To hit deep inside Russia, Ukraine has built its own drones

It’s drone testing day at a farm field outside Ukraine’s capital Kyiv, where several Ukrainian drone makers are demonstrating their latest models for Ukraine’s military.

“This is the final stage where they need to fly for four hours to see how the battery will work,” said Victor Lokotkov. He’s with Airlogix, a company that’s just updated its reconnaissance drones, which are already in use by Ukrainian troops. If these drones fly as planned today, “tomorrow they will go to the frontline,” he added.

That’s the kind of instant turnaround most militaries can only dream of — and it’s a new development for Ukraine as well. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukraine’s traditional air force was, and is, no match for Russia. Ukraine had only a tiny domestic drone industry. The country also lacked long-range missiles. All of this meant the country had no way to carry out strikes across the border against Russian forces.

Today, dozens of Ukrainian companies are making drones that play a critical role in the war. Many of those drones are doing reconnaissance work or carrying out attacks along the frontline inside Ukraine. But increasingly, Ukraine is sending attack drones deep into Russia to hit air bases, weapons depots and fuel storage sites.

“Most of the companies here are the companies that were created a couple of years ago, or even a couple of months ago,” Lokotkov said of those at the testing ground.

Holding off Russian forces

President Biden recently gave Ukraine permission to use U.S. ballistic missiles, known as ATACMS, for strikes inside Russia. Previously, Ukraine was only able to use them against Russian forces inside Ukraine.

Ukraine fired seven of those powerful missiles at Russian military targets in southwest Russia on Tuesday, though it was not immediately clear how much damage they caused. While Ukraine had long sought such permission, it has received only a limited number of ATACMS. Therefore, it is still expected to rely heavily on its own drones for many attacks on Russian soil.

The drones are also playing a key role in eastern Ukraine, where Russian forces are pressing an offensive against outnumbered and outgunned Ukrainian troops.

In many cases, Ukrainian attack drones are helping to stop, or at least limit, Russian gains. The drones, which can drop grenades and other explosives with precision, target Russian troops as they attempt to push across the no-man’s land separating the two armies on the frontline.

“It is breathtaking how fast the technology and the tactics have changed,” said Kelly Grieco, with the Stimson Center in Washington. She closely covers the air war in Ukraine and recently briefed the Pentagon.

Just a couple years ago, Ukraine relied on large, slow Turkish drones. Now the Ukrainians use homemade models that are smaller, faster and much cheaper.

“We’re seeing these really small racing drones flying through trees and attacking the enemy,” she said. “And of course, these long-range, one-way attack drones that are allowing Ukraine to strike in Russian territory.”

This has, to some extent, neutralized Russia’s air advantages.

Russia has more than 1,000 top-end fighter jets inside Russia, yet they rarely venture into Ukrainian air space because of the risk of being shot down.

Ukraine sends up its $1,000 drones as fast as it can make them and doesn’t have to worry about losing a pilot.

“In some ways, what we’re seeing is a 21st-century military fighting a 20th-century one — Ukraine being the 21st-century military,” she said.

The air war in Ukraine may hold important lessons for the U.S. and other militaries worldwide.

“The approach we’ve seen in Ukraine, of relatively inexpensive experimentation that cycles fast, is pretty alien to the U.S. way of doing defense policy,” said Stephen Biddle, a professor at Columbia University who’s advised the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The U.S. approach, he says, “has been invest in very sophisticated, very high performance, very costly weapons that you therefore won’t be able to buy in large numbers. Is it really the right plan to have small numbers of very expensive, very sophisticated weapons?”

The best-known U.S. drones — multimillion-dollar Reapers and Predators — flew unchallenged in the skies over Iraq and Afghanistan. But they would be easy targets in Ukraine, and therefore aren’t being used by the Ukrainians.

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said, following a recent visit to Kyiv, that the Americans are investing in Ukraine’s drone industry.

The Ukrainians have developed “the capability to mass produce drones that are very, very effective. We’ve seen them strike targets that are 400 kilometers (250 miles) beyond the border. And they can do that at a fraction of a cost of a ballistic missile. So, it makes sense to invest in that capability.”

In recent months, multiple media reports, including some from inside Russia, have cited drone attacks at military bases in Murmansk, a Russian town in the Arctic Circle, more than 1,000 miles from Ukraine’s border.

Ukraine pioneers the use of sea drones

Ukraine’s drones are not only in the sky, they’re also in the Black Sea.

Ukraine initially built sea drones that were essentially jet skis packed with explosives. They were so effective against Russian ships in the Black Sea that the Ukrainians are now building their own more sophisticated, and more powerful, sea drones.

Using a variety of weapons, Ukraine has sunk around 25 Russian ships and submarines.

“Somehow, this country without a traditional navy has managed to sink or disable a third of Russia’s Black Sea fleet and force it to withdraw it further back in Russia,” said Grieco. “That is an amazing accomplishment.”

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is setting ambitious targets for Ukraine’s overall drone program. He says the country will build around 2 million this year, and plans to make around 4 million next year.

Russia is feeling the sting of these attacks and is ramping up its own use of drones.

The drones alone won’t win the war, but they are keeping Ukraine in the fight.

Party City files for bankruptcy and plans to shutter nationwide

Party City was once unmatched in its vast selection of affordable celebration goods. But over the years, competition stacked up at Walmart, Target, Spirit Halloween, and especially Amazon.

Sudan’s biggest refugee camp was already struck with famine. Now it’s being shelled

The siege, blamed on the Rapid Support Forces, has sparked a new humanitarian catastrophe and marks an alarming turning point in the Darfur region, already overrun by violence.

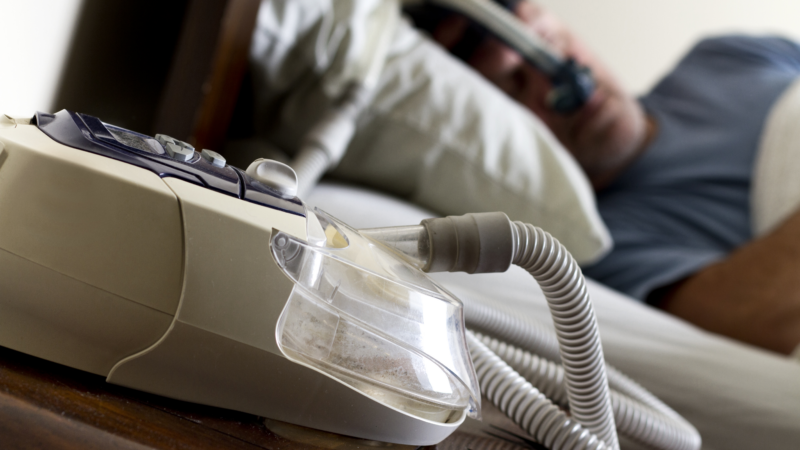

FDA approves weight loss drug Zepbound to treat obstructive sleep apnea

The FDA said studies have shown that by aiding weight loss, Zepbound improves sleep apnea symptoms in some patients.

Netflix is dreaming of a glitch-free Christmas with 2 major NFL games set

It comes weeks after Netflix's attempt to broadcast live boxing between Jake Paul and Mike Tyson was rife with technical glitches.

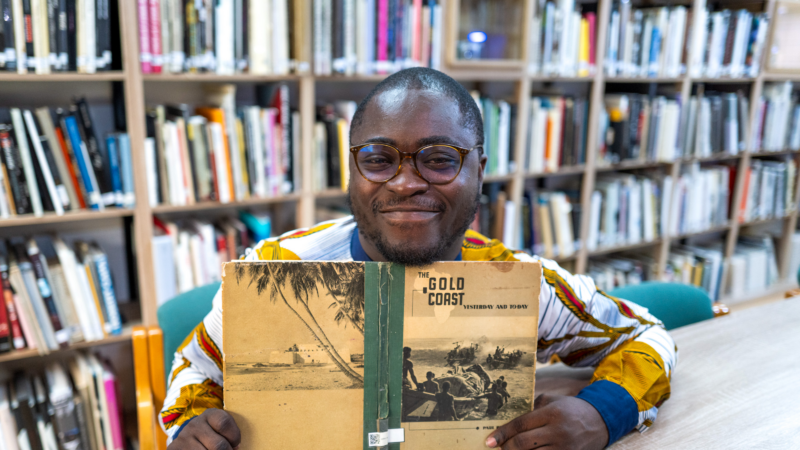

Big dreams: He’s the founder of a leading African photobook library

Paul Ninson had an old-school, newfangled dream: a modern library devoted to photobooks showing life on the continent. He maxed out his credit cards, injured his back — and made it happen.

Opinion: The Pope wants priests to lighten up

A reflection on the comedy stylings of Pope Francis, who is telling priests to lighten up and not be so dour.