Trump’s threats of mass deportations lead to hard discussions for families

NEW YORK — It’s almost bedtime and Angel Reyes Rivas is going through a universal parent routine, alternating between begging his toddlers to simmer down and issuing warnings.

As he negotiates, he tells me that on the rare instances when he and his wife have some alone time they’ve been having a terrifying conversation: what to do if one of them gets deported.

They started having that discussion earlier this month, when former President Trump was reelected, largely on the promise of mass deportations.

Reyes Rivas is originally from Peru. His wife is from Colombia.

Neither of them are in the U.S. with permanent legal status, but their children are.

Similar conversations are taking place in families across the country.

Throughout the presidential campaign season, immigration was largely framed as an “Americans citizens vs. immigrants” issue, but for approximately 11 million American citizens who live in families with mixed immigration status, mass deportations could be devastating.

Wennie Chin, senior director of community and civic engagement at the nonprofit New York Immigrant Coalition, says, “Often folks fixate on the number of undocumented immigrants in the country. But deportation is not just their lives at stake. Immigrant rights are American rights.”

“I can tell you from firsthand experience, a deportation is the worst thing that can happen to your family,” says Reyes Rivas. “I wouldn’t want my kids going through something like that.”

When Reyes Rivas was 19, during the Obama administration, his mother got deported. Suddenly, he was a teenager in charge of his 13-year-old brother.

No one had ever told him what to do if this happened. He says it was emotionally and financially devastating.

These days, he works in a cellphone repair business and as an immigration advocate.

He says he’s been warning immigrant communities that “part two of the Trump administration is going to be something that we haven’t seen before. Get to know your rights. Get ready. Talk to your kids. Look into how you’re going to handle being detained, being deported.”

Reyes Rivas has DACA, a temporary protection against deportation for some people brought to the U.S. as undocumented children. This program, created by the Obama administration, is facing legal challenges in courts.

The incoming Trump administration could end the program, and Reyes Rivas might find himself undocumented again.

He says he can’t find it in his heart to explain the potential situation to their children.

“I don’t want to put in their heads that they’re going to separate me from you. I mean who wants to have that conversation with their kids, right?”

For many mixed status families, this conversation is nothing new. It’s been happening for an entire lifetime.

At La Morada restaurant in the Bronx, Carolina Saavedra recalls that she was 8 years old when her parents bought her and her siblings a piece of jewelry, then explained what the kids should do if their parents got deported.

“You take that piece of jewelry and you sell it. And you find a church and you ask for help there. I remember it was a gold necklace, with two dolphins on it.”

Saavedra was born in the U.S., but her parents are undocumented, originally from Oaxaca, Mexico.

“I was raised with the fear that one day, deportation will happen. It’s bound to happen. So we always had a game plan in action.”

They were so worried about being separated, they would bake the instructions into her bed time stories. She’s 31 years old, and still knows the story by heart.

“Long ago there was a little girl and her mom. The bad guys were coming. And the daughter sold the piece of jewelry that they had. They made it to the next safe land, and they lived happily ever after.”

The Saavedra family owns this restaurant. Over the last 15 years, La Morada has become a hub of the community, doubling as a mutual aid for neighbors and recently arrived migrants.

And yet one thing never budges: they’ve been undocumented for over three decades. And there’s a sense of disenchantment with both political parties for not providing a path to legal status.

“My parents have been paying taxes since before I was born,” Saavedra says. “We’ve been putting into the fabric of the American economic system for so many years. But there is no path to citizenship.”

She says any sense of safety, stability and a future has come from their neighbors. “We have this saying here: in community there is immunity.”

As lunch hour rush dies down, her mother, Natalia Mendez, sits down with me. I ask if she’s nervous about the incoming Trump administration.

She tells me an anecdote about when she first arrived: there was a raid at the factory she worked in, and a colleague helped her escape through a laundry chute. This happened several times back in the ’90s. It was during the Clinton presidency.

“You see, there is nothing new under this sun,” Mendez says, before heading back to her kitchen.

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

Aside from closing the border, the president-elect has promised mass deportations of people already in the United States, and that promise would affect a lot of United States citizens. An immigration nonprofit estimates that more than 11 million citizens live in a household that includes someone without legal status, and the threat of deportation has led to some hard family talks. NPR’s Jasmine Garsd has been listening.

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD: (Non-English language spoken).

JASMINE GARSD, BYLINE: It’s almost bedtime. In Long Island, New York, Angel Reyes Rivas is trying to get his toddlers to simmer down. As he goes through the universal parent routine – begging and issuing warnings – he tells me when they get time alone, he and his wife have been having a terrifying conversation – what to do if one of them gets deported. He’s from Peru. She’s from Colombia.

ANGEL REYES RIVAS: I can tell you from firsthand experience that a deportation – it’s, like, the worst thing that could happen to your family. I wouldn’t want my kids going through something like that ’cause it’s difficult.

GARSD: He knows. When Reyes was 19, his own mother got deported. It was during the Obama years. Suddenly, he was a teenager in charge of a family. No one had ever told him what to do if this happened. These days, Reyes is an immigration advocate. He says he’s been warning immigrant communities.

REYES: Part 2 of the Trump administration – it’s going to be something that we haven’t seen before. It’s like, get to know your rights. You know, get ready. Talk to your kids. Look into, you know, how you’re going to handle being detained, being deported.

GARSD: Reyes himself has DACA, a protection for people brought to the U.S. as undocumented children. Under a Trump administration, that program could end. His wife is undocumented. Their kids, both toddlers, were born in the U.S. He says he can’t bring himself to explain it to them.

REYES: No. Like, I don’t want to put in their heads that they’re going to separate me from you, right? I mean, who wants to have that conversation with their kids, right?

GARSD: For many mixed-status families, this conversation is nothing new. Carolina Saavedra says when she was 8 years old, her parents bought her and her siblings a piece of gold jewelry. And they explained what the kids should do if their parents got deported.

CAROLINA SAAVEDRA: You take that piece of jewelry and you sell it. And you find a church, and you ask for help there.

GARSD: Saavedra was born in the U.S. She’s a citizen. Her parents are undocumented, originally from Oaxaca, Mexico. They were so worried, they would bake the instructions into her bedtime stories. She still knows the story by heart.

SAAVEDRA: Long ago, there was a little girl and her mom. And the bad guys were coming, and the daughter sold the piece of jewelry that they had. They made it to the next safe land, and they lived happily ever after.

GARSD: The Saavedras own this restaurant. It’s called La Morada. For 15 years, it’s been a hub of the community, doubling as a mutual aid for neighbors and recently arrived migrants. And yet, one thing never budges. They’ve been undocumented for over three decades, with no path to legalization. As lunch hour rush dies down, mom, Natalia Mendez, sits down with me. Is she nervous about the incoming Trump administration?

NATALIA MENDEZ: (Speaking Spanish).

GARSD: She tells me an anecdote about this one time, when she first arrived, there was a raid at the factory she worked in. She escaped through a laundry chute. This happened several times back in the ’90s, during Clinton. There is nothing new under this sun, she says, before heading back to her kitchen. Jasmine Garsd, NPR News, New York.

Sudan’s biggest refugee camp was already struck with famine. Now it’s being shelled

The siege, blamed on the Rapid Support Forces, has sparked a new humanitarian catastrophe and marks an alarming turning point in the Darfur region, already overrun by violence.

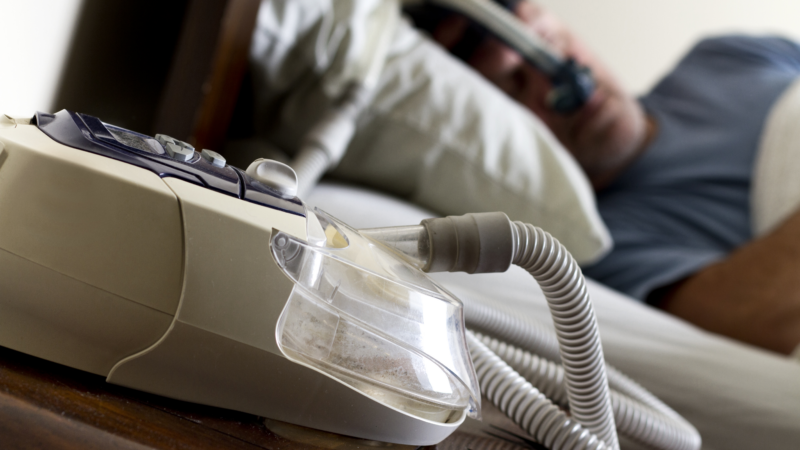

FDA approves weight loss drug Zepbound to treat obstructive sleep apnea

The FDA said studies have shown that by aiding weight loss, Zepbound improves sleep apnea symptoms in some patients.

Netflix is dreaming of a glitch-free Christmas with 2 major NFL games set

It comes weeks after Netflix's attempt to broadcast live boxing between Jake Paul and Mike Tyson was rife with technical glitches.

Opinion: The Pope wants priests to lighten up

A reflection on the comedy stylings of Pope Francis, who is telling priests to lighten up and not be so dour.

The FDA restricts a psychoactive mushroom used in some edibles

The Food and Drug Administration has told food manufacturers the psychoactive mushroom Amanita muscaria isn't authorized for food, including edibles, because it doesn't meet safety standards.

The jury’s in: You won’t miss anything watching this movie from the couch

There's been a bit of consternation flying around about the fact that the theatrical release of Juror #2, directed by Clint Eastwood, was very muted. But this movie is perfect to watch at home.