Retraining a brain addicted to cocaine, one prize at a time

A thin, shy 24-year-old arrived on time, excited for his weekly appointment at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center. It’s a stark contrast to the day four years ago when he broke down in a doctor’s office crying, confused, slipping into withdrawal and questioning whether he wanted to live.

“I didn’t know what I was using, what addiction was, what was happening to my body,” V said. “I was scared ‘cause I couldn’t stop.”

WBUR agreed to use his first initial to avoid harming his job prospects. He hopes to become a first responder and help people like himself, struggling, on the streets.

The doctor sent V to see Rosali Santiago, a nurse in the health center’s addiction treatment clinic. Santiago explained that the fake pain pills V bought on the street to help him cope with anxiety and depression contained fentanyl. That meant he was addicted to opioids. Santiago helped V start Suboxone, an opioid treatment medication.

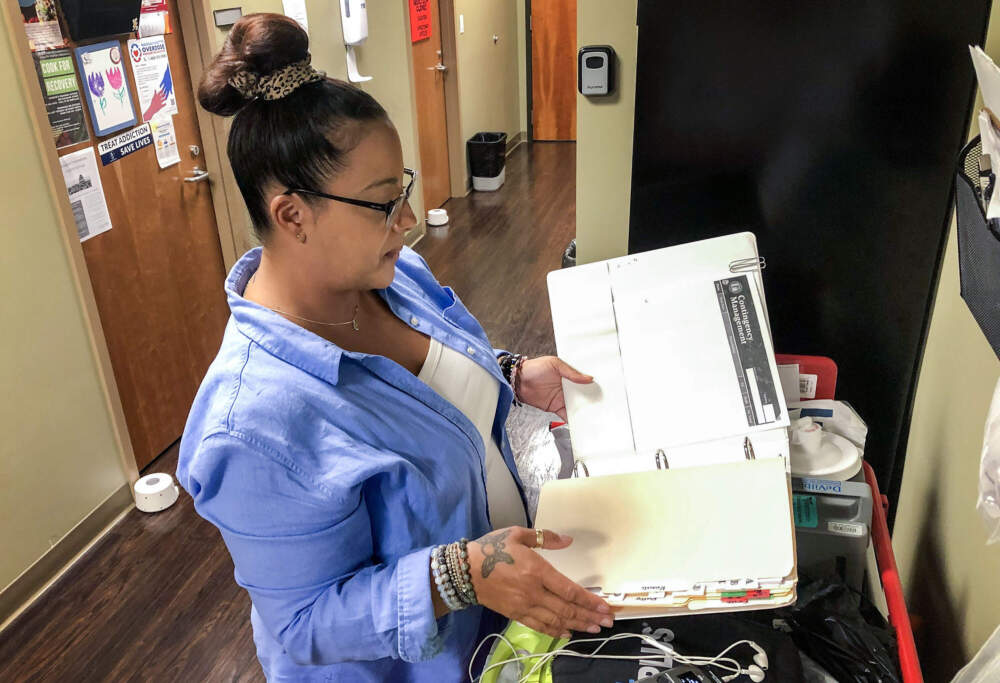

V was also addicted to cocaine. For that, Santiago had nothing to offer. There are no medications approved for patients with an addiction to cocaine, or other stimulants such as methamphetamine. But there is another approach that more than 30 years of research shows is effective. It turned out Santiago’s boss had been reading up on that treatment — called “contingency management” — and would soon win a grant to start a pilot program.

Retraining the brain

The approach’s nerdy name is linked to psychologist B.F. Skinner’s theories about how behavior can be shaped through positive reinforcement. In contingency management, patients set frequent, often weekly, goals. If they achieve them, patients receive rewards.

“People are looking for that burst of dopamine in the brain. The same neuro-biology that drives substance use can drive recovery.”

Dr. Brian Hurley

V’s early goal was to stay off cocaine for a week. If a drug test came back with no trace, V would receive a prize. Studies show that reinforcing abstinence in this manner doubles a patient’s chances of staying off drugs.

Contingency management uses some decidedly low-tech tools. V demonstrated, spinning a clear plastic cylinder that might spit out bingo numbers or winning raffle tickets.

Slips of blue paper fluttered through the air inside the tube. Each offered a prize ranging from a pat on the back, to art supplies, gift cards or a pair of headphones. Anticipation grew as one slip dropped onto a tray.

V picked it up and read, “Good job.” That meant he could get a sticker with those or similar words or on it. V laughed — no sign of disappointment.

“No, not all,” V said. “Because next time you do another goal, you get another chance, and who knows, you might get a large prize. It makes you feel even happier.”

The American Society of Addiction Medicine says contingency management should be standard treatment for patients addicted to stimulants like cocaine. Society president, Dr. Brian Hurley, explained that contingency management redirects a patient’s search for gratification from drugs — to abstinence.

“People are looking for that burst of dopamine in the brain,” Hurley said. “The same neuro-biology that drives substance use can drive recovery.”

The VA Health System offers contingency management treatment, but this approach is not typically covered by private or public insurance programs. So the primary, evidence-based stimulant treatment option has not been widely available even as overdose deaths among people using crack, cocaine and meth rose over the last four years.

That may be starting to change. California was the first of four states to receive special clearance to use Medicaid funds for rewards, and requests from four other states are pending.

Barriers to more widespread adoption

Critics of contingency management argue patients will trade their gift cards for drugs. Many treatment providers worry the rewards could be seen as illegal payments to patients in exchange for their business. Plus, working with patients to set goals, monitor their progress and coach them through setbacks takes a lot of time and energy from staff.

Hurley and other addiction experts say the biggest challenge is limits on how much programs are allowed to give patients. Federal rules cap the total yearly value of prizes at $75 per patient per year to avoid triggering a kickback investigation. But studies suggest that rewards need to be substantial to drive behavior change.

“There’s no research to show that $75 will work,” said Richard Rawson, a professor at the University of Vermont’s Center for Behavior and Health, and the author of a paper that argues for removing some of the barriers to offering contingency management.

One recent study showed the $75 limit might do more harm than good by frustrating patients, so they don’t buy into treatment.

California has permission from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to give contingency management patients up to $599 a year.

“California’s $599 maximum is about the lowest you can go to show an effectiveness,” Rawson said.”

‘We needed to do something’

Allyson Pinkhover, the director of substance use programs at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center, considered many of the pros and cons before she applied for the grant that would let her small team offer contingency management. It was late 2020, in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic. There were disturbing reports about a spike in overdoses and deaths among people using stimulants in Brockton. Cape Verdeans like V, who didn’t realize that fentanyl could be in cocaine or crack, were particularly hard hit.

“We’d had gotten really laser focused on opioids and alcohol and perhaps were missing an entire group of people who needed treatment,” Pinkhover said. “We needed to do something.”

V was nurse Santiago’s first contingency management patient. The treatment didn’t work for V right away. He’d set a goal, then miss his weekly appointment. Or he’d come to an appointment, but his urine test would show traces of cocaine.

“But then I realized it was getting bad, like worse, and I needed help, so I started to come more often,” V said. “And she kept pushing me,” he added, with a sidelong glance at Santiago.

There are no penalties in contingency management for patients who don’t achieve a goal. They can adjust it to something manageable, or try the same goal again the next week. V set goals that reduced his use, little by little.

“I have a lot of patience,” Santiago said. “And it’s really nice to see some hope in this difficult field.”

V’s been in the contingency management program for about two years. That’s much longer than a typical program, but it took V a year to get to abstinence. He’s used contingency management to help achieve other recovery goals, too, like getting a job, going back to school and taking better care of himself.

V has a garden now, and is learning to cook using prizes he earned in the program: a rice cooker, a blender and a hot plate.

“It got me to think of ways I could do better, ways I could not use,” V said. “ ‘Cause when I’m at home, my mind is, ‘Oh, how can I get the next prize? What’s my next goal?’ ”

“It got me to think of ways I could do better, ways I could not use.”

V, patient

Dr. Wilson Compton, deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said if there are changes in the rules governing contingency management, federal agencies and addiction experts should consider a broad campaign to encourage adoption. Compton said there’s an urgent need as deaths among people using meth and cocaine remain higher than they were before the pandemic.

“While many of those deaths are due to the combination of methamphetamine or cocaine with fentanyl,” Compton said, “we’ve seen an increase in overdose deaths related to methamphetamines without an opioid like fentanyl.”

Massachusetts is spending close to $1 million a year on contingency management programs to address these overdose deaths. The state’s first clinic designed for people addicted to stimulants has treated 170 patients since opening at Boston Medical Center in 2021.

“We have patients driving in daily from more than two hours away,” said Dr. Marielle Baldwin, co-medical director at the Stimulant Treatment and Recovery Team or START clinic at BMC. “There’s a really significant need across the state and nation for more stimulant specific treatment programs.”

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Migrants show up at Logan for shelter, prompting fresh calls for state to change policies

An advocate for migrant families said he believes some families are reluctant to go into a temporary shelter, because it prevents them from getting longer-term emergency housing support.

Muslim voters say they don’t feel understood or welcomed by Republicans or Democrats

This year, some American Muslims say they feel politically homeless — not understood or welcomed by either Republicans or Democrats.

Five states planning to execute prisoners this week despite federal moratorium

Despite a federal moratorium, there have already been thirteen state executions this year. And in the next week, five people are scheduled to die.

Sudanese refugees are struggling after fleeing to Chad. Locals are being strained too

Hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees have fled to Chad, where they're facing increasingly difficult conditions as their presence strains local resources and humanitarian aid organizations.

New data sheds light — and raises objections — on COVID-19 origins

New data samples from the Wuhan market points to an intermingling of SARS-CoV-2, raccoon dogs and humans. The authors of a new paper say it bolsters the animal origin theory. Other researchers object.

The state of the presidential race in rural Georgia

Former President Donald Trump has lots of support in rural Morgan County, Ga., where immigration is a major concern.