K-pop’s uncertain English-language future

Years before BTS broke the seal on K-pop in America, Teddy Riley saw the vision. The R&B trailblazer, whose production and songwriting pioneered new jack swing in the 1980s and ’90s, turned an ear to Seoul in the late 2000s, producing for K-pop groups like f(x), EXO and Girls’ Generation. The marriage was arguably overdue: A generation earlier, Riley’s signature sounds had been all over the single most important breakthrough in K-pop history, the 1992 smash “Nan Arayo (I Know)” by Seo Taiji and the Boys, the first crew to not only experiment with Western influence but mimic its artistry and fashion wholesale. And so, when Riley arrived to service the now fully built pop industry that had taken shape in South Korea thanks to the “Nan Arayo” revolution, the producer was well aware of his role in the process. “They didn’t have no shame in their game. ‘We want the American culture,’ ” he told The Boombox in 2017, laying bare the source of the younger culture’s hip-hop, R&B and post-Michael Jackson disco-pop swagger. But Riley also recognized something distinctly Korean about the synthesized final product. “The only thing that inspires them is American culture and our style,” he said, “but their music is their music and it’s really territorial.”

At the close of 2024, K-pop is becoming territorial in a different sense. Earlier this month, the BLACKPINK member Rosé and the girl group TWICE, two of the genre’s towering figures, released new English-language music on the same day — the former dropping her solo debut, rosie, and the latter releasing a mini-album led by the Megan Thee Stallion-featuring title track, “Strategy.” Both have released music in English before. What’s notable this time is the seamlessness of the imitation, with many tracks feeling as though they could slide undetected into the American Top 40. The music is completely fine — and yet, there is a sedate, by-the-numbers earnestness to even the best songs, one at odds with K-pop’s usual excesses. The performance of genre is toned down to the point of feeling almost conventional. To a lover of the form, the effect is both impressive and a little unsettling. And it is representative of a movement building momentum, evident in the work of many artists capitalizing on an American breakthrough this year.

For much of its history, K-pop has been at least one step removed from the culture it predominantly echoes, owing to what the social theory scholar John Lie referred to as the “temporal gap” — the dissonance created by the physical, social and anthropological distance between cultures — in his 2015 book K-pop: Popular Music, Cultural Amnesia, and Economic Innovation in South Korea. Many of the songs and styles draw from a recognizable wellspring; some are nostalgic, others flat-out derivative. All are in conversation with a global pop diaspora that has been dominated by the U.S. (even when K-pop is engaging with Afrobeats or urbano, it is doing so because the Hot 100 says so). K-pop songs have been riddled with English hooks since the dawn of the genre, but the final product is often slightly askew — rarely fitting into traditional molds or scanning as American pop to any ear trained on Top 40 radio. For its devotees, a lot of what has worked about K-pop to this point is distinctly the byproduct of that mash-up nature, the slight discord of our sounds pushed through their system. Even for producers like Riley, who could trace the line of influence to his own doorstep, there seemed to be an understanding that meeting in the middle was not just mutually beneficial but necessary for the cultural alchemy at play.

Still, the very things that make K-pop thrilling to its fans also mark its otherness, at least from a certain business-minded perspective. The industry was built in the shadow of South Korea’s “big three” talent agencies — JYP Entertainment, SM Entertainment and YG Entertainment — which in the mid-1990s established the blueprints for a highly systematized, deeply allusive, kaleidoscopic group machinery. In tweaking that model, BTS’ label, the HYBE Corporation, has since supplanted all three, becoming its own consortium of imprints producing crossover triumphs like NewJeans, Le Sserafim, Enhyphen and Tomorrow X Together, all of which have debuted in the Top 10 of the Billboard 200. Between this transition of old and new powers, we have seen the goalposts for success move from one of sustained profitability to unfettered growth. If one’s goal is not simply commercial success, but a complete and total integration into the global pop market, then there is a strategic disadvantage in sounding merely close to what is most popular. For a South Korean music executive trying to overcome that remaining friction, it would seem the simplest path forward is to remove the most obvious differentiator — language — entirely, and strip those songs of some of their tangled eccentricities so that they blend in. There have been plenty of English songs made by K-pop groups, but most are simply the English-language versions of existing Korean singles, or afterthought deep cuts buried on releases. Only now is a persistent and widespread effort emerging to have K-pop idols create music that doesn’t just seek American ears, but prioritizes them.

It tracks that members of BTS and BLACKPINK, the first groups to really break the stateside dam for K-pop, have been among the first to aggressively target the language barrier. This year, after carefully teasing the move since 2020’s The Album, BLACKPINK members Jennie and Lisa released “Mantra” and “Rockstar,” respectively, both through American labels. “Mantra” taps into Miami bass but evokes Los Angeles; “Rockstar,” which Lisa performed at the Victoria Secret Fashion Show in Brooklyn in October, dials up hyperpop for a similarly cosmopolitan sentiment: “Every city that I go’s my city,” she sings. Since pausing their group activities in 2022, the Bangtan Boys have continued off in various directions toward the American horizon. The majority of the music they have released as soloists this year has been blatantly crossover-minded: j-hope teaming with Nile Rodgers and Benny Blanco, Jungkook trading sex bars with Latto. But the trend goes well beyond those marquee stars. The song by the girl group Kiss of Life that went semi-viral in 2024 was not their EP’s designated Korean single, but the English B-side, “Igloo.” Ditto for Le Sserrafim and its half-rapped “1-800-hot-n-fun.” The newly debuted group MEOVV launched the English single “TOXIC,” and BOYNEXTDOOR released an English cover of “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas.” NCT Dream’s “Rains in Heaven” even made it onto the Pop Airplay chart, which ranks songs being played on Top 40 radio. All of the K-pop songs to join NCT on the airwaves in 2024 — “Mantra,” Lisa’s “Moonlit Floor,” Rosé’s “APT.,” Jimin’s “Who,” and “Feeling Lucky,” a collaboration between the R&B singer BIBI and Jackson Wang, the Hong Konger of the group Got7 — are in English.

We are seeing this uptick because K-pop is more visible, accessible and approachable for Western audiences than ever before, and our ears have never been more receptive. Tik-Tok is, as much as anything else, a K-pop app: algorithmically fed, prioritizing clipped sound and shiny objects, aimed at dwindling attention spans, designed specifically for fancams and thirst-trap edits and choreographed dance challenges. If it isn’t a gateway drug to K-pop, it’s at least a pipeline. But beyond short-term gratification, this moment has been years in the making. Since 2016, K-pop has been steadily on the rise, beating long odds — most notably, a pervasive bias against foreign-language music — by circumventing traditional avenues to listenership, thanks to YouTube and streaming. Spanish-language pop has made similar inroads in America during that time, and has benefited from the internet in the same ways, but didn’t face as steep a climb. For one, there is a built-in audience for that music in the more than 40 million people who speak Spanish in the U.S. Latin pop also comes from a wide array of regions, and is produced across various creative circumstances. (The Puerto Rican star Bad Bunny, for instance, got his start on SoundCloud.) In K-pop, the small oligarchy of entertainment agencies that all but control the music and its production churn out sparkling new figurines at breakneck speed like a workshop. In a sense, you could say the model’s incessantness wore down the defenses of American cynicism. Now, we stand at a crossroads where the endgame of K-pop’s export initiative may lead away from its artistic progression.

To be fair, the idea of a globalized K-pop industry was always the goal, and cracks at a new revolution aren’t wholly novel. From the multinational girl-group project Rania in 2011 to the NCT experiment that culled 25 members from eight countries into sub-units (including NCT Dream) with the explicit purpose of niche marketing, there have been several attempts at franchising, particularly here in America, the big leagues of cultural consumerism. But we are reaching a tipping point — not just for musicians at the top of the K-pop heap back home looking to fully transition, but for executives, both inside and outside the K-pop industry, rubbing their hands together at the prospect of enhanced reach, even if it means a dilution of the cultural signifiers in action. You can see it in XG, a Japanese girl group based in South Korea that sings and raps exclusively in English. I’ve enjoyed some of XG’s songs, which feature machine-gun flows and trap drums. But not only is the group playing into the facsimile of rap culture now treated broadly as internet culture, it does not seem to be speaking to or for anyone in particular. K-pop isn’t exactly built for individuality, but this is music so all-encompassing as to become flat. The mission statement for the group’s label, XGALX, sounds like start-up jargon: “Through XGALX’s unique creativity in music and content, we aim to break down the walls of common sense and fixed ideas, create new values through creativity, and communicate to young people around the world.”

Take, as another example, KATSEYE, a new girl group formed on the 2023 reality show Dream Academy in collaboration between the HYBE Corporation and Geffen Records. The sextet was launched with a lofty objective: a “global girl group” that would “transcend national, cultural, and artistic boundaries.” It has since become evident that “global” actually just meant “Western,” and that the group’s backers weren’t looking to transcend cultural boundaries so much as create something cultureless. KATSEYE sings entirely in English. Its music is produced by ASCAP mainstays like Ryan Tedder and Cashmere Cat. Only one of its six members is Korean. (K-pop trainee programs are known for plucking would-be members from across the Korean diaspora — Rosé, for one, is a child of Korean immigrants raised in Australia — but those moves have often served the performance of K-pop’s soft power, rather than feeling like plausible deniability through tokenism.) Though the group is clearly cosplaying K-pop, in practice, it is anything but. In an interview with Korea JoongAng Daily, HYBE founder and chairman Bang Si-hyuk admitted as much before betraying his true intentions: “It’s time to use the K-pop production system overseas to find new talents across the globe,” he said, generating a product “targeted to the American market.” K-pop, he seemed to say, was not a genre but a workflow.

K-pop agencies build their groups through a rigorous process that begins with a trainee program, auditioning teenage boys and girls to fit a particular group aesthetic. The “idols,” as they’re called, sign contracts that allow the label to control every aspect of their career and public life. Members are arranged by function (e.g., a main rapper or dancer), and each new release brings a new concept, whose highly choreographed routines are performed on various Korean music shows for months before the cycle repeats. The revelation that the same formula might be applicable in the American market — the auditions for KATSEYE drew 120,000 applicants — has found some U.S. stakeholders eager to aid the assimilation. “It has been great to be able to teach them about our market and how they can perform better in it,” Allison Kaye of HYBE America told told Billboard. “I think it’s the first true East-West partnership as it relates to talent.” In March, HYBE struck a 10-year deal with UMG, linking the biggest games in their respective towns, and by August the label had doubled down on its “multi-home, multi-genre” plan to bring “the K-pop methodology to the American pop scene,” under the stewardship of polarizing talent manager Scooter Braun. So far, that methodology has been a chart gold mine. Last month, three K-pop albums were in the Top 10 of the Billboard 200 for the first time ever — this after Rosé recently became the first female K-pop act to reach the Top 10 on the Hot 100. Last week, rosie debuted at No. 3 on the Billboard 200, the highest ever for a Korean woman.

The timing of this export operation feels a touch ironic. For one thing, as concern about A.I. slop intensifies, it’s bizarre to imagine intentionally treating K-pop — as rare a phenomenon as we’ve seen in music this century — as merely an outlet for generically engineered musical copypasta. But this expanding approach to the music’s business model also comes at a moment where the apparatus itself is under scrutiny. Recent scandals have resurrected longstanding concerns about the ethics of commodifying idol worship: In April, NewJeans, perhaps the most critically revered K-pop act of all time, found itself at the center of a labor controversy that led one of its members to provide tearful testimony for a broader investigation into workplace culture in the South Korean entertainment industry. In July, Brian Kim, founder of Kakao Corp. (who won a controlling stake in SM Entertainment after a battle with HYBE), was arrested for allegedly manipulating the stock price during his attempted acquisition. In November, NewJeans announced the termination of its contract with HYBE on the grounds that the company had breached the agreement. The industry at large rallied against the move: “If we allow such a method of contract termination to take place, who could ever invest in the Korean K-pop market?” the Korean Entertainment Producers Association said in a statement.

NewJeans is the K-pop ideal: referential but aesthetically focused, systematic but not mechanically so, broadly appealing but unmistakably Korean, marked by good taste and personal style. Considering that, it’s jarring to learn that even the best case scenario is subject to the whims and evils of industry. It’s worth noting that many K-pop groups don’t make it to year three: Promo cycles are brutal and exhausting, and idols’ lives are carefully stage-managed in ways that can’t help but breed strife. Labor practices in the American record business aren’t known as wholesome either, but in the NewJeans equation it seems that the star-aligned serendipity of the group’s music, in which the configuration of artist, producers, songwriters and choreographers feels perfectly and harmoniously matched, only barely balances the weight of an oppressive operational infrastructure. If HYBE’s endgame is a K-pop for America, and for the world, there is a real threat of sacrificing the best parts for the worst parts: Franchise the efficiency, lose the identity.

What is the sound of K-pop, if one exists beyond language? And if it has a singular sound, why would this push disrupt that? While K-pop does borrow far too broadly to have any one unified sonic theory — after all, its acts go through conceptual evolutions every few months, pegged to various music trends — I’d argue that the sound’s inherent kitsch owes to its need to negotiate so many layers of context, and that it is in that negotiation that one can see and hear personality beyond the system. At its best and most charming, K-pop music is about liminal space — the journey between cultural poles, favoring neither the origin nor the destination but the tension of landing in the middle. Processing all that is lost in translation creates songs that are decidedly not American pop, existing in awe of and in opposition to it all at once. Stripping the music of those conditions can leave it sterile and boring, even when “better.”

There are a lot of reasons why the model works — beautiful young people drawing the parasocial desires of even younger fans; its perfectly packaged, hypnotizing use of synchronization; its climate-controlled atmosphere — and why it may again elsewhere. But I’ve always liked the idea that something so blatantly commercial could produce something almost paradoxically custom-made: as cosmically twee as WJSN’s “Secret,” as reverential as Heize’s “And July” or as bonkers as Girls’ Generation’s “I Got a Boy.” How else can one explain the “Gangnam Style” phenomenon — in which a firecracker of a song from a character who looks like anything but an idol, written about a very Korean experience, became the biggest YouTube hit ever at the time — than with a volatile cultural chemistry whose imprecision is its greatest asset?

It must be said that the “old K-pop” is far from dead. The boy band ATEEZ, who were at the front of the pack the week of K-pop’s big Billboard takeover, embodies all of the chaotic maximalism of the genre, and there are plenty more where they came from. You can find the NewJeans ideal in sister group Illit, or in ARTMS’ Dall, the best and most intoxicating K-pop full-length of 2024. But HYBE’s 10-year UMG deal feels like a harbinger: The shift is coming, and the threshold is closer than ever. I don’t want to be all doom and gloom. I do see the vision. Honestly, one could think of Rosé’s chart-storming Bruno Mars collab “APT.” as a logical next step in K-pop’s evolution: Instead of pairing Korean verses with an English hook, it does the opposite, and instead of reaching for a sound that is strikingly contemporary to the point of setting one’s teeth on edge, or so nostalgic for a bygone era as to feel alien, it is intentionally just a bit passé. Including Mars, the world’s greatest karaoke star, is a clever touch. Rosé performed the song on Fallon and at the MAMA Awards, which is kind of like the K-pop Grammys. But it’s telling that the MAMA ceremony was held in the U.S. for the first time in its history this year. On the brink of yet another K-pop revolution, the next battleground is here.

9 movie scenes I couldn’t stop thinking about in 2024

From a heart-wrenching epiphany in the drama Tuesday to a meme-able moment in Challengers, these were the lines that critic Aisha Harris has remembered all year.

‘We are not California’: New Jersey dealers push back on electric truck rules

Vehicle dealers are pushing back on rules that would increase the number of electric trucks sold in New Jersey. It could be a preview of a brewing fight over state rules about cars.

For young adults, caregiving isn’t just hard. It can shape you for life

Caregiving responsibilities can cut young people off from peers and interrupt their emerging life story. And there's been little research or support directed at this group. That's starting to change.

The fun — and confusion — of celebrating Christmas and Hanukkah on the same date

Christmas and Hanukkah rarely fall on the same date, but this year they do. One mixed-faith family in Oakland, Calif., doubles down for double whammy holiday.

What the Israel-Hezbollah war did to Lebanon’s cultural heritage sites

Part of a Crusader castle crumbled. An 18th century minaret felled. Church mosaics burned. Archaeologists are assessing damage to UNESCO World Heritage Sites from Israeli strikes on Lebanon and Syria.

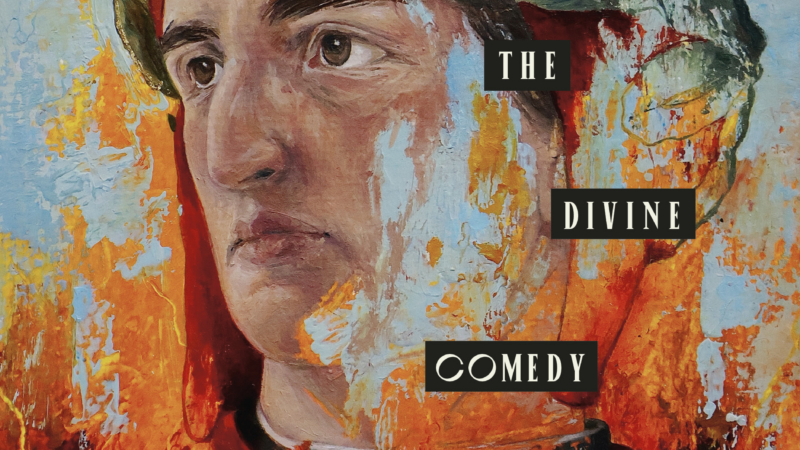

There’s a new translation of Dante’s ‘The Divine Comedy.’ Why?

Dante Alighieri is one of the pillars of Western literature. And his texts have been translated into English dozens of times. With two new translations of his work out now, it's worth asking – why do we keep returning to this well?