In ‘A Real Pain,’ Jewish cousins tour Poland, cracking jokes and confronting the past

We live in an era of ceaseless, shocking normalization. Things that were once thought beyond the pale — today’s political discourse, say, or TV ads for ED — are now accepted as routine. These days, it no longer seems bizarre that there’s an industry devoted to taking tourists to Holocaust sites — with fancy food and hotels as part of the package.

One person who clearly finds this kind of tourism odd is Jesse Eisenberg. Indeed, such a tour forms the spine of A Real Pain, a quietly thrilling movie that he wrote, directed and co-stars in. Following two cousins on a Jewish heritage tour of Poland, Eisenberg uses this cockeyed version of a road movie to tell a funny, moving, casually profound story about family, friendship, the weight of the Jewish past, the weight of everyone’s past and the different ways one deals with suffering.

Eisenberg plays David Kaplan, a prosperous, married ad salesman who is taking this Polish tour with his cousin Benji — that’s Kieran Culkin — a wounded soul with whom he was once quite close. They plan to end their trip by visiting the hometown of their recently deceased grandmother who escaped one of the camps. But first, under the eyes of a well-meaning gentile British guide — an excellent Will Sharpe — they join a small group that includes a melancholy divorcee played by Jennifer Grey, and a Tutsi survivor of the Rwandan genocide — that’s Kurt Egyiawan — who has converted to Judaism.

As the group visits graveyards and memorials, heading toward the Majdanek death camp, David and Benji josh around, kvetch, reminisce about the past, smoke weed on Warsaw rooftops and try to figure out a relationship that’s changed over the years. Where Eisenberg’s David is stressed and responsible, Culkin’s Benji has a sort of Lenny-Bruce style manic depression — he can get everyone laughing with his sunny, profane directness, then thunderclap into emotional darkness. David envies Benji for his truth-telling panache. Benji envies David for having a wife and son to love him.

A Real Pain is an almost perfect little film, whose tiny flaws make it more human

A Real Pain is an almost perfect little film, whose tiny flaws make it more human — it’s never preeningly artful. But artful it is, sharply written and directed with a delicate feel for ambivalence and ambiguity; there’s no cheap emotion in it. The scene when Benji and David reach their grandmother’s house is a gem of shifting emotional and historical overtones.

And the stars are just terrific, playing nifty riffs on two familiar types. Eisenberg shines as an anxious good guy who, caught up in work and his own head, has trouble seeing and emotionally engaging with those who are unhappy, partly because they make him feel guilty. Although David may actually learn more on their trip than his cousin, Benji is the flashier part and Eisenberg generously gives it to his co-star.

As his Roman Roy in Succession made clear, Culkin knows how to make us enjoy, and have sympathy for, the pinball-machine flamboyance of damaged men. His Benji may be mired in emotional distress, yet he still sees the sadness behind other people’s eyes and refuses to pretend it’s not there. Even as he leads the group to pose comically on the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto — David keeps an uneasily respectful distance — Benji’s also the tour member who explodes when they travel first class on a Polish train, given the meaning of trains in Jewish history. “People can’t go around being happy all the time,” he snaps.

Although it’s filled with great jokes, A Real Pain tackles something big and hard. It explores how we confront pain, an inescapable reality that ranges from the epic horror of industrial murder that guts David and Benji at the death camp, to personal losses that are no less real because they aren’t as historically vast as the Holocaust.

With the lightest of touches, Eisenberg’s stunning film got me thinking about the different ways we deal with suffering, both past and present. Should we simply “get on with life,” as David seems to, or should we take that pain into ourselves, as does Benji? Or is there a way to somehow do both?

The U.S. economy is growing solidly. Here’s what’s working — and what’s not

The U.S. economy grew at an annual rate of 2.8% in the third quarter, led by strong consumer spending. The news comes days before a presidential election in which the economy has been top of mind for many voters.

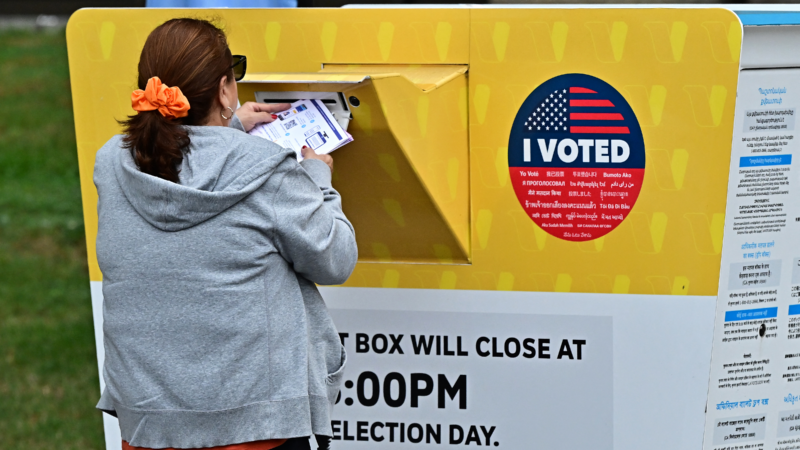

Worried about your 2024 ballot being counted? These states let you track it online

“There's no need to panic,” an elections expert tells NPR. All but three states have free tracking sites that send updates to voters as their ballot goes through the system.

Handsy fans disrupted a World Series game. Here are 5 notable MLB interference cases

Two Yankees fans were ejected from Game 4 of the World Series for trying to pry a ball out of a Dodgers player’s glove. It's a particularly brazen instance of fan interference, but far from the first.

Shortage of IV fluids leads to canceled surgeries

IV fluids used in hospitals remain in short supply, after Hurricane Helene shut down a key North Carolina factory. The closure has hospitals scrambling to stretch supplies and prioritize care.

Spain flooding: Photos show the devastation in Valencia

Authorities in the region report at least 70 people have been killed after torrential rain overpowered the area.

Supreme Court allows Virginia to purge individuals from voter rolls

The court's order comes less than a week before the 2024 general election.