Seeking to heal the country, Jimmy Carter pardoned men who evaded the Vietnam War draft

When President Jimmy Carter was inaugurated in 1977, he wasted little time fulfilling one of his most controversial campaign promises: pardoning those who evaded the Vietnam War draft.

Carter issued Proclamation 4483 on his first full day in office, less than two years after the end of what was then America’s longest war.

The new commander in chief was hoping to heal the divisions left by the conflict, but the move also drew criticism from some who believed it was too lenient toward the men who had sidestepped military service during the war.

It’s one of the defining presidential moments for Carter, who died on Dec. 29 at age 100.

Anti-war activists had urged pardons for draft violators

Carter himself had served in the armed forces before entering political life. He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1946 and rose to the rank of lieutenant.

But during the Vietnam War — and especially as public sentiment turned against the conflict — young men made efforts to avoid the draft.

There were legal ways to avoid the draft, such as going to college or having a medical condition that exempted you from military service. And there were illegal ways, such as fleeing to another country.

Absconding abroad required money. The majority of enlisted men who served in Vietnam came from working-class backgrounds.

As America’s involvement in the war wound down, the public was faced with the issue of what to do about those men who had eluded military service and were now in legal limbo.

David Kieran, a professor of military history at Columbus State University who has written about the Vietnam War, said Americans were divided on the question of whether to punish draft evaders for violating the law or forgive them to help the American public move on from the war.

“Were these people who had not lived up to their civic duty … and had failed to serve their country when their country called?” Kieran said. “On the other hand, there were people who argued these were people who had taken a moral stand against an unjust war.”

During the 1976 presidential campaign, Carter said it was critical for the country to unite after the war and vowed to pardon all the men who had evaded the draft.

“I think that now is the time to heal our country after the Vietnam War,” he said during a televised debate.

His Republican opponent, then-President Gerald Ford, didn’t support an across-the-board pardon. During his time in the White House, Ford started a program granting amnesty to some men who had evaded the draft during the Vietnam War in exchange for 24 months of public service.

Carter made good on his promise — and got flack from both sides

Carter won, and after he was inaugurated he issued a pardon for certain people who “violated the Military Selective Service Act by draft-evasion acts or omissions committed between August 4, 1964 and March 28, 1973.”

The pardon meant that the thousands of men who skirted military service and either went underground or fled abroad to countries such as Canada and Sweden wouldn’t face criminal charges. It didn’t apply to people who had begun military service and then deserted.

The move was pilloried by members of the military and conservative politicians, who said it was an insult to those who had gone to Vietnam. Sen. Barry Goldwater, a Republican from Arizona, said the pardon was “the most disgraceful thing that a president has ever done,” The Washington Post reported at the time.

Yet others said Carter’s action didn’t go far enough.

The American Veterans Committee praised the pardon but said it should have also included deserters and those who were given less-than-honorable discharges, categories that were disproportionately represented by “minority and less advantaged groups in our society.”

In the years that followed, Kieran said, conservatives continued to view liberals as apologizing for the Vietnam War, with Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan declaring in 1980 that America had fought for a “noble cause” in the country.

But decades later, Carter still defended the pardon as “the right thing to do” and saw it as an extension of the partial amnesty program undertaken by the Ford administration.

“I think, in that sense, [Carter] is seen as having made a good-faith effort,” Kieran said, “to address an issue that had been a fairly significant one in American life for nearly a decade by the time he becomes president, and really sought to find a way to help the country heal after Vietnam.”

WBHM wins 3 ABBY Awards

WBHM 90.3 FM won 3 ABBY Awards for 2025 – a prestigious honor given annually by the Alabama Broadcasters Association. The ABA presented the awards Saturday, April 5 in Birmingham.

Most Americans want to read more books. We just don’t.

When we worry about the declining rates of literacy and a lack of reading skills, it's often about children. But how often are adults reading these days? And what are we reading? A new NPR/Ipsos poll finds out.

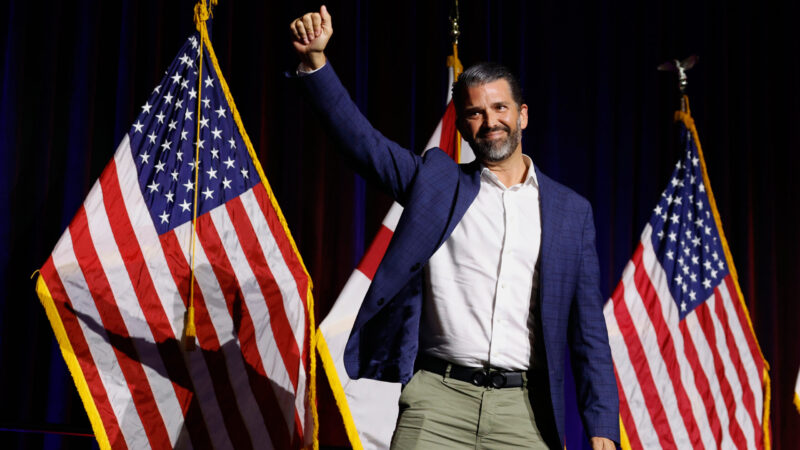

In conservative Alabama, Republicans are cheering for Trump – with some quiet concerns and caveats

Alabama Republicans cheered President Donald Trump and his agenda at a GOP party the day he imposed tariffs and sent stock markets tumbling worldwide. But there were signs of a more cautious optimism and some worried whispers over Trump’s sweeping tariffs, the particulars of his deportation policy and the aggressive cuts by his Department of Government Efficiency.

The artist behind ‘the worst’ Trump portrait defends her work

The painting, which was commissioned by Republicans, has hung in Colorado's state Capitol since 2019. Trump follows other U.S. presidents who weren't flattered by their depictions.

Are UAB officials mum about grant cuts because they fear a spiteful president?

Cuts to federal research grants could cost UAB $70 million a year, leading to layoffs and economic impacts beyond the campus. Some faculty and area leaders want UAB to be more vocal against the Trump administration cutbacks.

The (artificial intelligence) therapist can see you now

Many AI products claim to deliver mental health therapy, but with little quality control. But new research suggests with the right training, AI can be effective at helping people.