Voices from the new breadlines in Syria: Who’s waiting? And why?

DAMASCUS, Syria – There are separate lines for men and women outside a Damascus bakery – it’s not polite in this city for men and women to squish against each other. And there are so many people here, waiting for bread, that they’ve parted into gender-segregated queues.

The wait is long, and the bread they’re hoping to buy costs up to ten times more than it did just weeks ago — from 400 Syrian lira to 4,000 Syrian lira for a dozen pieces of dinner-plate sized flat bread. That new price is the equivalent of 31 cents.

Rahaf, 35, mother to eight children, says she’s barely scraping by. “I’m only alive because I’m not dead,” she says.

Like many other Syrians NPR interviewed for this story, she only gave her first name. Others asked not to be named at all. That’s because they were worried that talking about the bread crisis could get them into trouble with the interim government.

The bakery scene, post-Assad

There have been scenes like this across the Syrian capital’s 69 bakeries since rebels toppled the Assad regime and formed a new interim government in early December.

“We’re in a period of some chaos,” says Joshua Landis, a Syria specialist, co-director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma. Bread is politically sensitive in Syria as it is across the Middle East, where its price and availability have triggered protests in the past.

Syria’s old Assad regime heavily subsidized bread, Landis says. But it often wasn’t available – one of the reasons why Assad was toppled – along with soldiers abandoning their posts and the weakening of their allies Hezbollah and Russia.

(Ayman Oghanna for NPR)

Landis says if this new regime can’t resolve the bread crisis, it will soon become a political crisis as well as a hunger crisis. “It’s very hard for us to understand the level of need. The vast majority of Syrians,” says Landis, “they’re just barely subsisting.” Just a few months ago, the U.N. reported that 90% of Syrians were living below the poverty line.

The illegal sale of bread adds to the frustrations. Mohammad Siyadeh, of the Ministry of Supply, which oversees the purchase of flour, says the old subsidized price of 400 Syrian lira, or 3 cents, for 12 pieces of flatbread, encouraged bakeries to sell bread on the black market for a steep profit.

“We found a lot of corruption,” Siyadeh says. He says by raising the price to 4,000 lira, the bakeries are less likely to sell to the black market. The new pricing, he says, prevents 765,000 tons of flour from being leaked onto the private market each day.

Even with the price hike, he says the ministry is still subsidizing bread, which he says would otherwise cost 12,000 Syrian lira, or 92 cents, for a dozen pieces. Most Syrians live on less than 2 dollars a day.

Siyadeh acknowledges that these higher prices have caused hardships. On Jan. 6, the government announced that public sector pay would be increased fourfold, which he hopes will ease conditions for many families.

The black market in bread persists

But some bakeries are still selling bread on the black market, one bakery worker tells NPR.

“The subsidies that the government provides isn’t enough to cover costs,” said a bakery worker. “If we don’t sell privately, we’d be making a loss every day.” And they’re able to charge higher prices to these black market buyers (who then sell the bread at even higher prices).

On a January day, NPR saw dozens of people in a breadline — competing with cars that would slow down as they neared the window counter, which overlooks a sidewalk. Bakers hurriedly handed over plastic bags that appeared to contain dozens of pieces of flatbread, presumably to be sold on the black market. Every one of those exchanges – there were at least half a dozen in the hour that NPR was there — slowed down the bakers’ ability to service the lines of people, resulting in longer waits for bread to be prepared.

“The subsidies that the government provides isn’t enough to cover costs,” said a bakery worker. “If we don’t sell privately, we’d be making a loss every day.”

And it’s not just the drive-by buyers who are part of the black market scene. Impoverished Syrians are packing the lines, buying as much bread as possible, then reselling it on the roadsides. The government tolerates those sales, Siyadeh says, because they’re one of the few reliable ways poor Syrians can make any money. “I have to sell bread to feed my children bread,” says 65-year-old Khalaf, who was selling two dozen pieces of flat bread by a roadside.

One black market customer is a 33-year-old single mother of three children, who had just purchased a dozen pieces from a roadside seller at a markup of 16 cents — paying 47 cents in total. She tells NPR she’s got kids at home and can’t waste time standing in a line. Even so, she was borrowing money for food. “Neighbors help me, they understand my situation.”

Despite the new higher bread prices, she says the current government is better than the Assad regime, which detained her husband — never to return. “That freedom is more important than bread,” she says.

Running low on flour

But there is a far more serious problem looming on the horizon. Siyadeh, of the ministry of supply, says the country has only a five-month supply of flour in storage. That’s it.

Russia, a close ally of the former Assad regime, used to supply Syria’s flour. But Russia halted those supplies after the new government took power, ostensibly over concerns about payment.

One country has offered help: Ukraine — another of the world’s great wheat producers, which is repelling a Russian invasion of its territory. In a December visit to Damascus, Ukraine’s foreign minister, Andrii Sybiha announced a gift of 500 tons of flour and said his country was ready to offer more.

Siyadeh says his country would like to purchase flour from Ukraine, but there’s a problem. “The sanctions on Syria,” he says. “They are the biggest problem facing us in terms of importing wheat.”

U.S. and European sanctions were largely imposed to punish the former Assad regime for its violent crackdown on Syrians. They’ve remained in place even after rebels toppled the Assad regime and largely prevent the Syrian government from using the international banking system, which is crucial for purchasing imports like flour.

On Monday, the U.S. State Department announced it would make it easier for the new government to purchase humanitarian aid but kept sanctions in place. But “so far, we haven’t seen any impact,” Siyadeh says of those eased-up rules on international purchases.

The sanctions have been a matter of deep frustration for the new government. “Don’t burden us with decisions you are fixated on, that is increasing the suffering of Syrian people,” said Syria’s new ruler, Ahmad al-Sharaa to a Saudi news channel in late December. By decisions, Sharaa was referring to the West’s use of sanctions.

Outside the bakeries, some Syrians say their patience is already wearing thin. As my NPR colleague and I walk down one breadline, a retired school teacher stops me. “I’ve been waiting here for two hours,” he says. “Until when? This new regime told us it’s bringing freedom,” he says, shaking his head. “But we can’t buy bread.”

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

It’s been weeks since rebels toppled the Assad regime in Syria and formed a new interim government. That government is already facing a serious challenge – bread lines, as NPR’s Diaa Hadid reports from Damascus. Before we begin, please note that some Syrians interviewed for this story only gave their first names or asked not to be named at all. That’s because they were worried their words could get them in trouble with the new interim government.

(SOUNDBITE OF MACHINERY RUNNING)

DIAA HADID, BYLINE: There’s a line for men and another for women outside this bakery that pumps out industrial quantities of bread. Each line has dozens of people, and the bread they’re hoping to buy costs up to 10 times more than it did under the old Assad regime.

(SOUNDBITE OF BREAD FALLING ON COUNTER)

HADID: The dinner-plate-size pieces of flatbread thump off a conveyor belt onto a table near the counter.

(SOUNDBITE OF BREAD FALLING ON COUNTER)

HADID: One woman hands over money for 48 pieces. It’s just a few days’ supply for most Syrian families in a country where bread is the staple.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: (Singing in non-English language).

HADID: There are scenes like this across Damascus. At another bakery, 35-year-old Rahaf, mother to eight, jokes to me that she’s only alive because she’s not dead.

RAHAF: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: Rahaf, like all the other Syrians I hear from, didn’t want to give her full name. They fear reprisals because they’re talking about a sensitive topic.

JOSHUA LANDIS: Those bread lines are telling you a story about Syria today, why this Assad government fell and the challenges that face this new regime.

HADID: Joshua Landis is a Syria specialist at the University of Oklahoma. He says bread is so politically sensitive in Syria that the Assad regime heavily subsidized it, but it often wasn’t available. Landis says that’s partly why Assad was toppled. And if this government can’t resolve the bread crisis, it will become both a hunger crisis and a political one.

LANDIS: It’s very hard for us to understand how most Syrians are surviving. They’re just barely subsisting.

HADID: Like Noor. He’s 21, but looks 12…

NOOR: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

NOOR: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: …Thin, short, gaunt. He’s dreamily chewing on a scrap of bread. “I’m just resting for a bit,” he says.

NOOR: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: “I waited for an hour in line for this.”

The bread lines and the prices are sensitive for the new regime. I see two men approach Noor.

NOOR: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: Later, he tells me they’ve told him not to talk. These bread lines have created their own industry. Poor folks buy up the bread and resell it by the roadside. Among them is 12-year-old Mohammad, whose back aches from standing in line all day.

MOHAMMAD: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: He resells the bread to people like this 33-year-old single mother. She’s got young kids at home, and she can’t waste time standing in line.

UNIDENTIFIED MOTHER: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: Despite the new hardship, she says this is better than the Assad regime which detained her husband. He never returned.

UNIDENTIFIED MOTHER: (Speaking Syrian Arabic).

HADID: She says, “we’re no longer living in fear.”

She’s got faith in this government. And over the weekend, Syrian officials announced that public-sector pay would increase by four times to help alleviate the current economic crisis. Analysts say there’s a few reasons why the price of bread is increasing. As rebels seized Damascus, the Syrian currency tumbled, in turn pushing up prices. And Russia, which was a close ally of the former Assad regime, used to supply Syria’s wheat flour. Now, the Reuters news agency says Moscow’s halted supplies. But one country has offered help – Ukraine, another of the world’s great wheat producers, which also happens to be fighting against Russia.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

HADID: In a recent visit to Damascus, Ukraine’s foreign minister, Andrii Sybiha, announced a gift of 500 tons of flour. He says more’s on the way.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

ANDRII SYBIHA: (Speaking Ukrainian).

HADID: That may depend on the new Syrian government renouncing the former Assad regime’s recognition of Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian land.

(CROSSTALK)

HADID: Outside the bakeries, people are impatient. We walk down one bread line…

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: …And one man tells us to stop recording. It’s not clear who he is, but it can also be risky to ask.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: “OK, I’m done,” I tell him.

A few feet away, a retired schoolteacher stops me. He tells me, “I’ve been waiting in this line for two hours.” He says, “this regime told us it’s bringing freedom, but we can’t buy bread.”

Diaa Hadid, NPR News, Damascus.

Alex Ovechkin scores goal #895 to break Wayne Gretzky’s all-time NHL scoring record

The Washington Capitals star made history with a power play goal from the left faceoff circle — as Gretzky, who last set the record more than 25 years ago, looked on.

Severe storms and floods batter South and Midwest, as death toll rises to at least 18

Severe storms continued to pound parts of the South and Midwest, as a punishing and slow-moving storm system unleashed life-threatening flash floods and powerful tornadoes from Mississippi to Kentucky.

Israeli strikes on Gaza kill at least 32, mostly women and children

Israeli strikes on Gaza killed at least 32 people, including over a dozen women and children, local health officials said Sunday, as Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu headed to meet President Trump.

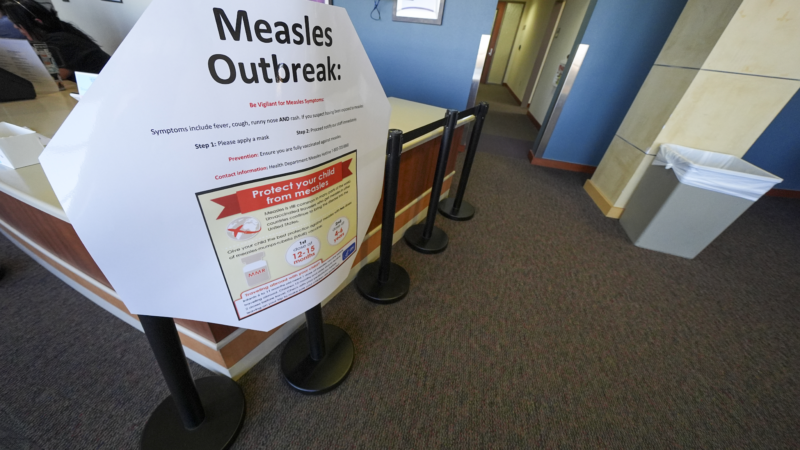

Second child dies from measles-related causes in West Texas, where cases near 500

A second school-aged child in West Texas has died from a measles-related illness, a hospital spokesman confirmed Sunday, as the outbreak continues to swell.

Yemen Houthi rebels say latest US strikes killed 2, day after Trump posted bomb video

Suspected U.S. airstrikes killed at least two people in a stronghold of Yemen's Houthi rebels, the group said Sunday.

1 killed in Russian attack on Kyiv as death toll from missile strike rises to 19

One person was killed Sunday as Russian air strikes hit the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, while the death toll from Friday's deadly attack on the central Ukrainian city of Kryvyi Rih continued to rise.