Richer countries are starting to pay poorer ones for climate change damages

It was 2 a.m. when floodwaters started pouring into Christopher Bingala’s house. Cyclone Freddy, the longest-lasting tropical cyclone ever recorded, brought a deluge of rain to southern Malawi in 2023. He managed to get his six kids to higher ground but lost his house and livestock.

As a subsistence farmer, Bingala didn’t have the resources to start over. But then he got a payment of about $750, which he used to build his family a new house.

The payment is one of the first examples of “loss and damage” compensation, a new kind of funding specifically for climate change-related disasters. Low-income countries are bearing the brunt of more intense storms and droughts but have done little to produce the pollution that’s heating up the planet. So last year, wealthier countries agreed to create a fund specifically to pay for the damages from climate change.

So far, about $720 million has been pledged from countries, like the European Union, U.S. and United Arab Emirates. But climate experts warn that with hurricanes and floods only getting worse, that amount will fall far short.

At the COP29 climate summit underway in Baku, Azerbaijan, countries are negotiating how much is owed to developing nations, as part of a larger “climate finance” package that includes loans and investments.

“We just hope that the global north and the nations whose economy is fueled by the emissions – they come to the plate and take up their responsibility to look at what they’re causing us,” says Philip Davis, prime minister of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas.

Finding a way to start over

The havoc from Cyclone Freddy was widespread across several countries, displacing 650,000 people from their homes in Malawi alone. The country received six months of rain in just six days.

After their house collapsed in the floodwaters, Bingala and his family took refuge on higher ground, but the situation quickly deteriorated. They started running out of food.

“We got to a point where we would eat meat from animals that had died from the cyclone because we lacked food,” Bingala says. “This was a very difficult moment in my life.”

Along with thousands of others, he and his family were relocated to temporary camps. But as a small-scale farmer and fisherman, Bingala had no safety net to fall back on. Then he received the cash payment, which allowed him to move to a new village and build a better house. There are still challenges – Bingala is still trying to get his kids back in school and he’s hoping to get a few livestock again. But he’s glad his family is living in a less flood-prone region.

“They are better off here because they are not in danger of the water challenges we had back in Makhanga,” Bingala says. “This is a dry and upper land, so my children are ok and they’re happy. They’re living a happy life.”

Piloting a system to pay damages

The payment Bingala received came from the government of Scotland, the first country to dedicate funding specifically for loss and damage. The funds have gone to several countries so far. In Malawi, they were given out by GiveDirectly, a non-profit that specializes in providing cash grants to those in need with no strings attached.

About 2,700 families got payments of around $750, which can be equivalent to two years of income in Malawi. Many used the money to rebuild homes, while others invested in seeds, fertilizers and livestock, or putting their kids back in school.

“Low-income households in low-income countries have far less protections from extreme events,” says Yolande Wright, vice president of partnerships at GiveDirectly. “They may not have any sort of insurance. There may not be any insurance products available, even if they wanted to buy them.”

The program in Malawi is a pilot, in a sense, for a larger system to pay for loss and damage. Last year, countries agreed to create the fund as a way to compensate lower-income countries, which have low greenhouse gas emissions overall. Almost half of all emissions since the Industrial Revolution have come from the U.S. and Europe.

“The very poor, low-income households in Malawi have contributed the least to the climate problem,” Wright says. “Many of them are not connected to electricity. They don’t own a car or even a motor bike.”

A ballooning need for loss and damage funding

Increasingly severe hurricanes, storms and droughts pose a massive financial burden on developing countries, especially those already in debt. In the Bahamas, Prime Minister Davis says his country’s national debt went up after Hurricane Dorian hit in 2019.

“For me to recover and rebuild, I have to borrow,” Davis says. “Forty percent of my national debt could be directly attributed to the consequences of climate change.”

So far, the majority of $720 million pledged for loss and damage has yet to start flowing. At the COP29 summit, countries finalized the paperwork to create the fund, which will be housed at the World Bank. The fund’s guidelines have yet to be set up, like determining which countries will receive funding and for what kinds of damages.

Many low-income countries have argued the funding should go to more than just disaster recovery. Some could be used to relocate villages in the path of sea level rise, or to compensate countries for the loss of important cultural sites or ecological resources, like coral reefs.

The need for loss and damage funding is only expected to balloon as disasters get more extreme. One recent study found it will reach $250 billion per year by 2030. Davis says he hopes richer countries will contribute more in “enlightened self-interest,” since many humanitarian crises do not stay confined to country borders.

“If they do nothing, they will be the worst for it,” Davis says. “When my islands are swallowed up by the sea, then what do my people do? They’ll either become climate refugees or they’ll be doomed to a watery grave.”

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

The wealthiest countries are responsible for most of the pollution that causes climate change. So should they pay other countries for the damages, like intense storms? That’s a key question at the COP29 negotiations going on in Azerbaijan this week. As Lauren Sommer reports from NPR’s Climate Desk, the first payments are starting to go out.

LAUREN SOMMER, BYLINE: Cyclone Freddy was a monster storm, the longest-lasting tropical cyclone ever recorded. In 2023, it slammed into the east coast of Africa. It was 2 in the morning when floodwater started pouring into Christopher Bingala’s house. He lived in a small village in southern Malawi with his six kids.

CHRISTOPHER BINGALA: (Through interpreter) My house was filled with water. The whole house was filled up with water, so the house eventually collapsed.

SOMMER: His livestock got washed away, but he managed to get his kids to higher ground. Food quickly became scarce.

BINGALA: (Through interpreter) We got to a point where we would eat meat from animals that have died from the cyclone because we lacked food. And this was a very difficult moment in my life.

SOMMER: The government eventually moved him and thousands of others to a temporary camp. As a subsistence farmer, he didn’t have the resources to start over. But then he got a cash payment of about $750. He used it to build a new house for his family in a village that’s less prone to flooding.

BINGALA: (Through interpreter) They are better off here because they’re not in danger of the water challenges that we had back in Mahkanga (ph). This is a dry and upper land, so my children are OK, and they are happy. They are living a happy life.

SOMMER: The cash payment Bingala got is from a new pot of money specifically for disasters that are being made worse by climate change. It’s known as loss and damage. The funds came from the government of Scotland and were given out by the nonprofit GiveDirectly. That’s where Yolande Wright works. She says countries like Malawi are suffering some of the worst damage from a problem they did little to cause.

YOLANDE WRIGHT: The very poor, low-income households in Malawi have contributed the least to the climate problem. Many of them are not connected to electricity. They don’t own a car or even a motorbike.

SOMMER: Almost half of all the greenhouse gas emissions since the industrial revolution have come from the United States and Europe. So a year ago, they agreed to create a loss and damage fund to compensate more vulnerable countries. Wright says the program in Malawi is one of the first pilots. About 2,700 people used it for things to restart their lives.

WRIGHT: From basic agricultural material – seeds, fertilizer – to livestock. They’ve also invested in getting their children back into school.

SOMMER: Richer countries have agreed to supply more of this loss and damage funding. Around $720 million was pledged so far, but much more will be needed. One study found the amount will be $250 billion per year by 2030. It’s why many vulnerable countries are pushing for a bigger commitment at this year’s climate negotiations, which are now underway. Philip Davis, prime minister of the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is one of them.

PRIME MINISTER PHILIP DAVIS: We just hope that the Global North and the nations whose economy is fueled by the emissions – they come to the plate and take up their responsibility to look at what they’re causing us.

SOMMER: Like many island nations, Davis says the cost of hurricanes and rising sea levels will be insurmountable for The Bahamas. And richer nations will be affected by that, too.

DAVIS: If they do nothing, they will be the worst for it. When my islands are swallowed up by the sea, then what do my people do? They either become climate refugees, or they’ll be doomed to a watery grave.

SOMMER: The impacts of climate change, he says, don’t stay within borders.

Lauren Sommer, NPR News.

Party City files for bankruptcy and plans to shutter nationwide

Party City was once unmatched in its vast selection of affordable celebration goods. But over the years, competition stacked up at Walmart, Target, Spirit Halloween, and especially Amazon.

Sudan’s biggest refugee camp was already struck with famine. Now it’s being shelled

The siege, blamed on the Rapid Support Forces, has sparked a new humanitarian catastrophe and marks an alarming turning point in the Darfur region, already overrun by violence.

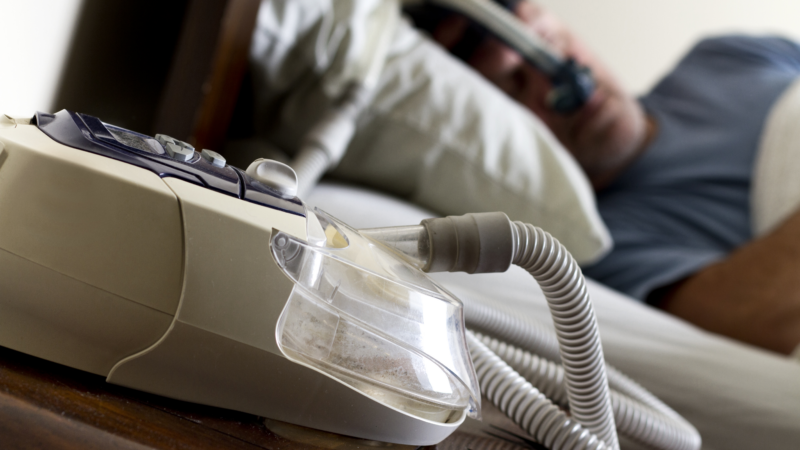

FDA approves weight loss drug Zepbound to treat obstructive sleep apnea

The FDA said studies have shown that by aiding weight loss, Zepbound improves sleep apnea symptoms in some patients.

Netflix is dreaming of a glitch-free Christmas with 2 major NFL games set

It comes weeks after Netflix's attempt to broadcast live boxing between Jake Paul and Mike Tyson was rife with technical glitches.

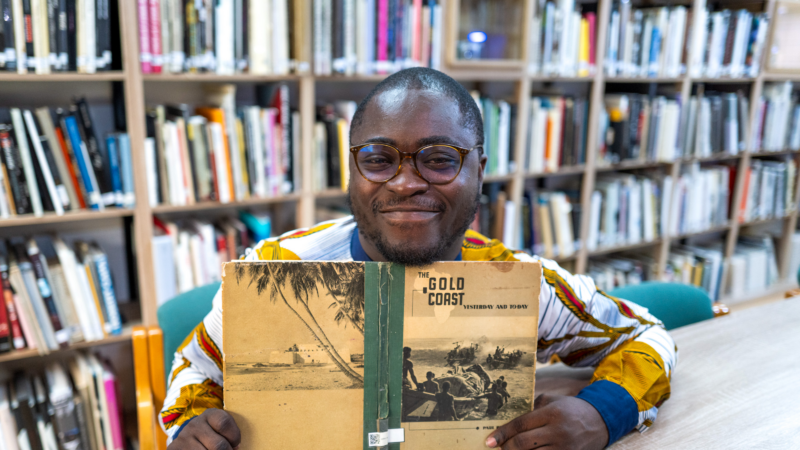

Big dreams: He’s the founder of a leading African photobook library

Paul Ninson had an old-school, newfangled dream: a modern library devoted to photobooks showing life on the continent. He maxed out his credit cards, injured his back — and made it happen.

Opinion: The Pope wants priests to lighten up

A reflection on the comedy stylings of Pope Francis, who is telling priests to lighten up and not be so dour.