The Assad regime’s fall has freed displaced Syrians stuck in a remote desert camp

RUKBAN CAMP, southern Syria — For almost a decade, thousands of displaced Syrians trapped in the desert struggled to survive in one of the most remote camps in the world; left without aid or medical care and largely forgotten by the outside world.

The Syrians — some of them soldiers and relatives of the U.S. -backed Syrian Free Army forces against now-deposed President Bashar al-Assad — arrived fleeing ISIS when the militant group swept into Iraq and Syria in 2014. They massed in a desolate corner of southeastern Syria up against the Jordanian border and hemmed in by Syrian regime and Russian forces on the other side.

With the fall of the Syrian regime this month, the more than 7,000 camp residents are finally free to leave. But the years of deprivation and isolation have taken a heavy toll.

The existence of the community speaks to the complicated regional politics and the low-profile U.S. military role in Syria, as well as the possibility of dramatic transformation in seemingly unchanging conflicts.

When Jordan sealed its border in 2016 after an ISIS attack killed six Jordanian soldiers, most of the Syrian civilians were trapped — unable to move forward or go back through roads controlled by the Syrian regime or even move through a desert laid with land mines.

NPR traveled to the camp, about a five-hour drive from Damascus — the first journalists to ever go there, according to the main relief organization here, the U.S.-based Syrian Emergency Task Force. The camp is about 30 miles from the U.S. military’s al-Tanf garrison, established in 2016.

In January, Iran-backed Iraqi militia drones attacked a U.S. military support base — Tower 22 — just a few miles over a sand berm and across the border in Jordan, killing three American troops.

Tanks abandoned by regime forces line the main M2 highway, the roadside dotted with cast-off uniforms. Past the U.S. base, the road turns into a rough desert trail of tracks through the black rock.

“Before 2014 there were no people here at all,” says Abu Mohammad Khudr, who dispenses medication from a tiny pharmacy established two years ago by Syrian Emergency Task Force. “We thought maybe the neighboring countries would help us but they didn’t.”

The first residents came with tents, which were no match for the constant wind, searing heat and bitter cold of the desert.

“After a while we decided we had to use the soil and water — so we made bricks and then we made walls and we built houses,” he says.

After the suicide bombing, Jordan sealed the border — preventing even aid agencies from delivering food to Rukban. Water though is still provided by UNICEF, pumped from Jordan.

The sun-dried clay bricks, made by hand, are still the only building material for homes here. Instead of glass, small sheets of clear plastic cover the small window openings.

With Syrian regime forces and Russian troops controlling the road out of the camp, food was in short supply and sometimes consisted only of dried bread or lentils and rice.

“Most families ate just one or two meals a day,” says Khudr.

In one home, Afaf Abdo Mohammed says when her children were infants she used plastic bags instead of diapers.

Her 16-year-old daughter, She’ala Hjab Khaled, was born with a spinal defect and spends the entire day sitting in a battered wheelchair. Syrian Emergency Task Force opened eight schools here two years ago, staffed with volunteer teachers from the camp. But She’ala has never been.

“I can’t get there,” she says.

Now free to leave, with the fall of the Syrian regime, very few residents have money for transportation to leave. Many are not sure if their homes still exist.

Among Syria’s many and complex tragedies, the camp has been a particular preoccupation of Mouaz Moustafa, an activist and the director of the Syrian Emergency Task Force.

Two years ago he began organizing aid shipments for al-Tanf through a provision that allows humanitarian aid to be carried in unused space on U.S. military aircraft. He started bringing in American medical volunteers on two-week missions and persuaded the base commander at the time to visit the camp. Since then he says, U.S. forces have been involved in distributing aid there and when they are able, providing emergency medical care.

“It really brought everyone together more,” says Moustafa. Syrian Emergency Task Force is funded by donations and staffed largely by volunteers. He says some of the soldiers who helped with the aid missions came back to Rukban to volunteer after being discharged.

That humanitarian assistance is not something the U.S. military publicizes. The U.S. military command over the years has declined to bring in visiting journalists to its nearby base — the only access route before the fall of the regime.

Syrian fighters funded and trained by the United States raised families in Rukban, according to a senior U.S. military commander. He requested anonymity to be able to speak about the camp because he was not authorized to speak publicly about it.

He said doctors on the base had delivered at least 100 of their babies at the base in the case of high-risk pregnancies.

The al-Tanf garrison, originally a special forces base, is now part of the anti-ISIS mission in Iraq and Syria. The presence of the U.S. military there helped protect residents from potential attacks by regime forces, he said.

Near the water pipes that supply the camp, boys come to fill up smaller tanks and to chase each other in the desert.

The environment here is filled with snakes and scorpions — but no trees. Some of the children have never tasted fruit. They’ve never seen in real life bright flowers or butterflies like the ones painted on the walls of the mud-brick schools set up by the Syrian American organization.

Winter here is particularly cruel. Those who can afford to buy sticks of wood to burn in small metal stoves for heat.

In one of the clay houses, Fawaz al-Taleb, a veterinarian in his home city of Homs, said he couldn’t afford to buy wood this year.

“We burn plastic bags, bottles, strips of old tires,” he says. “This has been our life for years.”

Respiratory and other diseases are rampant here. For almost a decade, without a single physician in this camp, when children died, their parents often didn’t know why.

Outside Taleb’s home, there are the beginnings of a garden started with seeds distributed by Moustafa’s organization to camp residents. There isn’t much that grows in the barren ground here, but Taleb points out fledgling mint, garlic and potato plants. Next to them are lillies and a rose bush.

“I’ve been trying to plant hope,” he says. “We want to live, we don’t want to say ‘we were born here and might die here.’ No matter how bad the situation, we still want to live.”

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

We begin at a refugee camp in Syria, which no journalist had seen until NPR’s Jane Arraf arrived. This camp is far from the capital, Damascus. It’s on Syria’s border with Jordan. Seven thousand people were isolated there until the old government fell recently. Here’s Jane’s report from Rukban.

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #1: (Speaking Arabic).

JANE ARRAF, BYLINE: These children chasing each other in the sand were born here in this remote desert encampment. Miles and miles of rocky desert. No water. No shade. Constant wind. It’s a place no one would ever choose to live. But nine years ago, Syrians fleeing ISIS left their homes and massed here in the desert of Southern Syria, hoping Jordan would let them in. For a while, it did. But then the gates slammed shut, leaving them hemmed in by ISIS and regime forces. And the community grew. Children were born here, and children died. Without a single doctor here, in a lot of cases, no one ever knew why. They’ve seen snakes and scorpions, but a lot of these kids have never seen a tree. Some have never tasted fruit. They’ve only seen a few visitors before, and certainly no journalists.

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #2: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: One of the kids asks for a water pipe, another for cigarettes. Until the Syrian regime fell nearly two weeks ago, this community of 7,000 people was cut off from the outside world. Many of the men here fought with opposition forces. Syrian and Russian troops controlled the highway out. The desert was mined. I’ve been trying for years to get here. The U.S. military has a base near here, but it wouldn’t bring in journalists. Jordan said it was too dangerous to let people across.

MOUAZ MOUSTAFA: You are the first journalist from anywhere of any kind to ever make it here – ever.

ARRAF: That’s Mouaz Moustafa, an activist and the director of a U.S. organization – the Syrian Emergency Task Force. In 2016, the U.S. military established its small base about 30 miles from here as part of its anti-ISIS operations. Two years ago, Moustafa persuaded the military to bring in medical supplies and visiting doctors when they had space on their aircraft.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Speaking Arabic).

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD #3: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Water here comes from UNICEF, piped in across the border from Jordan. For the past several years, Jordan has not allowed even aid deliveries, saying it’s too dangerous for aid groups to enter. It sealed the border in 2016 after a suicide bomber killed six Jordanian soldiers. And there are other dangers.

I’m standing in front of a sand berm about six feet high, with a trench in the middle. On the other side is Jordan and an American base – Tower 22. It’s essentially a support base for their outpost here in Syria at Al-Tanf. It was the base that was attacked by Iranian drones earlier this year.

Three American soldiers were killed in that attack. Moustafa says until he persuaded the U.S. military to visit the camp, there was almost no contact. After that, he says, the U.S. base embraced the community, helping to bring in and distribute aid and providing medical care when it could. The U.S. military declined to speak about the camp. Funded by donations, Moustafa’s group opened a pharmacy and started a school. It even took a census and held elections.

ABU MOHAMMAD KHUDR: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: “Nine years we’ve been without a doctor,” Abu Mohammad Khudr says. He had to leave school after the ninth grade, but he runs the pharmacy funded by the American organization.

KHUDR: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: He says all the medicine here is from the U.S.

KHUDR: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Allergy cream and infant formula and baby cereal. Antibiotics.

KHALED HAMADI: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Khaled Hamadi comes in for blood pressure medication. They don’t have a lot, but whatever they have is provided free. People here first came with tents, but they were no match for the wind, cold and heat.

KHUDR: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: “After a while, we decided to use the clay to make bricks and then walls, and then we built houses,” Khudr says. “We came here because of the border. We thought maybe the neighboring countries would help us. But unfortunately, they didn’t.”

The few here who had some money could buy food smuggled in past regime forces, but most people survived on dried bread, lentils and rice.

KHUDR: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Khudr takes us to his home for breakfast, a relative feast now that the road is open – cheese and olives and flavorful beans. There are small openings in the mud brick walls for windows, covered with clear plastic instead of glass.

AFAF ABU MOHAMMAD: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: For years, there were no diapers for babies. At another home, Afaf Abu Mohammad tells us that when her children were infants, she used plastic bags. Her eldest daughter, Sha’ela Hjib, is 16. She was born with a spinal defect and can’t walk. The parents were told once by a visiting doctor it could be corrected with surgery, but here that’s a distant dream. In their hometowns, these people came from all backgrounds – farmers, teachers. Fawaz Taleb was a veterinarian when he fled Homs in 2015.

FAWAZ TALEB: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: He shows us the mud brick rooms his family lives in. They can’t afford to buy the sticks of wood that are sold for fuel. So in winter, they burn plastic bags and even strips of old tires for heat.

TALEB: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: “The children here have a lot of chest problems because of this,” he says. Almost everyone says they’d leave here and go home now if they could. For now, they’re waiting for help – for money to rent trucks to take them back. But they’re overjoyed that they’re no longer trapped.

On the way to Rukban the day before, we meet one family on the highway that managed to leave the desolate camp. The old truck is piled high with iron bars from their dismantled roof and mattresses.

FADI FALAH: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: Fadi Falah says he’s taking his family back to Homs.

FALAH: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: “Freedom,” he keeps saying. “There is nothing more beautiful than freedom.”

FALAH: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: All four of the children crammed into the front seat were born in the camp. We’re accompanied by Moustafa, who’s practically bouncing with excitement to see families returning home.

MOUSTAFA: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: “Thank God. A thousand congratulations,” he tells the family.

OBAIDA ARNAOUT: (Singing in Arabic).

ARRAF: Back in the vehicle, an official from the interim Syrian foreign ministry – Obaida Arnaout, who’s also on the journey – starts singing about Homs, also his hometown.

MOUSTAFA: He’s saying, “Take me back to Homs. My eyes have been crying for you, Homs.”

ARNAOUT: (Singing in Arabic).

ARRAF: It was one of the many songs forbidden in the past. But for now, these few days after the fall of the regime, the future is an open road.

Jane Arraf, NPR News, in the Southern Syrian desert.

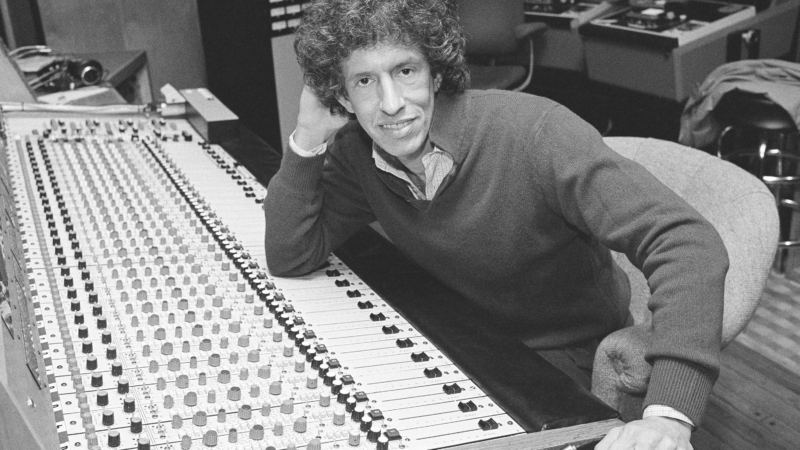

Richard Perry, record producer behind ‘You’re So Vain’ and other hits, dies at 82

A recipient of a Grammys Trustee Award in 2015, Richard Perry died at a Los Angeles hospital on Tuesday. Perry was a hitmaking record producer with a flair for both standards and contemporary sounds.

Mariah Carey and K-pop group Stray Kids rule this week’s charts

Holiday music rules the pop charts once again this week, as Mariah Carey's "All I Want for Christmas Is You" scores its 17th nonconsecutive week at No. 1 — the third longest run of all time.

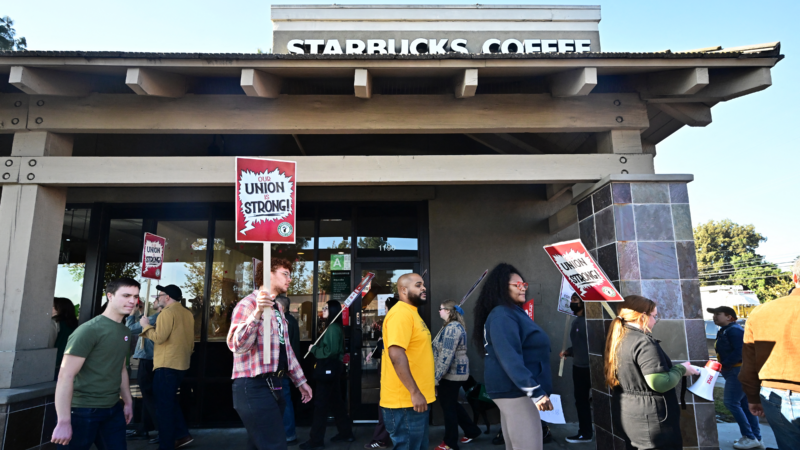

Starbucks baristas’ ‘strike before Christmas’ has reached hundreds of U.S. stores

Starbucks' union says workers are walking off the job at some 300 — out of over 10,000 — stores across the U.S. as contract negotiations falter. The company urges it to return to the bargaining table.

American Airlines lifts ground stop that froze Christmas Eve travelers

American Airlines passengers across the U.S. endured a sudden disruption of service on Christmas Eve as a "technical issue" forced the airline to request a nationwide ground stop of its operations.

We needed comic relief in 2024. Here are 5 stand-up specials where we found it

Hasan Minhaj, Ronny Chieng, Mike Birbiglia, Hannah Einbinder and Michelle Buteau all delivered specials that cracked us up this year.

An Indian movie, loved abroad, is snubbed at home for Oscar submission

All We Imagine as Light explores the lives of working-class women in Mumbai and won the Grand Prix at Cannes. But it was deemed not Indian enough to submit to the Oscars.