Skin bleaching is terribly popular — and takes a terrible toll

Susan Anderson, age 52, sits in the corner of a sunlit waiting room at a dermatology clinic in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. Dark patches of skin, dotted with brighter pigments, surround her eyes and cover her cheeks.

“It used to be much worse,” she says, scrolling through pictures of her face on her phone, taken more than a year ago, when the blotches were raw and parts of her skin seared pink. Doctors who first saw her said it looked as if she had first-degree burns.

The first time Anderson used a skin whitening cream she was 12. Her stepmother gave it to her but didn’t tell her what it was for. “She never explained it to me,” she says. “I just felt it was a normal cream, and I was using them. I was naïve and I was vulnerable.”

The changes were subtle but her skin lightened. Within a few years, she moved on to a stronger product called Dermovate — at the time, the in-vogue skin whitening body lotion, recommended by her friends at high school. They knew most boys in her school were more interested in lighter skinned girls.

“Within one week, I started seeing changes. I started becoming fairer than I was,” she says, describing her euphoria at the transformation in her almond brown skin — not just on her face and hands as her friends used them but across her body. The newfound attention was instant, from boys who previously paid her little notice. “ I felt happy. I felt I was looking more beautiful.”

Initially she overlooked the reactions on her skin — freckles, blotches of uneven pigments, darkened knuckles. After she had to undergo an operation, doctors struggled to treat her as the whitening cream had eroded layers of her skin. “They sewed it, but the stitches were not holding,” says Anderson, pausing to gather herself. “I almost died at that point.”

By her mid-20s, she says, the visible reactions had become visceral as years of progressively stronger products had taken a toll. Blotches started to form and spread across her face. Friends recommended products, but they only aggravated it. “I was going crazy, using so many creams that people said would make it better but it never did.”

Dr. Vivian Oputa, an aesthetic dermatologist, observes: “A lot of people don’t realize how dangerous this practice has been. We’ve had several cases of newborns being bleached by their parents because they don’t want the kids to be dark.

“It’s just so, so unfortunate because of the pitfalls, the hazards, not knowing that the steroids that are used in addition to the bleaching agents, once you put them on your skin, they’re absorbed into your bloodstream. They can wreak havoc and damage internal organs, your kidneys, your liver. The steroids also thin the skin so the structural integrity of the skin is compromised. The blood vessels come to the surface. I mean, they’re visibly there.”

Skin lightening products represent a major global industry, with sales projected to nearly double to $15.7 billion by 2030. In Africa, nowhere is the practice more prevalent than in Nigeria. More than three-quarters of Nigerian women have used skin whitening products, according to the World Health Organization — compared to 27.1% on average in Africa. There’s a lesser but growing use of these products by young boys and men, according to businesses in the skin whitening industry.

Billboards advertising skin whitening products, with images of white or lighter skinned black women, are prevalent across Nigerian cities. Rooted in colonial-era beauty standards, the desirability of lighter skin tones, associated with higher socioeconomic status and attraction are reinforced across public and cultural life.

Zainab Bashir Yau, a licensed medical esthetician who founded a dermatology clinic, says a major challenge is a lack of regulation and the easy access to various pharmaceutical creams, containing potent steroids like clobetasol propionate, used to treat skin conditions like eczema but that are commonly known to lighten skin as well. “Some drugs should only be given on a prescription basis, but because our regulation is almost nonexistent, anyone can literally walk into a pharmacy and buy [skin bleaching products] without any prescription and use it for as long as they want.”

Another challenge is the prevalence of creams, soaps and skin whitening products with dangerous levels of potent steroids, which whiten skin tones. Exacerbating the dangers is a type of use, called “mixing,” Bashir Yau says. “Two people can be using the same product but they’re going to use it differently. One person may be using it alone. Another person may buy two or three bottles of that product, and mix it with another skin whitening product,” essentially heightening its intensity.

And the demand for bespoke products that are often more potent, tailored to achieve the specific skin tones customers desire, has become a key part of the skin whitening industry offers.

‘So white, so beautiful’

Twenty-nine-year-old Shafari Mansur is one of more than a dozen cosmetologists at the Sabon Gari market in Kano, northern Nigeria — the country’s third most populous city and a hub for skin whitening.

Several kiosks and small cube-like stores line the narrow walkways of the market, the storefronts plastered with posters of white and Arab women. Mansur’s store is one of the most popular, with small crowds of women waiting to be attended to. “Men use them too,” he says smiling, “but they don’t speak much. You don’t see them here but they call me and I fix something and send it to them.”

Inside, shelves display an array of beauty products, whitening soaps and creams, many of them variations of the same buzz words: Mirror White Whitening Lotion, Skin Beauty White, So White So Beautiful, Rapid White.

After a brief consultation with each customer, Mansur or one of his staff get to work. They mix various soaps or creams into plastic bowls, taken from the shelves. From unmarked plastic bottles, he adds milky solutions that he refers to as his “recipe.” Powders are added to the mix, cracked open from capsules of pills like doxycycline, an antibiotic that treats acne as well as infections. Mansur claims without evidence these ingredients help make the creams safe.

Some customers want other types of products, too. “Injections, like this one,” he says, holding up a small clear box of capsules of hyaluronic acid and hexapeptide, which are usually mixed with other whitening solutions. He doesn’t administer them himself, he says. Instead, he adds the serums to his creams or sells them to customers who go to other merchants to inject them.

But Mansur’s mixtures, like all whitening products, come with a catch. “If you stop using them, you turn back to Black,” he says. “God created you Black. Who can change you? Nobody.”

Swearing them off

Susan Anderson began treatment a year ago at DermaRX, the dermatology clinic founded by Zainab Bashir Yau that has doctors on staff. By the time she started, she was desperate. “I was at my end by that point. I had tried everything but nothing was working.” Her skin had thinned and become so itchy, it was a struggle not to scratch it. When she did, she says, it would bleed.

After almost 40 years of using whitening products, Anderson has sworn them off since February 2024. “It was actually very hard because when you stop, you go back to your normal way, the way you looked before but even worse.”

“Once you stop, your skin becomes darker than its original tone, and then it takes a while for it to return to your natural tone,” says the dermatologist Dr. Oputo. “They often become frustrated and go back to the bleaching.”

Within a few months, Susan Anderson’s skin tone gradually reverted back to what it used to be, but unevenly pigmented and thinned. But a year on, the improvement has been uplifting. “I’m so, so grateful,” she says. “It’s still difficult, I’m not as confident as I was, not going to parties or things like that but at least I feel better in myself.”

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Skin whitening is a major industry around the world, including in the U.S., but it is endemic in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country. It’s rooted in colonial-era beauty standards that see brighter skin tones as more desirable. The effects can be severe, and many people who use these products are unable to stop, as NPR’s Emmanuel Akinwotu reports.

SUSAN ANDERSON: I went through hell before I got myself again.

EMMANUEL AKINWOTU, BYLINE: Susan Anderson is a 52-year-old store assistant.

ANDERSON: I was helpless.

AKINWOTU: We met in the waiting room of a dermatology clinic in the capital, Abuja. Parts of her face looked seared with burns. Thick, dark patches of skin surrounded her eyes and covered her cheeks. Anderson started using skin whitening creams as a child, given to her by her stepmother.

ANDERSON: I think at the age of 12. She never explained to me. I just felt it was a normal cream, and I was using them. I was naive, and I was vulnerable.

AKINWOTU: When she was 15, a school friend recommended a stronger product used as a body lotion.

ANDERSON: Within one week, I started seeing changes. I started becoming more fairer than I was.

AKINWOTU: And how did it make you feel?

ANDERSON: I felt happy. I felt I was looking more beautiful.

AKINWOTU: Until it nearly killed her when she became pregnant.

ANDERSON: It was during delivery. I had a terrible cut.

AKINWOTU: She had a vaginal tear that doctors struggled to treat because the whitening creams had eroded layers of her skin.

ANDERSON: They sewed it, but the stitches were not holding. I almost died at that point.

AKINWOTU: And it took over a year for her to recover.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORN HONKING)

AKINWOTU: Skin whitening or skin bleaching is a major industry around the world, but especially in Nigeria. More than 77% of Nigerian women have used skin whitening products, according to the U.N. – the highest rate in Africa. One of the major markets in the country is the populous northern city of Kano.

(CROSSTALK)

AKINWOTU: At the Sabon Gari market are several small stores covered in posters and images of white and Arab women, which sell an array of skin whitening products.

Mirror White Whitening Lotion, Skin Beauty White, So White So Beautiful, Quick Action, Rapid White.

One of the store owners is 29-year-old Shafari Mansur.

SHAFARI MANSUR: Some person, they say they want bath salts. Some people, they say they want shower gel. Any one you want, we can do it for you.

AKINWOTU: He says most customers are interested in whitening creams and soaps, but some want other types of products, too.

MANSUR: Injection, like this one.

AKINWOTU: He shows me a box of small, clear capsules of hyaluronic acid and hexapeptide, used for injection. He says he doesn’t administer them himself.

MANSUR: But me, I’m not doing it. It’s not good.

AKINWOTU: Instead, he says, he uses the serums to mix bespoke creams and soaps for customers. Traders like Shafari mix a cocktail of various whitening products with self-made solutions…

(SOUNDBITE OF MIXING)

AKINWOTU: …Stirring them in plastic bowls in their stores. But there’s a catch with all whitening products, he says – they only work if you keep using them.

MANSUR: If you stop using it, you turn back to you are Black. God create you Black. Who can change you? Nobody.

AKINWOTU: He said God created you Black, and no one can change it. So when you stop, your skin reverts back within weeks, but with damage.

ZAINAB BASHIR: People that bleach their skin, it’s like an addiction.

AKINWOTU: Zainab Bashir is Susan Anderson’s doctor in Abuja. She founded DermaRx, a dermatology clinic. She said there is very little regulation of skin whitening products.

BASHIR: Anyone can literally walk into a pharmacy, buy it without any prescription, and use it for as long as they want.

AKINWOTU: The products have been linked to higher rates of skin cancer, and Nigeria’s government said it was considering new regulations on skin whitening products. After her medical scare, Susan Anderson briefly stopped using the whitening creams, but then she started again…

ANDERSON: It was actually very, very hard for me to stop using them.

AKINWOTU: …And continued for decades, while battling severe reactions and burns. She felt more and more isolated as the side effects worsened.

ANDERSON: I couldn’t get a job. And I also lost a man whom I was dating, that I was supposed to get married to, because he said we cannot present me to his family.

AKINWOTU: She eventually found work as a store assistant, and during one of her shifts last year, she met Zainab Bashir, who brought Anderson to her clinic.

ANDERSON: She said I shouldn’t worry – that she’s going to help me out. And I was really very grateful to her.

AKINWOTU: And after losing hope, she finally found the help she needed. Emmanuel Akinwotu, NPR News, Abuja and Kano.

Italian fashion designer Valentino dies at 93

Garavani built one of the most recognizable luxury brands in the world. His clients included royalty, Hollywood stars, and first ladies.

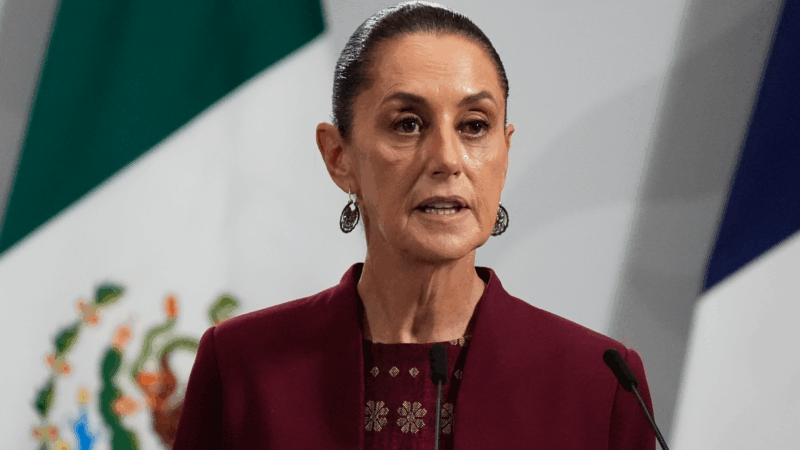

Sheinbaum reassures Mexico after US military movements spark concern

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum quelled concerns on Monday about two recent movements of the U.S. military in the vicinity of Mexico that have the country on edge since the attack on Venezuela.

Trump says he’s pursuing Greenland after perceived Nobel Peace Prize snub

"Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize… I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace," Trump wrote in a message to the Norwegian Prime Minister.

Trump has rolled out many of the Project 2025 policies he once claimed ignorance about

Some of the 2025 policies that have been implemented include cracking down on immigration and dismantling the Department of Education.

U.S. lawmakers wrap reassurance tour in Denmark as tensions around Greenland grow

A bipartisan congressional delegation traveled to Denmark to try to deescalate rising tensions. Just as they were finishing, President Trump announced new tariffs on the country until it agrees to his plan of acquiring Greenland.

Can exercise and anti-inflammatories fend off aging? A study aims to find out

New research is underway to test whether a combination of high-intensity interval training and generic medicines can slow down aging and fend off age-related diseases. Here's how it might work.