It’s a virus you may not have heard of. Here’s why scientists are worried about it

A little-known virus is getting a lot of attention this year. It’s called Oropouche, and it’s been making headlines because of a notable increase in diagnoses.

So far in 2024 there have been over 10,000 cases, mainly in South America and the Caribbean. The vast majority are in Brazil. By contrast, the total Oropouche count in Brazil recorded between 2015 and 2022 was 261.

In August, PAHO, the Pan American Health Organization, issued an epidemiological alert urging for increased prevention, surveillance and diagnosis of the viral infection, which is spread by the bite of a mosquito or a midge (a kind of fly that bites humans).

Now there’s a new concern. A study published in the CDC’s journal, Emerging Infectious Disease in October reports that sexual contact might be a way to transmit the virus.

“This is a very big development,” says Dr. Tulio de Oliveira, director for the Center of Epidemic Response and Innovation at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, who was not involved in the study.

The midge connection

The virus was first identified in 1955 and named for the village in Trinidad where it was found. The pronounciation: “o-ro-push.”

Oropouche is harbored in birds, monkeys, rodents and sloths.

It’s an arbovirus like dengue, Zika and Chikungunya –—the term refers to any disease caused by insect bites. If a mosquito or a midge — a tiny fly – bites an infected critter and then goes for a blood meal from a human, the virus can take root.

The fact that midges spread it is a serious issue. “Biting midges are known as ‘no-see-ums,’ ” says Dr. Chris Braden, deputy director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. “They’re so small they can actually fly through standard window screens.” They’ve long been considered a nuisance, leaving itchy welts or spurring allergic reactions with their bites. But this understanding that they can transmit a virus that harms humans raises biting midges to a new level of concern. They’re an emerging disease vector that hasn’t been well-studied.

And what happens if you get a bite and catch the virus? Symptoms of Oropouche infection are typical of many viruses and usually last a week: fever, rash, muscle aches, headache. But some cases can be more severe, causing encephalitis and meningitis —inflammation of the brain and its surrounding membrane that can cause it to swell. And as with Zika, a mother can transmit the virus to the fetus during pregnancy — which can lead to birth defects and even fetal death.

“There have been a few cases of maternal to fetal transmission, and there are four cases of congenital Oropouche infections that have been described — all of which led to microcephaly, which is a small head size,” said Dr. Davidson Hamer, infectious disease doctor and professor of Global Health and Medicine at Boston University School of Public Health. “What is really scary is that [there has been a] miscarriage and most recently a stillbirth,” he added.

“This woman [who had a stillbirth] was in her mid-pregnancy and developed a fever and symptoms typical of dengue but also typical of Oropouche and then a couple days later her baby stopped moving. So she went and got an ultrasound done and it showed her baby had died,” described the infectious disease doctor. “They took biopsies from multiple tissues and everywhere

they samples [they found] Oropouche virus.”

Sexual transmission

And now there’s the new evidence suggesting that Oropouche could spread in yet another way: through sex.

On August 2, 2024, a man who had been in Cuba from July 19 to 29 was diagnosed with Oropouche in a hospital in Italy. He had developed a fever his last day in Cuba. During his recovery, researchers used PCR tests to look for the virus in his blood, urine and semen. To their surprise, they not only found the virus in his semen 16 days after his symptoms started — and 6 days after they had completely resolved — but they also found that the virus was still able to replicate and spread.

“This can open a new route of transmission,” said Dr. Tulio de Oliveira of Stellenbosch University.

The study was conducted in the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital in Verona, Italy. The results were concerning enough that the findings were published as an early release article in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal. According to the CDC, early release publications are reserved for studies “with urgent public health importance.”

“This [possibility of sexual transmission] brought up more questions than answers,” said Dr. Hamer, whose collaborators were involved in the study.

But Dr. Hamer emphasized that we have no documented cases of sexual transmission yet. What we know now is that sexual transmission could happen — not that it has.

Nonetheless, this potential for sexual transmission was serious enough for the CDC to issue a provisional guidance on November 4th, recommending that male travelers who develop Oropouche symptoms after visiting areas with Level 1 or 2 Travel Health notices for Oropouche to “consider using condoms or not having sex for at least 6 weeks” from the start of their symptoms.

“Because stillbirths, birth defects, and severe complications and deaths in adults have been reported, CDC is providing interim recommendations on preventing possible sexual transmission based on what we know now,” reads the statement in the CDC website.

The role of deforestation

This new potential route of transmission doesn’t explain what Dr. Hamer described as “an explosion of cases.”

“The number of cases is something like 60 times higher than in previous years,” he says.

The virus was initially confined to the Amazon Basin. Even in the epicenter of Brazil, fewer than 100 cases of Oropouche per year were reported between 2015 and 2022. “So, there’s been some change — something’s happened,” said the infectious disease doctor.

Dr. de Oliveira thinks deforestation may be partly to blame. When trees are felled and people move in, typically to farm, they come into close contact with the mammals that live in the Amazon forests — and the mosquitoes and midges that bite all of them.

“So now the virus that was circulating between midges and mammals [is near] people,” he says. “And then these people acquire

the virus, and what do they do? They [travel back and forth] to the big cities.”

That can result in the spread of the virus to more people. And if anyone who’s infected travels travel to a different country, then the virus can spread there as well.

A newer, stronger strain

Deforestation isn’t the only factor helping Oropouche thrive. Dr. Hamer said that we now have evidence that the virus itself may have changed through a process called viral reassortment.

He explains that reassortment is one way that segmented viruses — like Oropouche – create new strains. As the name implies, segmented viruses are made up of multiple smaller segments — or units. You can think of these as detachable pieces of the virus. If two segmented viruses infect the same cell, they can mix and match their segments to create a new, hybrid version. This hybrid version is what you would call a new strain of the virus.

A study by Brazilian infectious disease researchers published on The Lancet in October found that the Oropouche virus has changed so much that people who had immunity to it in the past no longer do. “Basically, it suggested that the virus has undergone a reassortment and it is very different from what had been circulating previously,” explains Dr.

Hamer. “People who had immunity from past episodes — 5, 10 years ago — they could become infected again.”

And not only can this version of the virus infect people who had been immune before, it may infect people faster than ever before — explaining the current unprecedented spread. “It looks like it grows much more rapidly – it might be a more virulent strain of

the virus,” says Dr. Hamer.

Looking ahead

Neither expert thinks we are on the brink of a global outbreak quite yet. “We are alerted about [Oropouche] but not concerned that it will cause a global outbreak yet,” says Dr. de Oliveira who led the team that first detected the omicron variant of COVID-19 in South Africa.

“The challenge is that this is such a new disease that most clinicians — including infectious disease specialists — are not aware of it and we need to make more patients and health-care providers aware of the disease and increase access to diagnostics so we can test for it,” says Dr. Hamer. “Over the next year, we are going to learn a lot more.”

NPR correspondent Pien Huang contributed to this story.

Party City files for bankruptcy and plans to shutter nationwide

Party City was once unmatched in its vast selection of affordable celebration goods. But over the years, competition stacked up at Walmart, Target, Spirit Halloween, and especially Amazon.

Sudan’s biggest refugee camp was already struck with famine. Now it’s being shelled

The siege, blamed on the Rapid Support Forces, has sparked a new humanitarian catastrophe and marks an alarming turning point in the Darfur region, already overrun by violence.

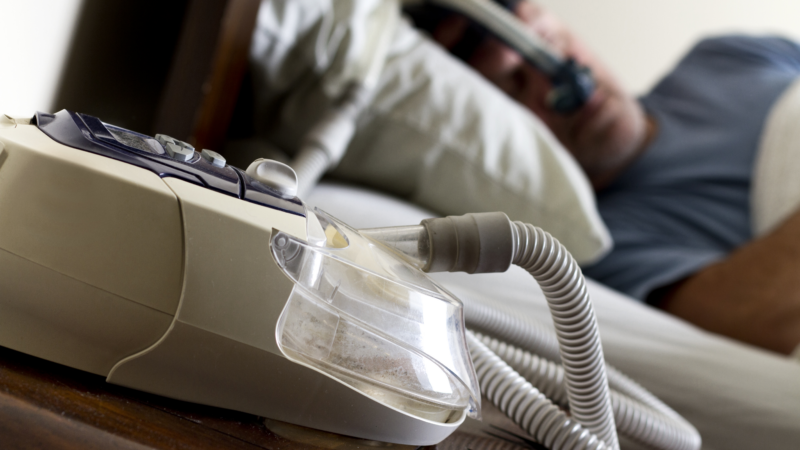

FDA approves weight loss drug Zepbound to treat obstructive sleep apnea

The FDA said studies have shown that by aiding weight loss, Zepbound improves sleep apnea symptoms in some patients.

Netflix is dreaming of a glitch-free Christmas with 2 major NFL games set

It comes weeks after Netflix's attempt to broadcast live boxing between Jake Paul and Mike Tyson was rife with technical glitches.

Opinion: The Pope wants priests to lighten up

A reflection on the comedy stylings of Pope Francis, who is telling priests to lighten up and not be so dour.

The FDA restricts a psychoactive mushroom used in some edibles

The Food and Drug Administration has told food manufacturers the psychoactive mushroom Amanita muscaria isn't authorized for food, including edibles, because it doesn't meet safety standards.