Here’s why many election experts aren’t freaking out about certification this year

As the lead election official in one of the biggest counties in a swing state, Derek Bowens is thinking about a lot of things as voting season nears. His county just relocated its elections department into a more secure facility to protect from threats, and it unveiled an app to communicate accurate information directly to voters.

But one thing the election director of Durham County, N.C., is not worried about is election certification.

“I have not thought at all [about it],” Bowens said. “I don’t have any concerns. The law is clear.”

This is the first presidential election since Donald Trump’s sprawling nationwide effort to overturn the 2020 results, and watchdog groups and pundits have been sounding the alarm about the potential for mischief when it comes to certification. Finalizing vote tallies had typically been a mundane part of the election process, but it’s come under new focus, especially after Georgia’s state election board recently gave local boards there more latitude for investigation, even though that could violate state law.

Across the country, dozens of local officials this year are tasked with some role in certification who have shown an openness to refusing to do so, based on disproven or unsubstantiated election conspiracy theories, according to a recent report from the left-leaning Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

Despite that, election experts and the people actually in charge of tallying the votes are still projecting confidence in the certification process. That’s partly because of changes implemented since 2020 and partly because the legal system has shown an ability to be a backstop against political interference in the process.

“I’m feeling better than most people, but maybe that’s because I don’t freak out about things,” said Charles Stewart, an elections expert at MIT. “All the evidence is that state and federal courts have shut down election officials going beyond their authority and acting on hunches rather than evidence.”

Since 2020, courts have forced certification

Certification is the administrative last step of the elections process, in which local political bodies finalize the work of election officials. Trump’s efforts to sow doubt in voting processes have given way to a new trend in which local Republican officials have refused to finalize results in situations where there are no actual underlying issues.

Still, in every case since the 2020 election where a local body has declined to certify, courts have stepped in to force certification. That’s because generally, state laws don’t allow people in these positions much discretion — if any at all — not to certify, after the election has been held, challenges about voting rules have been litigated through the courts, and the local election administrator has tallied the vote.

Every state does provide some mechanism, outside of the certification process, where voters or candidates can challenge election procedures or results. And in some states, that process can only take place after local certification, so local officials holding it up may be standing in the way of legitimate investigation.

In Pennsylvania, a state that could very well swing the presidential race, Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt told NPR his office is preparing as though there will be local boards that decline to certify.

“We’re not worried but we will be prepared,” said Schmidt, a Republican who was targeted by Trump in 2020 when Schmidt was a local election commissioner in Philadelphia.

In the 2022 midterms, three different Pennsylvania counties declined to certify elections at the local level.

“And that wasn’t because the election was close, that wasn’t because there was any evidence whatsoever of voter fraud or an election irregularity,” he said.

Members of the local boards disagreed with a court ruling regarding mail ballots in the state, and Schmidt’s office eventually sued to force the counties to comply.

“It’s always possible that people can try to interfere with election administration and the timelines, which are pretty strict admittedly,” said Schmidt. “But for us, it’s a matter of working closely with the courts to make sure these matters are disposed of expeditiously.”

And since 2020, laws at the state and federal level around certification have only been made clearer, as Votebeat detailed recently.

In Bowens’ state of North Carolina, for instance, those involved in county certification are only to make sure eligible ballots have been counted, and that any mandatory recounts have been completed.

Still, after the 2022 election, two members of a board in Surry County, N.C., declined to certify due to disagreements with a court decision about election rules. The state board removed the two from their posts last year.

“Those who administer elections must follow the law as it is written, not how they want it to be,” Damon Circosta, who was chair of the state election board, said at the time.

Bowens, of Durham County, added: “Under North Carolina law, the statute says a county board of elections ‘shall’ [certify]. It doesn’t say, ‘might’ or ‘consider’ or ‘maybe.’ It says ‘shall.’ Our statutes are very clear on how the process works once we’ve completed the canvassing period.”

Questions about certification can fuel false narratives

Even if these sorts of efforts fail to actually muck up the election process in various places, UCLA election law professor Rick Hasen says they still further false election narratives, which can lead to a host of other potential problems.

“When you have government officials saying the vote counts are not fair, even if there’s no basis in doing that, it can spark conspiracy theories,” Hasen said. “It could provide the basis for people to act in a lawless way to try to overturn the results of the election.”

In fact, the first instance in 2020 where certification became a storyline was in Michigan, a state Trump lost by more than 150,000 votes.

Trump called two local Republican officials and tried to pressure them not to certify. The officials eventually did certify, but false election narratives still blossomed in the state.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election put a spotlight on all sorts of previously mundane or administrative parts of voting, like slates of electors, mail ballot drop boxes and especially the process of certification, which is the finalizing of vote totals. A new rule in Georgia could potentially open the door to a growing trend of local officials declining to certify elections. NPR voting correspondent Miles Parks joins us now. Hey, Miles.

MILES PARKS, BYLINE: Hey there.

CHANG: OK, so let’s start with certification. Tell us more about what it is and why it is such a big deal.

PARKS: Right. This is not something most people had ever thought about before 2020…

CHANG: Yeah.

PARKS: …Because it really is more of a formality, where these local political bodies, usually county canvassing boards or city commissions – they sign off and confirm the work of election officials. This was never a controversial step until the last presidential election, when then-President Donald Trump personally called two members of a canvassing board in Michigan trying to convince them not to certify the election there.

The problem is Trump and his allies seem to misunderstand the role of local certifiers. They’re not tallying votes. They’re not checking signatures or running audits. That’s the job of election officials. In every state, there are channels available to voters and to candidates if they want to challenge part of the counting process. Often this happens through the filing of lawsuits, but there are no states where this sort of certification refusal is legal.

CHANG: Right. But since that Trump phone call in 2020, we’ve heard more and more about this happening. Why is that?

PARKS: Right. So this is another sign that these sort of election conspiracy theories have seeped into every aspect of voting. In recent years, dozens of Republican local officials, often citing these conspiracy theories or some sort of patriotic duty, have voted against certification in their counties. And this is all getting new attention now because of this new rule that was passed recently by the Georgia elections board that seems to allude to these boards being investigative bodies. Many election law experts think that rule violates state law, and litigation is already pending on it.

CHANG: Well, how have the courts viewed these sorts of cases as they’ve started to pop up in recent years?

PARKS: So this is what makes election officials feel really confident this year because in every single case across the country where a county has voted not to certify, courts have stepped in forcing certification. Derek Bowens, who runs elections in Durham County, N.C., told me state law in his state has language specifically indicating people in these positions do not get discretion.

DEREK BOWENS: Under North Carolina law, the statute says a county board election shall. It doesn’t say might or consider or maybe.

PARKS: So this is not ideal. When any county declines to certify, it definitely lends credence to this idea that something is wrong, even if there isn’t evidence. But there is a general confidence in the elections community that courts will be an effective backstop against this type of interference.

CHANG: I get the sense, though, that voting officials are almost planning on this being part of their post-election process this year, right?

PARKS: Yeah, that’s definitely true at the state level. And that’s partly because many of them are now familiar with this playbook. In the midterms, for instance, three different Pennsylvania counties declined to certify because they disagreed with a court order about how to count mail ballots. Here’s Pennsylvania Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt.

AL SCHMIDT: And it wasn’t because the election was close. That wasn’t because there was any evidence whatsoever of voter fraud or an election irregularity. So we went to court and promptly compelled them to certify. So if we see that happen again in 2024, we will be ready to go.

PARKS: Schmidt told me he is not too worried about the certification issue, but his office will be prepared.

CHANG: That is NPR’s Miles Parks. Thank you so much, Miles.

PARKS: Thank you.

(SOUNDBITE OF MAHALIA SONG, “IN THE CLUB”)

2 former migrant farmworkers reflect on their journey together

Emma and Rogelio Torres reminisce about how unlikely a pairing they were when they first met as migrant farmworkers in Arizona. They met in the 80s near Yuma — with love the last thing on their minds.

Voters are advised to return their ballots early because of mail delay concerns

Election officials are raising concerns about the U.S. Postal Service's ability to handle this fall’s expected influx of election mail. But USPS say it’s ready to deliver the country’s ballots.

Deadly high blood pressure during pregnancy is on the rise

More pregnant women are being diagnosed with dangerously high blood pressure, which risks the life of the parent and child. Montana is one of the states improving screening and treatment.

Turkey wants to regulate Germany’s beloved döner kebab street food

Under Turkey's proposal, beef would be required to come from cattle that is at least 16 months old, and be marinated with specific amounts of fat, yogurt or milk, onion, salt, thyme, and pepper.

An iconic Churchill photo stolen in Canada and found in Italy is ready to return

Canadian and Italian dignitaries marked the successful recovery of a portrait of Winston Churchill known as "The Roaring Lion," stolen in Canada and recovered in Italy after a two-year search.

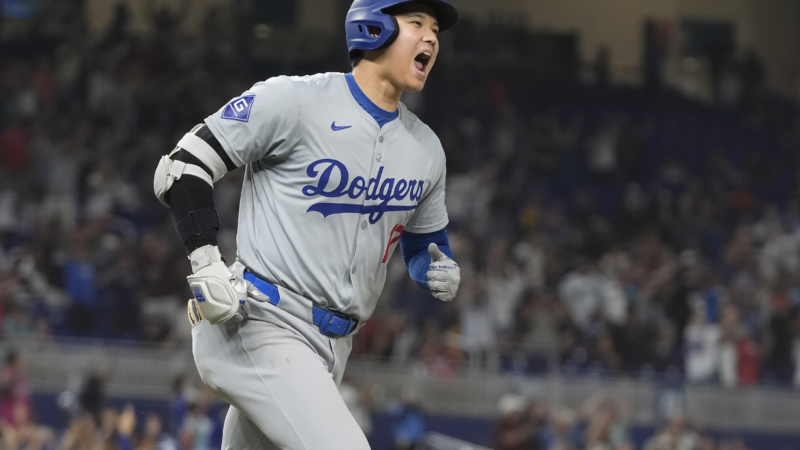

Shohei Ohtani becomes the first MLB player to top 50 homers and 50 steals in a season

The Los Angeles Dodgers star reached the 50-50 milestone in his 150th game. He was already the sixth player in MLB history and the fastest ever to reach 40 home runs and 40 stolen bases in a season.