Russia targets Ukraine’s energy grid as winter sets in. Here’s how one plant copes

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series on Ukraine’s energy industry under attack. Click here for a photo essay from Ukrainian coal country.

AT A UKRAINIAN POWER PLANT — Donning hard hats and thick uniforms, Lesia and Nadia sweep pulverized concrete out of a dark, broken room inside the thermal power plant where they’ve worked for years.

The women normally would be operating the conveyor belt that delivers coal, Ukraine’s primary fuel source, to the plant’s furnace. Instead they are clearing the conveyor belt’s remains after a Russian missile attack earlier this year.

“I did not think this would ever be a dangerous job,” Nadia says.

“We love our work,” Lesia adds, “but we have a constant feeling of fear.”

Lesia remembers the day of the attack, how everyone ran to the bomb shelter as the air raid siren blared.

“We stayed there a long time, like three hours,” she says. “We hoped the missile would hit somewhere else. But it came right at our plant. We heard the explosions from the shelter.”

For months now, she and her colleagues have returned to the plant every day to fix it and help keep the lights and heat on as winter sets in.

A new reality

This plant is owned by DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy supplier. It says Russia has attacked its facilities nearly 200 times since the Russian invasion in February 2022. Much of the company’s infrastructure has been damaged or destroyed.

The company requested that NPR not disclose either the plant’s location or the last names of workers to avoid giving Russian forces any information that might help target the energy company workers and facilities.

Russian strikes on Ukraine’s energy grid have been so frequent this year that they have knocked out more than half of Ukraine’s energy-generating capacity. On Nov. 28, after Russia’s 11th mass attack on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure this year, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to strike again with a new ballistic missile that has nuclear capabilities.

To cope with the attacks, Ukraine has turned to emergency imports of electricity from neighboring countries and enacted rolling blackouts. Homes and businesses have backup generators on hand.

In Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, Yevhen Hutman, a 40-year-old investment analyst for startups, says most people are prepared for power outages.

“Nobody wants this tough winter,” he says. “We have our power banks. We have all the stuff we need to, for example, work from home. But yeah, it’s tiring.”

Anastasiia Shalukina, a 25-year-old nonprofit worker, has backup power at home and carries a tourniquet when she goes out due to frequent attacks.

“When I’m going abroad, when I hear fireworks,” she says, “I [get] a panic attack.”

“We had to get used to it”

The power plant NPR is visiting has already been attacked several times, according to plant manager Oleksandr.

“There was a lot of panic the first time,” he says. “We are civilians, we aren’t trained to deal with this. After the first couple of strikes, though, it became clear that this was not going to end, and we had to get used to it.”

Oleksandr walks us through the vast grounds of the plant on a chilly, rainy day. Everyone is busy repairing something or clearing parts of buildings damaged by Russian strikes. There are teams on cranes, and crews on the muddy ground.

Vasyl, another manager, who is in charge of repairs, sidesteps a pile of crushed bricks and says that his team had only been trained for routine maintenance.

“Now they mainly fix or replace equipment damaged by missiles,” he says. “Boilers, turbines, generators, and also equipment that provides fuel supply. All this needs to be restored.”

His staff, he says, is learning as they go, following safety precautions in case something collapses.

Nearby, another crew in heavy protective gear is repairing the plant’s outdoor switchyard, which connects the station to the transmission network. The crew’s leader, Andriy, asks NPR’s team to stay back to avoid getting electrocuted.

“We restored and replaced all those wires there,” he says, pointing. “You can see the new ones. Everything was damaged when the missile exploded overhead.”

Aided by allies

This scene is playing out at power plants all over Ukraine. Energy officials say the damage likely would have been much worse if Ukraine didn’t have support from allies like the European Union and the United States.

In October, EU lawmakers approved loaning Ukraine 35 billion euros ($38 billion), financed by interest from frozen Russian central bank assets. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that one of his top priorities was to rebuild Ukraine’s energy network.

The EU and the U.S. have also donated air defense systems that shoot down Russian drones and missiles.

Meanwhile, Ukrenergo, Ukraine’s state-run energy company, has used materials like concrete and rebar supplied by the U.S. Agency for International Development to build shelters shielding the most critical energy equipment. USAID Administrator Samantha Power, who has traveled to Ukraine several times since Russia’s 2022 invasion, examined one of these structures during a visit in October.

“What we have learned over this very difficult wartime period is that there is no panacea for Putin’s brutality, no inoculation,” she told NPR then.

“But if something slips past air defense, if the Ukrainians are not able to shoot down a drone or a missile, this type of physical protection — the concrete, the rebar, the mesh — has made a profound difference in keeping energy online,” she added.

It’s not clear the U.S. will continue supporting Ukraine once the Trump administration takes office. President Biden is trying to push through as much Ukraine aid as possible before his term ends.

In a September report by the Paris-based International Energy Agency, Ukraine had already lost about 70% of its thermal generation capacity since this spring due to Russian strikes or occupation. (The Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, which generated about a quarter of Ukraine’s electricity supply before Russia’s 2022 invasion, is under Russian control.) DiXi, a Ukrainian energy analytics group, predicts blackouts could last up to 20 hours a day if this winter is especially harsh.

A Sisyphean task

Meanwhile, the EU and U.S. recently earmarked a combined $112 million in energy equipment and building for DTEK, the private Ukrainian power company. The aid is supposed to help Ukraine continue to weather Russian strikes on energy infrastructure, the most recent of which was on Nov. 17.

“No country in modern times has faced such an onslaught against its energy system,” DTEK CEO Maksym Timchenko said in a statement. “But with the help of our partners we continue to stand strong against Russia’s energy terror.”

Across Ukraine, workers continue the seemingly Sisyphean task of repairing power plants after each Russian attack.

At the DTEK plant visited by NPR, shattered windows are patched up with tarp. Buildings are scorched, with holes caused by missile shrapnel. Crews instead are focused only on fixing the equipment the plant needs to operate.

Petro, an amiable, bearded mechanic, is working with a team replacing the pipes pumping out coal waste.

“We have to finish before the frost, sooner even,” he says. “As soon as possible.”

At least before the next Russian strike.

Producers Hanna Palamarenko and Volodymyr Solohub contributed to this report.

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

In Ukraine, at least a million people were left without power today after another Russian bombardment of the already damaged energy grid. Russian leader Vladimir Putin said it was a comprehensive strike in response to Ukraine’s use of U.S.-made long-range missiles inside Russia. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy says Russia used highly destructive cluster munitions in its overnight attack. In Kyiv, producers Hanna Palamarenko and Volodymyr Solohub found that people have gotten used to days like this one.

YEVEN HUTMAN: We have this big missile attacks every day, every week, every month.

SHAPIRO: Yeven Hutman (ph) says it may sound fatalistic, but his feelings are just not as sharp about this attack as they were for the first ones nearly three years ago now.

HUTMAN: Nobody wants this tough winter, but we are all prepared in some way. Of course, we have our power banks. We have all the stuff that we need to – for example, to work from home and other things. But yeah, it’s tiring.

ANASTASIA SHALUKINA: The guys on the front line – they feel worse, so we have nothing to complain about, and it’s reality.

SHAPIRO: Anastasia Shalukina (ph) says she has decent Wi-Fi and some backup power at home. Although, when she goes out, she carries a tourniquet. She understands she has been desensitized to some daily realities of war but not all of them.

SHALUKINA: It’s very scary to say that it’s become, like, a normal and regular thing because when I’m going abroad, when I hear the fireworks, I – like, I got the panic attack.

SHAPIRO: Even before today, previous attacks on energy infrastructure meant that millions of Ukrainians were already facing a winter with up to 20 hours of electricity cuts per day. And to help keep the lights on, workers are rushing to repair damaged power plants before the harsh frost sets in. NPR’s Joanna Kakissis recently visited one of those plants.

(SOUNDBITE OF SHOVEL SCRAPING)

JOANNA KAKISSIS, BYLINE: Two women in hard hats scrape pulverized concrete out of a dark, broken room. They’re inside a thermal power plant, where they’ve worked for years. Lesia says she should be operating the conveyor belt that delivers coal – Ukraine’s main fuel source – to the plant’s furnace. But earlier this year, a Russian missile hit the plant.

LESIA: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “The attack really shook everything up,” Lesia says. “Look at all this mess. That used to be the conveyor belt.”

She remembers everyone running to the bomb shelter the day of the attack.

LESIA: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “And we stayed there a long time, like, three hours,” she says. “We hoped the missile would hit somewhere else, but it came right at our plant. We heard the explosions from the shelter.”

The attack left Lesia in a constant state of fear, but she and her colleagues have returned to the plant every day for months to fix it. This plant is owned by DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy supplier. Russia has struck all six of DTEK’s thermal power plants this year. At the request of the company, NPR is not disclosing the plant’s location or the last names of its workers for security reasons.

OLEKSANDR: (Non-English language spoken).

KAKISSIS: Oleksandr manages the plant. He says Russia has already attacked it several times. He worries about morale.

OLEKSANDR: (Non-English language spoken).

KAKISSIS: “There was a lot of panic after the first strike,” he says. “We are civilians. We aren’t trained to deal with this. After the first couple of attacks, though, it became clear that this was not going to end, and we had to get used to it.”

We walk through the plant on a cold, rainy day. There are teams on cranes and crews on the ground. Birds rest on heaps of rubble and twisted metal.

VASYL: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: A manager named Vasyl steps over a muddy pile of bricks. He’s in charge of repairs.

VASYL: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “Boilers, turbines, generators, and also equipment for fuel supply,” he says, “all this needs to be restored.”

VASYL: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: He says workers are learning how to do this on the fly, following safety precautions in case something collapses.

(SOUNDBITE OF MACHINERY HUMMING)

KAKISSIS: Outside, a crew is working on the switch yard, which connects the plant to the transmission network. They wear heavy protective suits to prevent electrocution. Andriy is the crew’s leader.

ANDRIY: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “We replaced all those wires,” he says. “Over there, you can see the new ones. Everything was damaged after the missile exploded.”

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: (Non-English language spoken).

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: (Non-English language spoken).

KAKISSIS: This is the scene at power plants all over Ukraine. Energy officials say the damage would’ve been much worse without support from the European Union and the U.S. Ukraine’s allies have donated air defense systems to shoot down Russian drones and missiles.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: The heart of the substation because it…

KAKISSIS: The U.S. Agency for International Development also supplied raw materials to the Ukrainians for protective measures. Ukraine’s state energy company, Ukrenergo, used materials like rebar and concrete to build shelters around critical equipment. USAID administrator Samantha Power examined one of these shelters during an October visit to Ukraine.

SAMANTHA POWER: What we have learned over this very difficult wartime period is there is no panacea. But if something slips past air defense, if the Ukrainians are not able to shoot down – whether it be a drone or a missile – this physical protection has made a profound difference in keeping energy online.

(SOUNDBITE OF STEAM HISSING)

KAKISSIS: And so has the seemingly Sisyphean task of fixing energy equipment after every Russian strike. At the DTEK power plant we visited, crews are working overtime. A mechanic named Petro is replacing pipes that pump out coal waste.

PETRO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: “We just have to finish before it gets really cold,” he says. “Sooner even – as soon as possible, at least,” he says, “before the next Russian missile strike.”

Joanna Kakissis, NPR News, reporting from a power plant in Ukraine.

Winter Storm Cora brings cold and snow to the Southern U.S.

A major winter storm is expected to be the biggest in years as cold air moves in from the Arctic bringing snow and frigid temperatures across 20 Southern States.

Trump loses Supreme Court appeal to block hush-money sentencing

This was the only one of Trump's criminal charges to reach and complete a trial, making him the first former or future U.S. president to be convicted of criminal charges.

The Gulf South needs more sexual assault nurse examiners. Is teleSANE the answer?

While some see telemedicine as a useful tool to help provide care to sexual assault survivors, others believe it's not enough to solve the nursing shortage.

Lebanon chooses a new president after two years without one

Lebanon's parliament chose the head of the country's armed forces, Joseph Aoun, to be its next president, a post that's been vacant since October 2022.

Powerful winds fueling the California wildfires are expected through Friday

Red flag warnings are in effect for parts of Los Angeles and Ventura counties, as the National Weather Service warns that powerful winds and low humidity will increase the risk of fire.

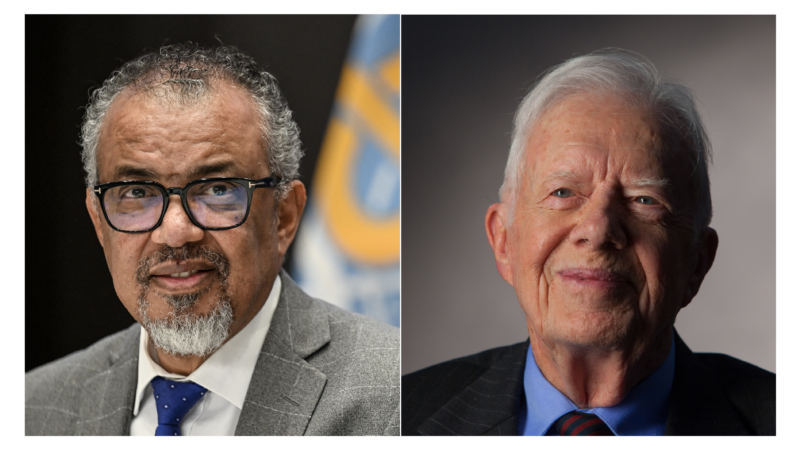

World Health Organization head on bond with Jimmy Carter: ‘I consider him my mentor’

The World Health Organization leader worked with Carter for 20 years to fight the world's "neglected" diseases. After attending Carter's funeral, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus shared memories.