Ukrainian soldiers and shopkeepers hold on as Russia’s siege of Pokrovsk tightens

POKROVSK, Ukraine — In the final hours of 2024, the embattled Ukrainian city of Pokrovsk suddenly went dark. Its electric grid, long battered by Russian drones and artillery, failed on Monday for what the city’s military administration said would be the last time.

“The past year has been extremely difficult,” local officials said in a post on the Telegram messaging app. “We started 2024 with hope but the community has faced large-scale destruction.”

Already thousands of civilian residents, believed by officials to still be hanging on in Pokrovsk, were enduring the winter and the war without running water. Gas pipelines used to heat homes and businesses have also been shut down.

In public statements, Ukraine’s general military staff says Russia’s most intense ground assaults along the entire eastern front are currently taking place in the Pokrovsk region, with between 30 and 60 attacks each day, some within a mile of the city.

Despite the brutal conditions, during a recent visit to Pokrovsk, NPR found Svitlana Storozhko still operating a small grocery store and café. “Grandma, take this, it’s extra,” she said to an elderly woman making a purchase as the thunder of artillery echoed in the empty streets outside.

“There will be bread tomorrow,” Storozhko promised.

“What about the sausage, is that fresh?” asked the customer, in an exchange that sounded eerily normal.

“It’s fresh, don’t worry, you’ll see, you’ll come back again,” said Storozhko.

Asked why she hadn’t yet evacuated, the shopkeeper laughed and confessed she had already sent her pets to live with friends in a safer community away from the front lines. But she had decided to stick it out a little longer.

“We believe in God and in Ukraine’s armed forces,” Storozhko said with a shrug.

But remaining in Pokrovsk is an increasingly perilous choice. “There are already battles on the outskirts,” said Vasyl Pipa, 41. He’s acting head of an evacuation team made up of police officers from around Ukraine, known as the White Angels, that helps civilians leave the Pokrovsk military district.

According to Pipa, it’s often difficult to convince Ukrainian families to leave even when the war is at their doorstep.

“There are families who have come back to the city even with children and it’s devastating,” he said. “We try to be like psychologists, not putting pressure on them, but staying near and helping them [make the decision to go].”

Asked about the danger his own team faces in Pokrovsk, Pipa said it’s hard after nearly three years of war to remember what safety and normal conditions feel like. “Our way of thinking about danger, the proper limits of danger, have moved and shifted and changed,” he said.

A coal mining town, a siege, thousands dead

The Russian government has long seen this hardscrabble industrial town as a strategic prize. Pokrovsk’s mines produce coal that’s vital to Ukraine’s steel industry. Rail and road crossings make the city a key transportation hub.

A grinding siege began last spring as waves of Russian soldiers, backed by artillery and remote-controlled drones, advanced slowly through nearby farms and villages, beginning a gradual encirclement. In the months since, Moscow has gained ground steadily but at an extremely high cost.

An analysis by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a think tank in Washington, D.C., estimated Russia had lost roughly 3,000 soldiers, killed and seriously wounded while trying to capture Pokrovsk, during a two-week period in December.

It’s unclear how many soldiers Ukraine’s forces have lost defending the city.

“The Ukrainians are very, very quiet about their attrition rates, but generally you would expect for defenders to take fewer casualties,” said George Barros, an analyst with ISW. But he acknowledged that Russia holds the advantage: “The Ukrainians are holding large swaths of territory with very few men,” he said.

As NPR’s team drove through the ghostly city, through sleet and rain in an armored car, there were Ukrainian soldiers and civilians who appeared to be barely hanging on. An elderly couple shuffled quickly down a sidewalk. A lone man rode his bicycle.

One weary-looking Ukrainian soldier named Vitalii was driving a heavily damaged U.S.-made Bradley Fighting Vehicle on the outskirts of town.

Like many of the country’s fighters, those interviewed for this article gave only their first name for security reasons.

“The situation is pretty bad,” Vitalii said. “The Russian drones are the worst.”

Vitalii used a curse word to describe the hovering machines that rain grenades and bombs almost hourly from the sky. Asked if he thinks Ukraine can hold out in Pokrovsk, Vitalii shrugged and said, “If it doesn’t work we at least have to try.”

“The guys are holding on by every means”

Pokrovsk was once home to 60,000 people, a humble industrial city. For much of the war it was relatively safe. But over the last year, Russia carved deeper into Ukrainian territory along a wide swath of the eastern front.

As the city became a target for Moscow, shelling and missile strikes escalated. Local officials said in their year-end message on Dec. 30, that 95% of industrial facilities and 70% of homes have been damaged or destroyed.

“The guys are holding on by every means,” said a gray-bearded military ambulance driver in a green cap, who gave his name as Serhii. The 58-year-old is commander of the “Shark” medical evacuation unit of the 117th Separate Heavy Mechanized Brigade. He added that some units defending the city are frustrated because they “aren’t getting the support they need.”

“It’s politics,” Serhii said. “We don’t have enough shells and other supplies.”

In December, Ukraine’s military replaced the general who was leading the defense of Pokrovsk after he failed to stop Russia’s advance. But most military analysts say the stark reality is that Russia’s army is simply much larger, fielding with more men, more artillery, more shells.

Ukraine has scrambled to respond by using drones of its own, with lethal effect. NPR was able to observe as a team on the outskirts of Pokrovsk used remote-controlled hovering aircraft to hunt and kill Russian soldiers on the battlefield. But soldiers involved in the operation said these measures likely won’t be enough.

“We try to take out as many [Russians] as we can before they reach our positions,” said a drone technician who also identified himself by a single name, Yuri. “But sometimes they’re just too many. It’s impossible to hold.”

But for now Pokrovsk is still held by the Ukrainians, a significant accomplishment for Ukraine’s beleaguered army. The fortifications and trench lines here are a part of nearly 600-mile-long defensive system holding Russia back from the heartland of Ukraine.

Barros, the analyst with ISW, said in 2024 Ukraine was forced to retreat. But its forces have also slowed Russia’s advance, while killing or injuring as many as 30,000 Russian soldiers every month along the entire front, according to estimates compiled by Barros’ group and other military analysts. He believes losses on that scale may be unsustainable for Moscow.

“Russia’s manpower is actually quite limited. Russians are struggling to offset that 30,000 casualties per month figure,” Barros said. “They have a system that’s allowed them to sustain that [loss] for the last two and a half years, but it’s not working anymore.”

It’s not clear how much longer Ukraine’s defense of Pokrovsk can hold. Military officials told NPR Russian troops and drones now regularly threaten the main highway into the city, which makes it increasingly difficult to supply troops.

Near the city’s main square, NPR found roughly a dozen people gathered at an evacuation checkpoint. They had decided it was finally time to leave, most too frightened or distressed to speak.

“It’s always like this, always the loud bombs,” said a man who gave his name as Serhii, age 62, but declined to give his last name because of the risks of living near an area occupied by Russian forces. He said the rest of his family had already fled, but he had chosen to stay until the last possible minute.

“I didn’t want to go because I was born here, it’s my hometown, but now I have to leave.”

NPR field producer Polina Lytvynova contributed reporting to this story.

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

You can find a microcosm of Ukraine’s defense against Russia by visiting a single small city. It’s called Pokrovsk. Ukrainians hold it for now, and they’re trying to stabilize their defensive lines against more numerous Russian attackers. NPR’s Brian Mann was inside the city yesterday and brings us the sounds of combat.

(SOUNDBITE OF VEHICLE WHIRRING)

BRIAN MANN, BYLINE: We drive through sleet and rain toward the northern outskirts of Pokrovsk in an armored car, navigating to avoid Russian troops that now partially encircle this place about a mile outside the city.

(SOUNDBITE OF VEHICLE HONKING)

MANN: We stop at a checkpoint where there are soldiers, medical teams and evacuation crews. I meet a 29-year-old soldier who only gives his first name, Vitale (ph), for security reasons. He’s just back from the front lines and looks worn thin.

VITALE: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: Vitale tells me it’s his job to go close to Russian positions to retrieve broken down equipment, like the American-made Bradley fighting vehicle he’s driving today. It’s been damaged by a land mine and now will be repaired and sent back into the fight. The situation’s pretty bad, Vitale says. The Russian drones are the worst. He uses a curse word to describe the hovering machines that rain bombs from the sky. I ask if he thinks Ukraine can hold out in Pokrovsk.

VITALE: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: “If it doesn’t work, we at least have to try,” he says. Pokrovsk was once home to 60,000 people. It’s crucial to the war effort for its coal and for its rail and road connections that are used by Ukraine’s army. Fortifications here have also held Russia back from cutting into the heartland of Ukraine. If Pokrovsk falls, cities like Dnipro, home to nearly 1 million people, will be far more vulnerable. Nearby, I meet Serhii (ph), a gray-haired man smoking a cigarette while leaning against the ambulance he drives. I ask what he’s seeing as he pulls wounded soldiers from the front, and he shakes his head.

SERHII: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: “The guys are holding on by every means,” he says. But he tells me Ukraine’s soldiers and Pokrovsk aren’t getting the support they need.

SERHII: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: It’s politics, Serhii says. We don’t have enough shells and other supplies. Just last week, Ukraine’s military replaced the general who was leading the defense of Pokrovsk after he failed to stop Russia’s advance. But most military analysts say the reality is Russia’s army is simply much larger, more men, more artillery, more shells.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOORS SHUTTING)

MANN: We climb back into the armored vehicle and drive deeper into the city.

So we’re in Pokrovsk now. It’s largely abandoned. I’m seeing just very few civilians, one man riding by on his bicycle. But a lot of the houses look dark, shattered by artillery and drone strikes.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARTILLERY FIRING)

MANN: Empty gray streets echo with the sound of outgoing artillery. Those are Ukrainian guns blasting at Russian positions just to the south. Remarkably, we find a small grocery and cafe still open and duck inside.

(CROSSTALK)

MANN: Svitlana Storozhko (ph) is serving a customer. When I ask if she’s frightened, she says she evacuated her pets but so far chooses to stay.

SVITLANA STOROZHKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: “We believe in God and in Ukraine’s armed forces,” she says. But this is an increasingly dangerous choice.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARTILLERY EXPLODING)

MANN: As the battle rages, we find about a dozen people who finally decided it’s time to go. They’ve turned up at an evacuation point.

SERHEI: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: It’s always like this, always the loud bombs, says an elderly man named Serhei. The rest of his family has already gone. And I ask why he stayed so long in a city with no gas for heat, no running water and war at his doorstep.

SERHEI: (Speaking Ukrainian).

MANN: “I didn’t want to go because I was born here. It’s my hometown,” Serhei says. “But now I have to leave.”

Brian Mann, NPR News, in Pokrovsk in eastern Ukraine.

(SOUNDBITE OF STRONG.AL& AND CLOUDSURFIN’S “AURORA”)

Jurassic footprints are discovered on a ‘dinosaur highway’ in southern England

The 166-million-year-old footprint tracks, found at a quarry in southern England, mark one of the largest discoveries in decades.

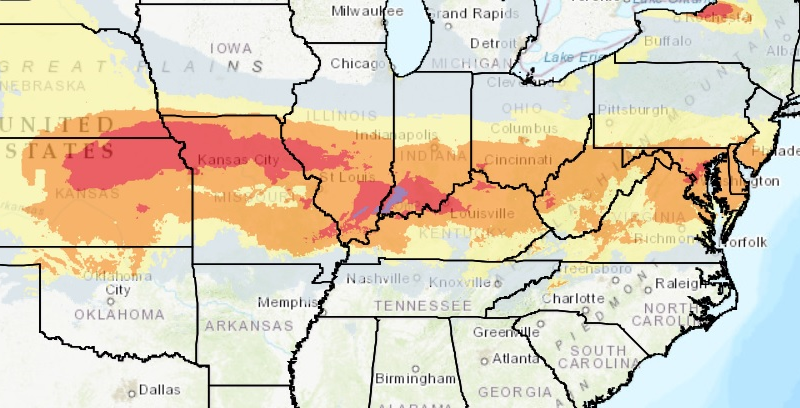

A storm will bring heavy snow and dangerous ice from the Plains to the East Coast

This weekend's storm is expected to impact 62 million Americans through Monday. Heavy snow, ice, rain and severe thunderstorms will be unleashed from the Plains to the East Coast.

Film director and screenwriter Jeff Baena, husband of Aubrey Plaza, dead at 47

The co-writer of I Heart Huckabees and director of The Little Hours was found dead at a Los Angeles residence on Friday. The Los Angeles Police Department is investigating the case.

A Pulitzer winner quits ‘Washington Post’ after a cartoon on Bezos is killed

Washington Post cartoonist Ann Telnaes resigned after an editor rejected her sketch satirizing tech chiefs, including the Post's owner and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

How influencers are impacting journalism

NPR's Eric Deggans speaks to Summer Harlow of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas and V Spehar of UnderTheDeskNews about the role of influencers in journalism.

Vehicular attacks are not new. But preventing them has been a big challenge

For decades, individuals and terrorist groups have used vehicles to carry out deadly attacks. But installing safeguards hasn't always been successful.