driven by growing demand for electricity.

Global leaders are currently discussing efforts to cut emissions at the COP29 climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan. Despite countries’ pledges to transition away from fossil fuels, global emissions have risen almost every year since the talks began. A decline in emissions could be a sign the negotiations are finally having an effect.

Even when emissions start to fall, the Earth will still be on track for extreme impacts from climate change. Any added greenhouse gases will keep warming the planet. Emissions would need to be cut roughly in half by 2035 to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the key benchmark countries agreed to pursue in climate negotiations.

“We know that peaking is the start of the journey,” says Neil Grant, a senior climate and energy analyst at Climate Analytics, a climate think tank.

“But peaking emissions would be a real sign of human agency. If we could say: look, we can turn the corner, that would highlight to me that we do have power and so it would be a hopeful thing for me.”

Good news and bad news

The boom in renewable energy has largely been the result of economics: it’s now generally cheaper to build a new solar project than a power plant that runs on coal or natural gas. Last year, countries deployed almost twice as much renewable energy capacity as the year before. China is leading the charge, accounting for around 60% of the new renewable energy capacity added worldwide in 2023.

Loading…

The growing supply of solar and wind energy has begun to displace fossil fuels, but so far in 2024, it’s been counteracted by a growing need for electricity. Economies are growing and airline and shipping traffic is on the rise. The increased use of artificial intelligence also requires intensive amounts of electricity to run data centers. Severe heat waves around the globe this year also raised the demand for air conditioning, a sign of how worsening climate impacts can make it even harder to cut emissions.

Much of this growing energy demand is being met with oil and natural gas. That means fossil fuel emissions are not yet dropping, despite the major expansion in renewable energy. As a result, global emissions are expected to rise by 0.8% in 2024, according to the Global Carbon Budget.

“Bad news: we are not declining yet,” says Pierre Friedlingstein, one of the authors of the report and a professor at the University of Exeter.

“Good news: the growth rate is much lower than it was 10 years ago.”

Emissions in the U.S. and the European Union have been declining for years, as those countries have shifted away from burning coal. In India, emissions are expected to grow by 4.6% this year, as the country industrializes and a growing middle class uses more energy. In China, emissions are expected to increase by only 0.2%, leading some to speculate the country’s emissions will soon peak, ahead of the government’s 2030 goal.

Peaking is only the beginning

While a peak in global emissions from burning fossil fuels may only be a few years away, it doesn’t mean global temperatures will start falling. Countries will continue to add greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere, just at a slower rate. Those emissions will keep raising global temperatures. To stop temperatures from rising, greenhouse gas emissions need to fall to zero.

“At this point of peaking, your emissions are at the all-time high,” Grant says. “That means that you’re actually doing the most damage possible to the climate system per year. And so what matters most is how quickly you can get out of that high-damage zone.”

It’s like driving a car at dangerous speeds, Friedlingstein says. Hitting peak emissions is like taking your foot off the gas pedal.

“You still have to brake if you want to stop at some point, because there is a wall there and you’re driving toward the wall,” Friedlingstein says. “If you want to stop before the wall, you have to start braking.”

At the COP29 climate summit, countries are negotiating new pledges to cut future emissions, in the hope of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100. Beyond that level, the world could see much more destructive storms and floods, as well as irreversible damage to ecosystems like coral reefs. Reaching that goal would require cutting emissions to zero by 2050, though countries’ current pledges fall well short of that goal.

Still, a peak in emissions would mark an important turning point in global negotiations.

“We are still, to some extent, masters of our fates and we can control how much warming there is,” Grant says.

Review by Senate Democrats finds more unreported luxury trips by Clarence Thomas

A report by Democrats on the Judiciary Committee found additional travel taken in 2021 by Thomas but not reported on his annual financial disclosure, including trips on private jets and a yacht trip.

Where did Barry Jenkins feel safe as a kid? Atop a tree

Director Barry Jenkins is best known for films like "Moonlight" and "If Beale Street Could Talk." On Wild Card, he opens up about where he felt the safest as a kid.

Israeli strikes across Gaza kill at least 20, including five children

Israeli strikes across the Gaza Strip overnight and into Sunday killed at least 20 people, including five children, Palestinian medical officials said.

I discovered one way to fight loneliness: The Germans call it a Stammtisch

Modern life can be lonely. Some are looking to an old German tradition – of drinking and conversation – to deepen connection through regular meetups.

This Christmas I’ll be grieving. Here’s how I’ll be finding joy.

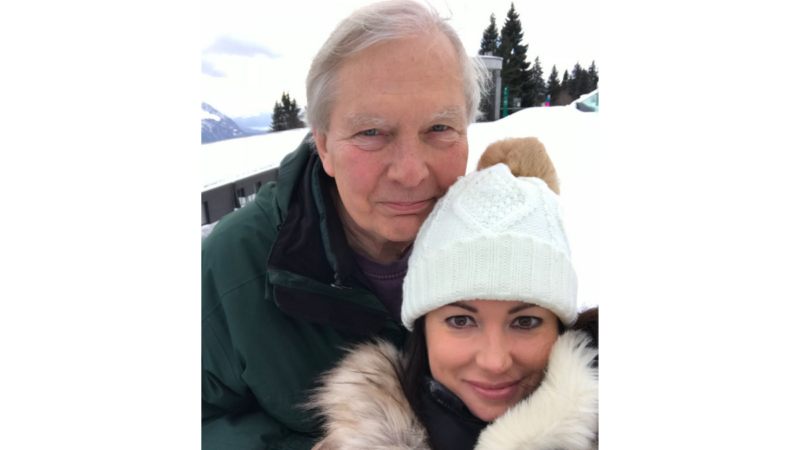

Since her husband's death, newscaster Windsor Johnston has been looking for ways to recapture joy and continue her healing journey — one that's taken her to a place she'd never expected.

On tap for the holidays: A blend of multicultural drink traditions and fond memories

For this year's All Things Considered holiday cocktail interview, we visited Providencia in Washington, D.C., a bar that brings its owners' personal stories to life.