Impossible, you say? Try asking a toddler

Even toddlers can tell an event that is improbable from one that appears impossible. And children at that age are much more likely to remember an occurrence that is unimaginable to them, a team reports in the journal PNAS.

“Those kids are really motivated to learn,” says Lisa Feigenson, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and a co-author of the study.

Feigenson and Aimee Stahl of The College of New Jersey did an experiment that involved 335 2- and 3-year-olds.

“We wanted to know how little kids think about possibilities,” Feigenson says.

Their first challenge was getting the attention of kids that young, so the scientists designed a special gumball machine filled with toys.

“It turns out that the opportunity to put a little coin in a machine and get a prize is very naturally motivating to kids,” Feigenson says.

When a toddler got a toy from the machine, the scientists told them it had a made-up name: blick. Later, they were asked to point to the blick in a lineup of toys.

When the toddlers knew the transparent machine contained blicks, they were unsurprised by their prize and usually forgot its name. This was true even when the machine had only one or two blicks amid lots of other toys.

But the toddlers responded very differently when they got a blick from a machine that appeared to have none, a seemingly impossible event.

Often, “kids’ eyes get wide, and their jaws drop, and they look at their mom in surprise that this has happened,” Feigenson says.

Moreover, when toddlers encountered this completely unexpected result, they usually remembered the blick’s name.

“There was this really big learning boost for kids who had seen the ‘impossible’ event,” Feigenson says.

The results add to the evidence that even very young children learn better when they encounter the unexpected, says Andrew Shtulman, a professor at Occidental College who was not involved in the study.

“It elicits a level of surprise that leads to more attention, better encoding of the events, and better retention of those events later on,” he says.

But kids are less able to distinguish improbable from impossible events when there’s no physical evidence, like an unexpected blick, Shtulman says.

For example, after hearing a story that mentions eating pickle-flavored ice cream, four-year-olds will maintain that this could not happen in real life, Shtulman says.

“Anything that violates their expectations, they deny is possible,” he says, unless they see evidence to the contrary.

Overall, this sort of research contains a powerful message about how young children respond to the unexpected, Shtulman says.

“If you want children to learn something deeply and for a long time,” he says, ”you violate their expectations prior to introducing that information.”

Research suggests that once children understand how an “impossible” event occurred, they tend to lose interest.

States and cities beef up security to prepare for potential election-related violence

Washington state's governor activated the National Guard to stand by to help local law enforcement as needed. Meanwhile, extra security is in place at locations across Washington, D.C.

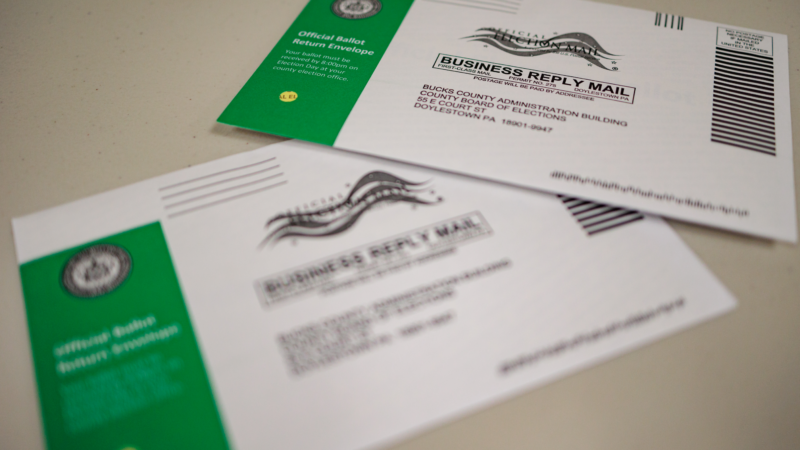

When will mail-in and absentee ballots be counted?

Various state rules regarding when election officials can process and count mail ballots means it will likely take some time after Election Day before the results from these ballots are fully known.

When do polls close in every state? Here’s a timeline

The Associated Press can't call any races until polls close in their respective state. Here's a breakdown of when that will happen.

How has the Electoral College survived, despite being perennially unpopular?

Despite its substantial-sounding name, the Electoral College isn’t a permanent body: It’s more of a process. For decades, a majority of Americans have wanted it to be changed.

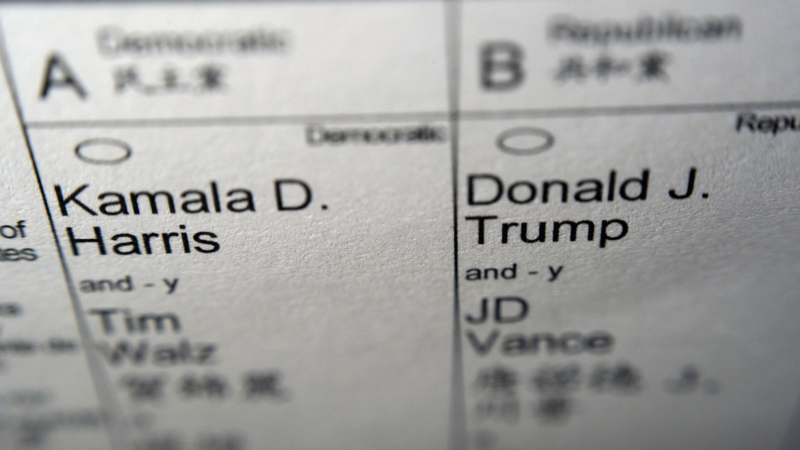

Thousands of Pennsylvania voters have had their mail ballot applications challenged

Thousands of last-minute challenges to voters’ mail ballot applications, along with baseless claims by former President Donald Trump, are adding pressure on Pennsylvania county officials.

No more fluoride in the water? RFK Jr. wants that and Trump says it ‘sounds OK’

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s claims about fluoride in the drinking water are linked to Cold War conspiracy theories about the substance.