Kangaroo species went extinct in the Pleistocene. Research hops in with a possible explanation.

Tens of thousands of years ago, during the late Pleistocene, many large animal species were simply erased from the planet during a widespread extinction. In Australia, nearly two dozen kangaroo species vanished — but the reason hasn’t been clear.

“It’s a question that’s been plaguing paleontology for a couple of hundred years,” says Sam Arman, a paleontologist at Megafauna Central, a natural history museum in Australia

Now, in research published in Science, Arman and his colleagues say that a detailed analysis of hundreds of ancient and modern kangaroo teeth point to the arrival of humans in Australia playing a larger role in the extinction event than a changing climate.

Not everyone agrees, however. “I think looking at one spot in time is not enough to discount the role that climate may play in previous extinctions,” says Larisa DeSantis, a paleontologist at Vanderbilt University who wasn’t involved with the study.

The question of human- versus climate-induced extinction is an important one since it could help researchers disentangle the forces today that are contributing to the erasure of global biodiversity.

Kangaroo beginnings… and endings

Kangaroos evolved from a possum-like ancestor some 20 million years ago. Then, around eight million years ago, “Australia became quite arid,” says Arman.

In response, kangaroos adapted their locomotion and diets to the drier climate. “That was where kangaroos really hit their strides — or I suppose their hops — and diversified into a lot of different groups,”says Arman.

There were two major groups of kangaroos. There were the long-faced ones, “which is what you still see today, and that includes things like wallabies,” says Arman. And there were the short-faced ones. “If you plunked a koala head on top of it, you’re basically in the right ballpark, just less floofy.”

All these kangaroos lived alongside an array of other animals. “We had this marsupial that was the size of a rhino,” Arman says. “We had a marsupial lion. We had all sorts of crazy things.”

Then, about 40,000 to 65,000 years ago, most of these large animal species went extinct, including all of the short-faced kangaroos and some of the long-faced kangaroos. And the question is — why?

“It really does come down to two arguments,” says Arman.

The first is whether humans — who arrived in Australia around this time — had something to do with it, perhaps by hunting the kangaroos or altering the landscape.

The second is related to a change in climate. “If these kangaroos were all just feeding on particular sorts of plants,” says Arman, “then perhaps climate change came in and wiped out those plants and then they went extinct because of that.”

Ancient marsupial dentistry

This idea that their food disappearing leading to extinction relies on the kangaroos having been specialized eaters. Some paleontologists argue this was the case based on differences in kangaroo skull shape and chemistry — that short-faced kangaroos fed primarily on shrubs and long-faced kangaroos fed mostly on grasses.

Arman, however, wasn’t so sure. “Adaptation does not necessarily define diet,” he says. He approached the question of ancient kangaroo extinction by taking a detailed look at the teeth of more than 900 kangaroos — a mix of fossils from Victoria Fossil Cave in South Australia and modern animals from across the country.

The technique is called dental microwear texture analysis. “Whenever an animal chews its food,” Arman explains, “the food leaves marks — microscopic scratches on the surface of the teeth. If we take those teeth and scan them under a very high resolution microscope, we can then compare what these fossil animals were eating at the time.”

Arman and his colleagues found that most of the extinct kangaroos (both the short- and long-faced ones) had mixed diets. That is, he says they ate both grasses and shrubs based on what was available. The takeaway, Arman suggests, is that starvation brought on by a changing climate may not have wiped out all those kangaroos. Instead, the arrival of humans may have.

“It doesn’t rule out that climate change is involved in some other way,” says Arman, “but it’s very hard to tell the story without invoking humans in any way.”

DeSantis says that in Australia, it’s difficult to reconstruct what animals once ate in part because of the diverse landscape. “This paper is really helpful,” she says, “but I think it goes a little bit too far — that these kangaroos were already well adapted to variable climate change.”

She leans towards climate change having more to do with their extinctions. “I think you can have a tipping point,” she says. “If things get warm enough, dry enough, these animals are going to have a tough time making it, regardless of whether they’re mixed feeders.”

DeSantis says the new research doesn’t capture the full picture. “It’s really important to see if we can disentangle the impacts of climate and humans in the past,” she says, “so that we can better understand and anticipate the impacts that we’re having on current ecosystems.”

This is a point that Sam Arman agrees with. He’s hopeful that his current and future work might lead to ways to help modern-day kangaroos — particularly if the animals can adapt to eating more kinds of plants and live in more habitats than researchers once thought.

“Especially for some of our species that are becoming rarer,” he says, “we can actually consider looking at reintroductions in places where we might think that they’d be poorly adapted.”

In other words, Arman hopes the kangaroos that ended their time on Earth in the Pleistocene might help the kangaroos of today escape a similar fate.

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Tens of thousands of years ago, nearly two dozen kangaroo species vanished, part of a great extinction event. Science reporter Ari Daniel says hundreds of prehistoric teeth may now help paleontologists figure out why.

ARI DANIEL, BYLINE: Kangaroos evolved from a possum-like ancestor. Then, some 8 million years ago…

SAM ARMAN: Australia became quite arid. That was where kangaroos really hit their strides – or I suppose their hops – and diversified into a lot of different groups.

DANIEL: Sam Arman is a paleontologist at Megafauna Central, a natural history museum in Australia. He says there were two major groups of kangaroos – the long-faced ones…

ARMAN: Which is what you still see today, and that includes things like wallabies.

DANIEL: …And the short-faced ones.

ARMAN: So basically, if you plonked a koala head on top of it, you’re basically in the right ballpark – just less fluffy.

DANIEL: Then, in the late Pleistocene, 40 to 65,000 years ago, many of these kangaroos went extinct. And the question is why.

ARMAN: The question has been plaguing paleontology for a couple of hundred years. It really does come down to two arguments.

DANIEL: The first being whether humans, who arrived in Australia around this time, had something to do with it, perhaps by hunting the kangaroos or altering the landscape, or whether it was related to a change in climate.

ARMAN: If these kangaroos were all just feeding on particular sorts of plants, then perhaps climate change came in and wiped out those plants and then they were extinct because of that.

DANIEL: This idea that their food disappeared relies on the kangaroos having been specialized eaters, which some paleontologists believe, based on differences in kangaroos’ skull shape and chemistry, that short-faced kangaroos fed primarily on shrubs and long-faced kangaroos mostly on grasses. Arman, however, wasn’t so sure.

ARMAN: Adaptation does not necessarily define diet.

DANIEL: So he approached the question of ancient kangaroo extinction by taking a detailed look at the teeth of more than 900 kangaroos, a mix of fossils from a cave in South Australia and modern animals from across the country.

ARMAN: Whenever an animal chews its food, the food leaves marks – microscopic scratches on the surface of the teeth. If we scan them under a very high-resolution microscope, we can then compare what these fossil animals were eating at the time.

DANIEL: Arman and his colleagues found that most of the extinct kangaroos, both the short- and long-faced ones, had mixed diets. That is, he says, they ate both grasses and shrubs, based on what was available. He suggests that starvation brought on by a changing climate may not have wiped them out and the arrival of humans may have.

ARMAN: It doesn’t rule out that climate change is involved in some other way, but it’s very hard to tell the story without invoking humans in any way.

DANIEL: The research is published in the journal Science.

LARISA DESANTIS: This paper is really helpful in sort of reconstructing what the ecology was, but I think it goes a little bit too far in trying to make the claim that these kangaroos were sort of already well-adapted to variable climate change.

DANIEL: Larisa DeSantis is a paleontologist at Vanderbilt University. She leans towards climate change having more to do with the extinctions, so she says the new research doesn’t capture the full picture.

DESANTIS: It’s really important to see if we can disentangle the impacts of climate and humans in the past so that we can better understand the impacts that we’re having on current ecosystems.

DANIEL: This is a point that Sam Arman agrees with. He hopes the kangaroos that ended their time on Earth in the Pleistocene might help the kangaroos of today escape a similar fate. For NPR News, I’m Ari Daniel.

(SOUNDBITE OF MAC MILLER SONG, “THE MILLER FAMILY REUNION”)

L.A. is bracing for the return of more powerful winds as fires continue to burn

As firefighters continue to battle blazes in multiple fires, more Santa Ana winds in the coming days threaten to increase fire risk.

Southern California wildfires destroy or damage many houses of worship

Faith communities in Los Angeles are trying to protect their homes and houses of worship from deadly wildfires. They are also trying to provide spiritual support for their traumatized congregations.

Kate Bowler wants to have more ‘uncounted, completely-wasted, doesn’t-matter time’

On Wild Card this week, Kate Bowler opens up about how she wants to waste her time, her feelings about God and how she talks about death with her child.

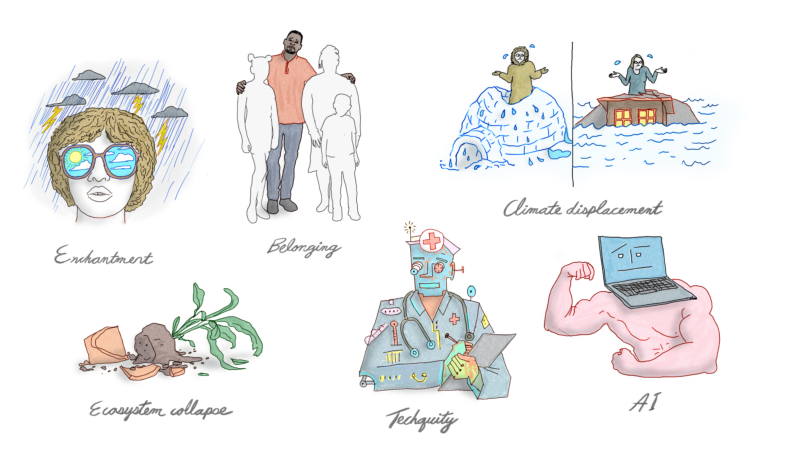

7 global buzzwords for 2025: From ‘techquity’ to ‘climate displacement’ to ‘belonging’

What words will be buzzing about in the global health and development hive in the year ahead? Our experts have nominations for your consideration.

Exit interview: DOT Sec. Buttigieg on infrastructure act and the road ahead

In an exit interview with All Things Considered, DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg reflects on the Biden administration's infrastructure act and why it didn't resonate with some voters.

How one U.S. conservationist’s work is helping to preserve Chile’s wilderness

Chile is set to gain its 47th national park early this year — largely due to the efforts of U.S. conservationist Kristine Tompkins and her organization.