Some Syrian refugees in Berlin ponder returning post-Assad, others call Germany home

BERLIN — The staff of two at the packed hole-in-the-wall Syrian restaurant Yarok in Berlin are swamped making hummus and falafel for a lunch crowd, but news of the downfall of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad has them both smiling.

Customer Razan Rashidi orders her tea with a celebratory phrase in Arabic, and the men manning the counter beam, telling her that on this day of liberation, tea for a fellow Syrian is free.

“It’s a day for celebration,” says Rashidi, who works as the executive director of the Syria Campaign, a human rights group based in Berlin.

Like many of the tens of thousands of Syrians who have settled in Berlin since Syria’s civil war began more than a decade ago, Rashidi was out late the night before, celebrating in the streets. “For me it was an amazing feeling just to be able to hug complete strangers and tell them, ‘Congratulations, Syria is ours and it does not belong to the Assad family!'”

For Rashidi, the liberation is personal. Up until this week, she undertook her human rights work as Laila Kiki, a pseudonym to protect herself from Syrian security officials. But today, the regime that routinely interrogated and harassed her before she fled Syria, is no more, and she is using her real name again for the first time in 17 years. She’s finally free to be herself, a feeling she thinks many Syrians are sharing this week.

“I want to go home,” she says, almost in tears as she thinks about returning to see family back in Syria. “I want to go visit for now, for sure, because it will take time to rearrange my life and my kids and all of that. But for sure, that’s my dream.”

The rebels’ swift seizure of power in Damascus over the weekend brought a sudden end to more than 50 years of rule by the Assad family. Assad’s reign, and the brutal civil war that began in 2011, sent more than 6 million people to seek refuge in other countries, in one of the world’s largest displacement crises, according to United Nations figures. Official German statistics count more than 970,000 of them living in Germany, where politicians are making their presence a political debate ahead of elections next year. Now, with change afoot in Syria, many of the exiles are considering visiting or moving back for good, although others feel settled in their new home in Europe.

At a Syrian restaurant in Berlin called Aleppo Supper Club, owner Samer Hafez says he hasn’t slept since he heard the news that the Assad regime was finished. His eyes red and tired, but he’s smiling, too. “Many Syrians I know haven’t yet really processed what’s just happened,” he says. “Even the idea of returning home to see family seems unreal. It’s like I’m in a dream.”

Ten years ago, Hafez was on a crowded boat in the Mediterranean Sea, fleeing his home country. He ended up in Berlin, a refugee, speaking no German, with no job and with barely any money in his pocket. “When I arrived to Germany, I had a to-do list,” Hafez remembers. “Year by year, I crossed off everything I needed to do to settle here and make this place my home: I started learning German and after three months, I had my first job. Then I met the woman who is now my wife. We had children. Then I opened my first restaurant. Then the second. And now the third. I just got my German passport, and when I had it in my hands, it was the first time I truly felt safe.”

Aleppo Supper Club now has three locations in Berlin and serves what some call the best hummus in town. Since making it to Germany, Hafez has been able to bring his mother and siblings over, too. His sister just graduated with a mechanical engineering degree and another sister is studying to become a doctor in Munich. Like many Syrians who arrived a decade ago, Hafez’s life is here.

German authorities have suspended approval of new Syrian asylum claims for now, as have several other countries. But some German politicians want to go further: They’re calling on the Syrians already settled in the country to leave.

This week on national television, Jens Spahn, a politician from the center-right Christian Democratic Union party, which is on track to win the most votes in the coming German election, made a public offer to Syrians. “The German government could charter flights for Syrians wishing to leave and give them a thousand euros for starter money,” Spahn said on the NTV network. “I’m thinking of all the young Syrian men here in Germany who undoubtedly wish to give their homeland a future and who want to help us make it possible for them to return to Syria voluntarily.”

Hafez finds this a strange notion.

“Home for me is here in Germany,” he says. “Sure I’m Syrian, but I’m also now a German. Every time I’m on vacation, I miss Berlin. I can’t stay away more than a couple of weeks. I’ve built a business and a life here. My family is here. Germany is my home. At least for now.”

Esme Nicholson contributed to this report.

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

The fall of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad is not only transformative for Syria. It’s also affecting Syrians who fled the country to escape the repressive regime. Many of them settled in Germany, where more than a million Syrians now live. As NPR’s Berlin correspondent, Rob Schmitz, reports, some are now weighing whether to go back.

ROB SCHMITZ, BYLINE: It is all smiles at the hole-in-the-wall Syrian restaurant Yarok in Berlin, where a staff of two dish out fresh hummus and falafel to a young lunch crowd. Razan Rashidi orders her tea with a celebratory phrase in Arabic. And the man at the counter beams, telling her that on this day of liberation, tea for a fellow Syrian is free.

RAZAN RASHIDI: It’s a day for celebration.

SCHMITZ: Rashidi is the executive director of The Syria Campaign, a human rights group based in Berlin. And she was out late the night before, celebrating with thousands of Syrians in the streets of Berlin.

UNIDENTIFIED CROWD: (Singing in Arabic).

SCHMITZ: Tens of thousands of Syrians live here in Berlin. Many, like Rashidi, ended up here after fleeing the violence in Syria more than a decade ago. Up until this week, Rashidi did her human rights work under the name of Laila Kiki. It was a pseudonym to protect herself due to the sensitivities of her human rights work. But now the regime that routinely interrogated and harassed her before she fled Syria is gone. And she says she’s using her real name again for the first time in 17 years – free to be herself, a tremendous weight lifted from her shoulders, like it is for all Syrians who live here, she says.

RASHIDI: They were celebrating in that protest. For me, it was an amazing feeling, just to be able to hug complete strangers and tell them, congratulations. Syria is ours, and it does not belong to the Assad family.

SCHMITZ: And while Rashidi has built a life here in Berlin, she says she’s yearning to return to Syria.

RASHIDI: I want to go home. I want to go visit for now, for sure, because it will take time to rearrange my life and my kids and all of that. But, for sure, that’s my dream. It has always been my dream.

SCHMITZ: Across town, at another Syrian restaurant, owner Samer Hafez oversees his kitchen crew chopping vegetables. His eyes are red and tired, but he’s smiling. He hasn’t slept since he heard the news that the Assad regime was finished.

SAMER HAFEZ: (Speaking German).

SCHMITZ: “Many Syrians I know haven’t yet really processed what’s just happened,” says Hafez. “Even the idea of returning home to see family seems unreal. It’s like I’m in a dream.” Ten years ago, Hafez was on a crowded boat in the Mediterranean Sea, fleeing his home country. He ended up here in Berlin, a refugee. He spoke no German, had no job and barely any money.

HAFEZ: (Speaking German).

SCHMITZ: “When I arrived to Germany, I had a to-do list. Year by year, I crossed off everything I needed to do to settle here and make this place my home,” he says. “I started learning German, and after three months, I had my first job. Then I met the woman who is now my wife. We had children. Then I opened my first restaurant, then the second, and now the third. I just got my German passport,” Hafez says. “And when I had it in my hands, it was the first time I truly felt safe.” Hafez’s Aleppo Supper Club now has three locations in Berlin and serves what some call the best hummus in town. Since making it to Germany, Hafez has been able to bring his mother and siblings over, too. His sister just graduated with a mechanical engineering degree, and another sister is studying to become a doctor in Munich. Like many Syrians who arrived a decade ago, Hafez’s life is here. And that’s why calls from some German politicians urging Syrians to return home feel a little strange to him.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

JENS SPAHN: (Speaking German).

SCHMITZ: This is politician Jens Spahn from the center-right Christian Democratic Union party, a party that will likely win the most votes in the coming German election. He said on television earlier this week that he proposes giving Syrians wishing to return to their home country 1,000 euros to go back. “I’m thinking of all the young Syrian men here in Germany who wish to give their homeland a future and who want to help us make it possible for them to return,” Spahn said. But Hafez shakes his head at this notion.

HAFEZ: (Speaking German).

SCHMITZ: “Home for me,” says Hafez, “is here in Germany. Sure, I’m Syrian, but I’m also now a German. Every time I’m on vacation, I miss Berlin. I can’t stay away more than a couple of weeks. I’ve built a business and a life here. My family is here. Germany,” says Hafez, “is my home – at least for now.”

Rob Schmitz, NPR News, Berlin.

As Time’s ‘Person of the Year,’ Trump outlines his top priorities in lengthy interview

In a wide-ranging and long interview, President-elect Donald Trump tells TIME Magazine his priorities for the first days of his second time at the presidency.

Missing American Travis Timmerman found wandering barefoot outside Damascus

The 29-year-old had last been seen in Budapest, Hungary. He said he was detained earlier this year after crossing into Syria on foot from Lebanon and held in prison until the fall of the Assad regime.

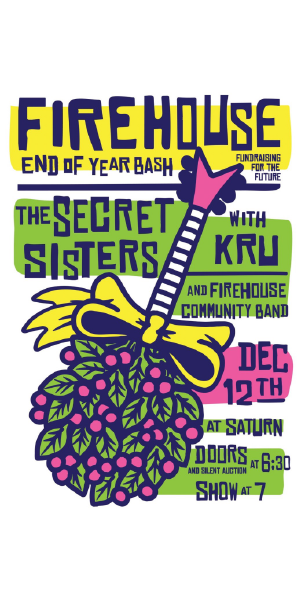

Girls Rock Birmingham gives future artists the spotlight

Picture a rock band and chances are it’s a bunch of men. But Girls Rock Birmingham, a local youth organization, is fixing that spotlight on girls by giving them the chance to take the stage to rock out.

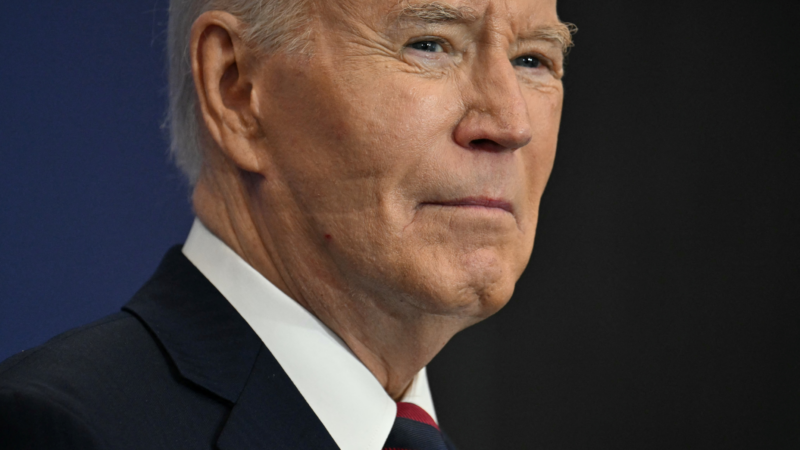

Biden commutes the sentences for 1,500 people, the largest act of clemency in a day

The 1,500 people had been serving long prison sentences that would have been shorter under today's laws and practices. They had been on home confinement since the COVID pandemic.

10 biographies and memoirs for the nonfiction reader in your life

These true stories range from a "meow-moir" of a Siberian cat to an exploration of what U.S. presidents do after the White House. Check out these nonfiction reads recommended by NPR staff and critics.

South Korea’s Yoon defends martial law decree as an act of governance

In an address to the nation, President Yoon Suk Yeol claimed the opposition-controlled parliament has been destroying the country's liberal democratic order.