Long before this week, South Korea had a painful history with martial law

For many people outside of South Korea, President Yoon Suk Yeol’s decision to declare martial law earlier this week was a sudden and astonishing development. But inside the country, it was a frightening reminder of past turmoil and lives lost on the path to democracy.

Yoon’s order on Tuesday was not the first time martial law has been declared in the country’s nearly 80-year history. Since its founding in 1948, South Korea has seen numerous political clashes in which martial law was decreed — including a pivotal episode in 1980 that left scores dead and a nation in shock.

The country has faced a turbulent political history that saw authoritarian rule starting from its founding after gaining independence from Japanese colonialism all the way to the 1980s, according to Charles Kim, a professor of Korean studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“This is a period in which there was a lot of political suppression, repression of the media, political violence against dissidents,” Kim said.

In all, martial law has been declared in South Korea at least 16 times, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). It has been decreed during times of war — including the Korean War — but it has also been issued by South Korean leaders who were seeking to stay in power in the face of protests, Kim said.

Martial law was first decreed in South Korea in 1948 by then-President Syngman Rhee after government forces faced a communist-led military rebellion. Rhee, who was president for 12 years, would impose it again in 1952.

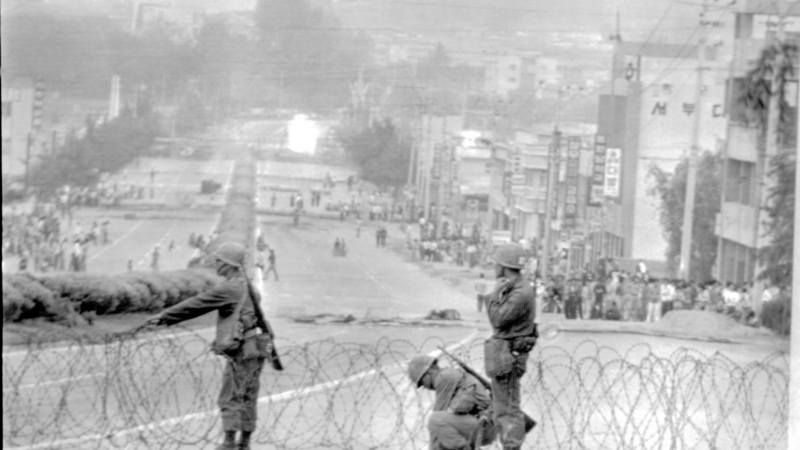

The Gwangju uprising

Before Tuesday, martial law was last declared in South Korea by Chun Doo-hwan, a general who rose to power in a coup following the 1979 assassination of President Park Chung-hee — a former general who had also declared martial law while in power to crack down on dissent.

The day after Chun declared martial law in May 1980, students in opposition to the order took to the streets, staging demonstrations against military dictatorship in the southwestern city of Gwangju. Chun responded with a violent crackdown, sending in the military to beat back the protest.

By the time it was all over, roughly 200 people had been killed, according to official estimates, but families of the survivors have said the true death toll from what became known as the Gwangju uprising is far higher.

The uprising would mark an important turning point in South Korea’s path away from authoritarian rule. While the country would not formally transition to democracy until 1987, the shock caused by the violence in Gwangju was seen as a pivotal catalyst for change that helped make Chun the nation’s last dictator.

A different time

Today, South Korea’s constitution still allows a president to declare martial law as a “response to war, incidents, or other national emergencies,” according to CSIS. However, the constitution also gives the National Assembly the ability to overturn a martial law declaration with a majority vote.

Kim from the University of Wisconsin-Madison said that Yoon made a “huge miscalculation” with his decision to declare martial law, noting that there is a difference from when it was decreed by previous leaders.

“Under these dictators in the past, they could count on the support of the parliament because they were much more aligned with the president,” he said. The president could count on the National Assembly “to not try to reverse the martial law decree in the authoritarian age.”

He added that the National Assembly’s decision to annul the decree within hours of Yoon’s declaration — along with the mass protests that broke out in response to it – sends a powerful message to Yoon and future leaders: “This is not gonna work, that this is a very different time and a painful reminder to the president that he doesn’t have the mandate of the people.”

There’s great TV coming in January, from ‘Severance’ Season 2 to a Jerry Springer doc

There is a lot of TV on deck in the new year – including multiple medical dramas, a violent Netflix drama about Utah settlers in the 1850s, plus, cop shows, Westerns and documentaries.

Life-threatening windstorm triggers wildfire in Southern California

Southern California hasn't seen significant rainfall since last April, and a pileup of dry fuel in combination with the winds has the region on edge. A mandatory evacuation order was issued for the Palisades.

Peter Yarrow of the folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary has died at 86

Yarrow wrote or co-wrote some of the group's biggest 1960s hits, including "Puff, the Magic Dragon" and "Day Is Done."

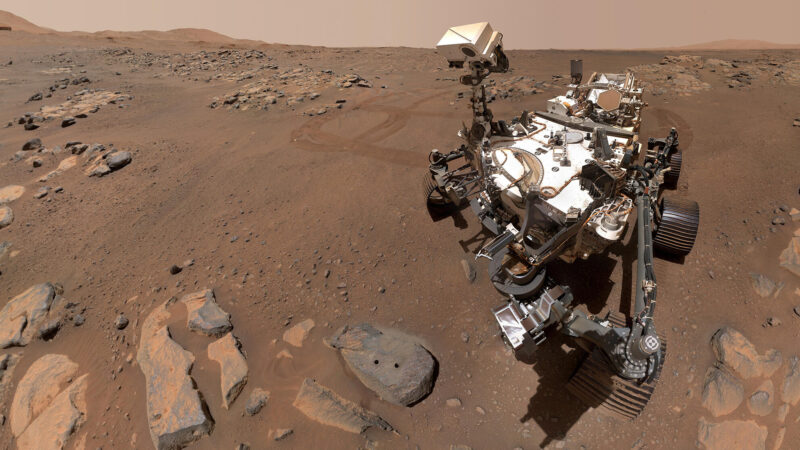

NASA hedges its bets on costly Mars rock mission

NASA has announced it is moving forward with several plans to return rock samples from Mars.

Trump in news conference says ‘all hell will break out’ if Gaza hostages not released

The president-elect made a similar pledge on social media in early December. His latest comments came during a wide-ranging news conference from Mar-a-Lago.

Meta says it will end fact checking as Silicon Valley prepares for Trump

CEO Mark Zuckerberg called the company's previous content moderation policies "censorship," repeating talking points from President-elect Donald Trump and his allies.