The true story of a famed librarian and the secret she guarded closely

The name Belle da Costa Greene might not ring a bell, but New York’s historic Morgan Library and Museum is trying to change that.

A new exhibit called “A Librarian’s Legacy” opened this month, just in time for the Morgan’s 100th anniversary. It traces Greene’s life and her lasting influence as the library’s first director.

It was an unusually prominent role for a woman at the time — a Black woman who chose to pass as white to survive in a highly segregated America.

Changing the family name

Greene was appointed the director and inaugural librarian of the Morgan, which was founded by J. Pierpont Morgan — the American financier.

During her tenure, she collected parts of the Crusader Bible, medieval works, historic manuscripts and more. But it was how Greene lived her life beyond the library walls that may ignite deeper curiosity among exhibit goers.

According to exhibit curator Erica Ciallela, the decision to pass as a white woman wasn’t entirely Greene’s own.

“It was really spearheaded by her mother, Genevieve, who not only made the decision for Belle Greene and her siblings to pass, but did it fairly early on when Greene was still in school,” Ciallela told All Things Considered.

The decision came after Greene’s mother, Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener, separated from Belle’s father, Richard T. Greener, the first Black graduate of Harvard College, in the 1890s.

At the time, the then-named Greeners lived in Washington, D.C.’s Black high society. After the separation, Genevieve dropped the last letter of their family name and was lighter-skinned enough to pass as white, as were Greene’s siblings.

This opened doors for Belle da Costa Greene in segregated America, and she worked at Princeton before joining the research library. There she met a cousin of J. Pierpont Morgan, who at the time was looking for someone to organize his growing collection.

“The interview went amazingly, as we can all imagine,” Ciallela said. “And in 1905, she began working for Pierpont Morgan as his librarian, cataloging his collection and eventually starting this amazing building that we have and are celebrating still today.”

Attention from the newspapers

Being a woman librarian and director of a major institution was a big deal at the time. Greene was able to achieve what most women could not, especially during a time when they had just gotten the right to vote.

It wasn’t unheard of for Greene to be one of only two women on auction floors, and the position made her known in collector circles. It also made her a feature in newspapers and other reports. Greene’s face was seen globally and she was photographed often and shown in trade publications for rare book collectors.

“We do know that newspaper reporters always would notice her complexion. They would always point out her dark hair or her wild hair or their darker skin color,” Ciallela said.

Yet there is no record of Greene’s thoughts about passing as a white woman. Before she died in 1950, she burned her 10-volume journals and diaries.

Ciallela said Greene “wrote things down that she dare not even think to herself” in those journals. She also slowly retreated from public view as she aged, and as her natural features became more pronounced, Ciallela said.

Exhibit attendees may never truly know why Greene chose to pass as white, but the Morgan Library’s exhibit describes how her legacy spans generations and ripples through libraries today.

“She loved being a librarian. That was her essence,” Ciallela said. “She was so proud of everything she was building here and she created a family with this staff here. And so I really think that her work kept her moving forward and kept her eyes on, you know, ‘I might be hiding this portion of myself, but the world gets to see all of this other stuff that I am accomplishing.’”

“A Librarian’s Legacy” will run until May 4, 2025, and include a walk through Greene’s early life in Washington, D.C. This is new research, Ciallela said, and ties in the librarian’s roots with the continual tradition of Black librarians in the United States.

The interview with Erica Ciallela was conducted by Ailsa Chang, produced by Jordan-Marie Smith and edited by Jeanette Woods.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

The name Belle da Costa Greene might not ring a bell, but New York’s renowned historic Morgan Library and Museum is trying to change that. A new exhibit called “A Librarian’s Legacy” opens today, just in time for the Morgan’s 100th anniversary. It traces Greene’s life and her lasting influence as the library’s first director and collector. It was an unusually prominent role for a woman at the time – a woman who chose to pass as white to survive in a highly segregated America.

The Morgan Library was built and founded by J. Pierpont Morgan, one of the richest and most powerful bankers in the early 20th century. It houses a one-of-a-kind collection of medieval writings, rare books and illuminated manuscripts, thanks in large part to Belle da Costa Greene. Erica Ciallela is an exhibit curator for “A Librarian’s Legacy” at the Morgan Library, and she joins us now. Welcome.

ERICA CIALLELA: Thank you so much for having me. I’m excited to talk about Belle Greene.

CHANG: Oh, well, we’re so excited to have you. So just explain, first of all – like, how did Belle da Costa Greene come to be associated with the Morgan Library in the first place?

CIALLELA: Yeah, so she just was working as a librarian at Princeton University and really caught the attention of a gentleman by the name of Junius Morgan, who was an associate librarian there and just happened to be the nephew of Pierpont Morgan, who was, at this time, in the city, wondering what to do with his amazing collection he had already start to collect and was, unfortunately, just kind of everywhere in his home. And he decided to build a library next door to his townhouse on Madison, and he needed a librarian to run it. And Junius said, I think I have the perfect person for you. And in 1905, she began working for Pierpont Morgan as his librarian, cataloging his collection and eventually stewarding this amazing building that we have and are celebrating still today.

CHANG: I love that. I want to talk a little bit about her personal story because Greene – I mean, she was a Black woman, but she didn’t live her life publicly as a Black woman. She chose to pass as white. Can you talk about that – like, why she felt she had to do that? How did she do that? Please, tell me more.

CIALLELA: Yes, of course. I mean, the decision to pass was actually a family choice, and it was really spearheaded by her mother, Genevieve, who not only made the decision for all of Greene and her siblings to pass, but did it fairly early on, when Greene was still in school. She had lived in Washington, D.C. She had lived previously in South Carolina and really saw the struggles of what it meant to be African American in this country, what it was like during Reconstruction in the South. And so she really kind of knew that, in order to move forward, sometimes you have to do what you have to do.

CHANG: Did anyone ever suspect that she was not white? Do you know of any incident, any confrontation?

CIALLELA: We do know that, like, newspaper reporters – they would always point out her dark hair or her wild hair or the darker skin color.

CHANG: Her wild hair – wow. And do you have any sense of what that did in the long term to her psyche, her identity, passing as white day-to-day for so much of her life?

CIALLELA: She had a 10-volume set of diaries, and she does burn these before she passes away. But we do have a letter she wrote to the art historian, Bernard Berenson, where she said that she – that is where she wrote things down that she dare not even think to herself. So what that means, unfortunately we’re never going to know. But, I mean, it’s got to have been a struggle. And, I mean, it’s actually incredible that she was made director as a woman.

CHANG: Yeah.

CIALLELA: I mean, most directors of these kinds of institutions were not women at this time, either. So she had – you know, there’s not only the racial issue she was up against but the gender ones as well. I mean, she becomes director very shortly after women gained the right to vote. So, I mean, this is really an important time in American history to think of what women’s rights in general were at this time and how much she was saying, I’m not going to conform to these ideals. I’m going to be my own person.

CHANG: That’s so cool. How would you characterize her larger legacy outside of the Morgan Library, looking back on all of this?

CIALLELA: She really believed in accessing a collection, being able to use a collection – that it shouldn’t just sit on a shelf – that she really wanted people to interact with that. And that’s something that librarians today hold dear. But it wasn’t the trend back then, and she really was a trailblazer for a special collection being used and not just something pretty you look at – but what can we learn from it? How do we access it? And that everyone – she really believed that everyone should have access to these materials, not just the super wealthy. And I think that is really a testament to her and the legacy she leaves behind to a much more larger library community.

CHANG: I can’t wait to check this out. Erica Ciallela, an exhibit curator for “A Librarian’s Legacy,” the Morgan Library’s exhibit on its first ever director and librarian, Belle da Costa Greene. It opens today in New York. Thank you so much for speaking with us, Erica.

CIALLELA: Thank you for having me.

How has the Electoral College survived, despite being perennially unpopular?

Despite its substantial-sounding name, the Electoral College isn’t a permanent body: It’s more of a process. For decades, a majority of Americans have wanted it to be changed.

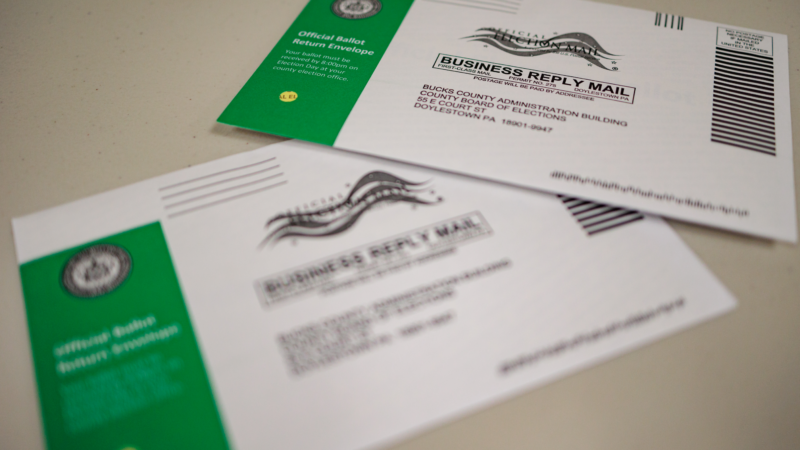

Thousands of Pennsylvania voters have had their mail ballot applications challenged

Thousands of last-minute challenges to voters’ mail ballot applications, along with baseless claims by former President Donald Trump, are adding pressure on Pennsylvania county officials.

No more fluoride in the water? RFK Jr. wants that and Trump says it ‘sounds OK’

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s claims about fluoride in the drinking water are linked to Cold War conspiracy theories about the substance.

‘Divine Nine’ historically Black organizations hope efforts will turn out the vote

With more than 2 million members, the "Divine Nine" organizations have launched many get-out-the-vote initiatives in this historic election involving one of their members, Vice President Harris.

Impossible, you say? Try asking a toddler

Green eggs and ham? Even toddlers know when an event appears to be impossible, not just improbable.

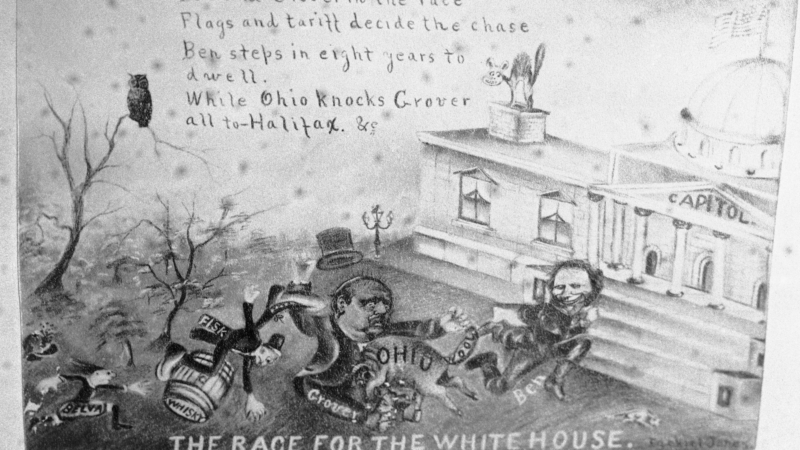

Trump is hoping to win non-consecutive terms. Only one president has done it

If reelected, Trump would only be the second president to serve non-consecutive terms after Grover Cleveland in the late 1800s. Here's a look at how that happened — and who else has tried.