How the gutting of USAID is reverberating around the world: Worry, despair, praise

Schools. Vaccination programs. Medication and medical equipment. Media organizations. Literacy programs.

All face the chopping block after the Trump administration moved to gut the United States Agency for International Development, the government’s foreign aid organization. Over the weekend, a federal judge put a temporary hold on Trump’s plans to lay off 2,200 employees. President Trump has accused the agency of widespread waste and members of his administration have criticized the funding of programs that do not align with U.S. foreign policy goals. After his inauguration, he put virtually all of the agency’s programs on a 90-day pause to be evaluated. Within days, USAID was shut down as an independent agency.

The agency, set up by then-President John F. Kennedy in 1961 at the height of the Cold War, currently provides humanitarian and development assistance in over 100 countries.

Its supporters say it helps save lives, strengthen civil society, assist the needy and promote and preserve democracy, while presenting a gentler version of the U.S. — as a global superpower willing to aid and help some of the world’s most vulnerable. A $42 billion soft-power glove, in their eyes, to go along with the Pentagon’s nearly $900 billion hard-power fist.

USAID has faced accusations of inefficiency and waste over the years, including that it fails to measure the effectiveness of its programs. Much of USAID’s money is handed out as grants or is subcontracted to aid groups and NGOs. Critics contend that USAID’s use of American contractors, and its large bureaucracy means that not enough of the money actually ends up helping those in need. It’s also been criticized for what some countries have alleged is a backdoor for the U.S. to interfere in their domestic affairs.

Many within USAID have acknowledged the need for reforms and were willing to work with the administration. But a senior USAID official, who spoke to NPR last week on condition of anonymity because they are not authorized to speak on behalf of the agency, decried the Trump administration’s methods as a “hatchet job.”

Here’s a look at some of the work USAID has done around the world — and the effect the cancellation of its work is having on local communities.

Ukraine: A fear of loss, from health care to media

KYIV, Ukraine — Since Russia’s full-scale invasion on Feb. 24, 2022, Ukraine has been the largest recipient of USAID funds. It’s received $37 billion over the last three years — aid that has touched practically every aspect of Ukrainian life.

The money paid the salaries of emergency service workers; supplied farmers with fertilizer, seeds and storage capacity; and has been used to rebuild Ukraine’s power grid after repeated Russian missile strikes.

Oleksandr Merezhko, a member of parliament from President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s party, says the money has provided a lifeline to Ukraine.

“There are lots of programs that are very useful, including support of our war veterans, programs related to health care, support of parliament,” said Merezhko.

The chaos at USAID is already having an impact on the ground. Olena Horyacheva, who runs a medical charity Vykhid in the southern city of Mykolaiv, says programs providing treatment for tuberculosis and HIV have already shut. Screening programs for these diseases are also subsidized by USAID funds.

“We paid to deliver antiretroviral therapy [drugs] to HIV patients who could not get to a hospital or see an infectious diseases specialist,” said Horyacheva. “We worked with medical institutions so nurses could send out those parcels every month.”

The cuts have also hit regional Ukrainian media hard. One media advocacy group estimates that “9 out of 10 outlets rely on subsidies and USAID is the primary donor.”

The news website Cykr in the northeastern city of Sumy is one of them, and its editor said 60% of its budget came from USAID.

“So now we have a big challenge,” said Dmytro Tyschenko, Cykr’s editor. “We’re trying to communicate with our European partners to cover [the shortfall].”

Tyschenko adds that the news site only has the money to keep the lights on for another month. The alternative, he warns, is unfiltered social media where Russian propaganda flourishes.

Merezhko, the lawmaker, says he hopes the Trump administration will revive USAID after reviewing or overhauling it.

“It’s important not only for Ukraine, it’s important for the United States,” said Merezhko. “Let’s not forget about the information war on the part of Russia and China.” —Joanna Kakissis

South Africa: Concern about HIV drugs

JOHANNESBURG — South Africa has the highest number of people living with HIV in the world — over 8 million by some estimates — but with USAID support for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, the country has made significant inroads with prevention and treatment in recent years.

The effects of USAID cuts are already being felt on the ground — and among the most vulnerable.

At the Engage Men’s Health clinic in Johannesburg there’s a notice on the door: “Regrettably our clinic is temporarily closed.”

Alex, 30, who only used his first name because of the stigma associated with HIV, told NPR he’s been coming to this clinic for years to collect his pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. the medication that prevents HIV infections, and is often prescribed to high-risk individuals. (The drug is also taken by people who are HIV positive, reducing their risk of developing AIDS as well as the chance they can transmit the virus.)

“We had a safe space. This place also caters for LGBT. So, a lot of people, they can be in the closet and they don’t want their family to find out, they’d come to this clinic,” said Alex.

While the South African government provides the antiretroviral drugs, about 17% of its other HIV funding comes from PEPFAR, amounting to about $440 million a year. The government estimates 15,000 health-care workers could lose their jobs.

“Although the South African government pays for most of the country’s antiretroviral medication, so it doesn’t receive any help from the U.S. government to pay for the medication, it does receive significant help from non-profit organizations who are funded by the U.S. government to staff public sector clinics with health workers,” said Mia Malan, editor of the health journalism site Bekisisa.

“It doesn’t help to have all those pills if you can’t get them to the people who need them. And for that you need health-care workers,” she added.

Professor Salim Abdool Karim, an award-winning epidemiologist, said in South Africa, the biggest blow would be to prevention services.

“Where we will see an impact, where PEPFAR has a disproportionate role to play, is in areas of prevention,” says Karim.

While South Africa is one of the richest countries on the continent and is looking at contingency plan to fill the gap, poorer nations like Mozambique and Malawi depend almost entirely on PEPFAR — and losing it could be catastrophic for them, according to Abdool Karim.

“The entire AIDS pandemic will be under threat in that we could now see a resurgence of AIDS infections because patients are stopping their medications,” says Karim. —Kate Bartlett

Latin America: A welcome for Trump’s stand, with reservations

MEXICO CITY — Some Latin American countries — long-suspicious of U.S. motives in the region — have, on the other hand, welcomed Trump’s moves on USAID.

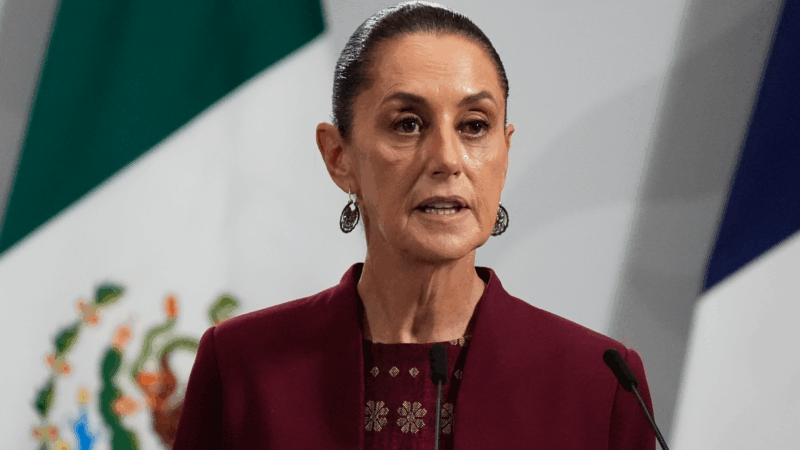

Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum said that if the U.S. actually wants to help countries, it should be transparent.

“But USAID has so many parts that the truth is it’s better that they close it down,” said Sheinbaum in one of her daily briefings.

El Salvador’s president Nayib Bukele rejoiced at the news. He wrote on X that the majority of USAID funds are “funneled into opposition groups, NGOs with political agendas.”

Both the Salvadorean and Mexican governments have complained bitterly that U.S.-funded journalism and human rights outfits that have uncovered corruption and human rights abuses are meddling in their internal affairs.

In Colombia, President Gustavo Petro said the U.S. shouldn’t be funding public employees in his country. Hundreds of immigration officers, he said, were paid with U.S. funds.

“Trump is right,” Petro said. “Take your money.”

None of this is surprising to those who watch the region closely.

“Not one bit, no,” says Jake Johnston, director of International Research at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “These sort of democracy- promotion things, which are political interventionism in sovereign countries, it is a part of what USAID does.”

In both Mexico and El Salvador, for example, USAID-funded investigative journalism outfits have uncovered vast corruption or human rights abuses by the incumbent governments. Both countries have also bitterly complained that USAID funds the opposition.

Another reason for the region’s skepticism, said Johnson, is that USAID rarely awards money directly to governments.

“USAID money goes almost entirely to contractors, NGOs or multilateral agencies like the U.N.,” says Johnston, the author of Aid State, a book critical of USAID’s role in Haiti.

USAID funds private clinics or schools or more, to the point, they fund private corporations in the United States that run clinics or schools in Haiti. That means USAID programs — often with serious overheads — run in parallel to public institutions.

Even food aid, which saves lives, has been controversial. In Haiti, for example, as USAID pumped free rice into the country, local producers of rice could not compete with free so they went out of business. Today, Haiti imports nearly all of its rice and buys it from U.S. companies.

Johnston says USAID has created toxic dependencies and does need an overhaul — but what Trump is simply trying to destroy it.

Johnston says stopping or changing some USAID programs may be necessary, but it would be harmful to do it from one day to another, because many people around the world have come to depend on those programs for survival.

“You’re just gonna cause a bunch of people to lose their jobs and a bunch of people to lose life- saving support,” says Johnston. — Eyder Peralta

South and central Asia: A loss for secret schools, female journalists

MUMBAI, India — USAID has done a lot of heavy lifting across South Asia.

In Afghanistan — where there’s an ongoing humanitarian crisis — the aid agency’s education projects have been suspended, including what are known as “secret schools.”

These schools are meant to educate hundreds of Afghan girls after the Taliban banned them from all learning beyond sixth grade.

USAID-funded work to support Afghan women includes a project to train female journalists, in partnership with the news outlet Zan Times.

“We need to fully understand what is happening to [Afghan women],them,” says the editor Zahra Nader, under a Taliban regime that she describes as creating “gender apartheid in Afghanistan.”

The outlet’s mission is to tell the stories of Afghan women — which needs Afghan women journalists, says Nader. The outlet says its mission is to try and tell the stories of Afghan women.

“How are we going to cover this? How can we tell their stories when we don’t have access to them?” she asked. Nader says the notification of the suspension of funds “came on the day that we were supposed to start our first online class.”

“We couldn’t dare tell this group of women journalists who are joining us online from Afghanistan,” said Nader, in an interview from the U.S.

In Bangladesh, a developing country of 170 million people, where a student-led uprising recently toppled the country’s longtime leader, USAID funded everything from vaccines to food security. USAID has long funded local versions of Sesame Street across the globe, from the Palestinian territories to Afghanistan, as a way of teaching tolerance, literacy and empathy to children, particularly those who have experienced war and displacement.Republicans and conservative media outlets have pointed to a recent $20 million grant to create an Iraqi version of Sesame Street as proof of waste at USAID.

USAID funds also helped pay for programs to screen for and treat tuberculosis. A doctor, who worked on the project to teach medics how to screen for the disease, told NPR that USAID money helped train around 3,000 pediatricians. Tuberculosis is highly contagious and it’s often children who aren’t diagnosed. The doctor spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing his group will be denied future funding from Washington.

He also said that USAID purchased and delivered arranged for 28 ultra-portable X-ray machines for far-flung hospitals to screen for the disease, and that 10 more X-ray machines were on the way.

The suspension of aid, he said “is going to have severe consequences. Many more people are going to die.” — Diaa Hadid

Ahmade Hussain contributed reporting from Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Polina Lytvynova from Kyiv.

Transcript:

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

When President John F. Kennedy set up the United States Agency for International Development or USAID, it was the height of the Cold War. Kennedy envisioned the agency as a critical humanitarian tool and a way of countering the Soviet Union around the world.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

JOHN F KENNEDY: The people who are opposed to aid should realize that this is a very powerful source of strength for us. It permits us to exert influence for the maintenance of freedom.

RASCOE: One of the people now opposed is President Trump. Over the years, USAID has faced accusations of inefficiency and waste. It has also helped fund and support humanitarian work in more than 100 countries on behalf of the U.S., the world’s largest donor of humanitarian aid. Now that the Trump administration has begun to dismantle the agency and freeze foreign aid, we’ll turn to Diaa Hadid in Mumbai, Kate Bartlett in Johannesburg, Eyder Peralta in Mexico City and first up, Joanna Kakissis in Kyiv.

JOANNA KAKISSIS, BYLINE: Ukraine is the largest recipient of USAID funds. It’s received $37 billion in the last three years since Russia’s full-scale invasion. That aid has touched practically every aspect of Ukrainian life, says Oleksandr Merezhko, a member of parliament from President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s party.

OLEKSANDR MEREZHKO: There are lots of programs which are very useful, including support of our war veterans, programs related to health care, support of parliament.

KAKISSIS: And paying the salaries of emergency service workers. It’s also kept farmers in business, and it’s helped rebuild Ukraine’s power grid after repeated Russian strikes. Now that the Trump administration is dismantling the agency, the chaos has left many in limbo, including Olena Tolkachova (ph), who runs a medical charity in the southern city of Mykolaiv. She says programs providing treatment for tuberculosis and HIV have shut down for now.

OLENA TOLKACHOVA: (Through interpreter) We paid to deliver antiretroviral therapy to HIV patients who could not get to a hospital or see an infectious diseases specialist. We worked with medical institutions so nurses could send out those parcels every month.

(SOUNDBITE OF TYPING)

KAKISSIS: The cuts have also hit local Ukrainian media. The news website Cukr in the northeastern city of Sumy relies on USAID funding.

DMYTRO TISHCHENKO: More than 60% of our budget.

KAKISSIS: Dmytro Tishchenko is Cukr’s editor.

TISHCHENKO: So now we have a big challenge. We’re trying to communicate with our European partners to cover that.

KAKISSIS: He says Cukr has enough money for just another month. And Sumy, a front-line city frequently attacked by Russia, depends on facts, he says, not unfiltered social media compromised by Russian propaganda. Merezhko, the lawmaker, says he hopes the Trump administration will revive USAID after reviewing or overhauling it.

MEREZHKO: It’s important not only for Ukraine. I think it’s important for the United States, and besides, let’s not forget about information war on the part of Russia and China.

KAKISSIS: He says without USAID, the United States will leave a void that will quickly be filled by Russia and China.

I’m Joanna Kakissis in Kyiv.

DIAA HADID, BYLINE: USAID used to do a lot of heavy lifting in South Asia, as well as in Afghanistan, where there’s been an ongoing humanitarian crisis. Now, amid chaos in Washington, the aid agency’s education projects are suspended in Afghanistan. That includes secret schools for hundreds of Afghan girls after the Taliban banned them from learning beyond Grade 6. USAID funded other work to support Afghan women, including a project to train female journalists. That was through a news outlet called Zan Times. The editor, Zahra Nader, tells NPR this project is now on hold.

ZAHRA NADER: The notification actually came on the day that we were supposed to start our first online class, and we couldn’t dare to tell to these women journalists who were joining us online from Afghanistan.

HADID: Nader says it feels like Afghan women are being abandoned. In Bangladesh – a fairly poor country of about 170 million people – USAID had all sorts of projects, including a popular local version of Sesame Street. USAID last year shared a video of one of the Bangladeshi puppets, Halum, the tiger.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, “SISIMPUR”)

ASHRAFUL ASHISH: (As Halum, non-English language spoken).

HADID: USAID also took on quite big public health issues in Bangladesh, like a project to screen and treat tuberculosis patients. And NPR producer Ahmede Hussain spoke to a doctor who worked on that project. He requested anonymity. He wasn’t allowed to speak to the media, fearing his group will be denied future funding from Washington. He told NPR that Bangladesh likely has about 3.7 million people infected with tuberculosis or TB. It’s a highly contagious bacterial infection that can be deadly.

But many Bangladeshis don’t know they’re infected, so USAID funded a program to teach medics to screen for the illness that included training around 3,000 pediatricians because it’s often children who aren’t diagnosed. USAID was also funding TB centers to treat patients. And the doctor NPR spoke to says more people will be infected as a result, and he says more lives are going to be lost.

I’m Diaa Hadid in Mumbai.

KATE BARTLETT, BYLINE: South Africa has the highest number of people living with HIV in the world, over 8 million by some estimates. In recent years, it’s made great inroads with prevention and treatment, and much of that is down to the support of USAID with its funding of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief or PEPFAR.

I’m standing on the street in Johannesburg outside the Engage Men’s Health clinic. It’s sponsored by PEPFAR and there’s a notice saying, regrettably, our clinic is temporarily closed because the funder has pulled their services.

ALEX: So I just came today just to do collection of my PrEP medication.

BARTLETT: I bump into 30-year-old Alex (ph) on the street outside the clinic. He’s been coming here for years to collect his pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP. We’re not sharing his second name for medical privacy reasons. PrEP medication prevents HIV infections in people at high risk.

ALEX: This place is also catered for LGBT. So a lot of people, they can be in, you know, in the closet, and they don’t want their family to find out. They would come to this clinic.

BARTLETT: HIV-positive people in South Africa are bracing themselves for tough times ahead. While the government here provides the antiretroviral drugs, about 17% of its other HIV funding comes from PEPFAR. That’s about $440 million a year. The government here says 15,000 health care workers stand to lose their jobs.

SALIM ABDOOL KARIM: The way we will see an impact is in areas of prevention.

BARTLETT: Professor Salim Abdool Karim, an award-winning epidemiologist, has spent his career fighting HIV in South Africa. He says people can still receive ARVs at government hospitals. While South Africa is one of the richest countries on the continent, places like Mozambique and Malawi depend almost entirely on PEPFAR.

KARIM: The entire aids pandemic will be under threat, and that we could now see a resurgence of AIDS infections because patients are stopping their medication.

BARTLETT: He also says HIV research will be hit hard. Several large programs he was involved in have already come to an abrupt halt. Back outside the shuttered clinic, Alex is trying to work out how to get his medicine.

ALEX: I am devastated that the infection is going to skyrocket. Yeah, it has actually affected us in a great way.

BARTLETT: We’re now living in fear, he says.

For NPR News, I’m Kate Bartlett in Johannesburg.

EYDER PERALTA, BYLINE: In Mexico, President Claudia Sheinbaum did not mourn the loss of USAID money.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT CLAUDIA SHEINBAUM: (Speaking Spanish).

PERALTA: “If the U.S.,” she said, “actually wanted to help develop countries, it should be transparent.”

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

SHEINBAUM: (Speaking Spanish).

PERALTA: “But USAID has so many parts, that the truth is, it’s better that they close it down.” On the platform X, the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, rejoiced at the news, saying the majority of USAID funds are, quote, “funneled into opposition groups, NGOs with political agendas.” In Colombia, President Gustavo Petro said the U.S. shouldn’t be funding public employees in his country.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT GUSTAVO PETRO: (Speaking Spanish).

PERALTA: “Trump is right,” Petro said, “take your money.” I asked Jake Johnston at the Center for Economic and Policy Research if this surprised him.

JAKE JOHNSTON: Not one bit. No.

PERALTA: Johnston wrote “Aid State,” a book critical of USAID’s role in Haiti, and he says, this reaction across Latin America comes because of two main reasons.

JOHNSTON: These “democracy promotion,” quote-unquote, things, which are political interventionism in sovereign countries, is a part of what USAID does.

PERALTA: In both Mexico and El Salvador, for example, USAID has funded investigative journalism outfits that uncovered vast corruption or human rights abuses by the sitting governments. Both countries have bitterly complained that USAID is funding the opposition. The second reason is more complicated – USAID rarely awards money directly to governments.

JOHNSTON: The USA funding goes almost entirely to contractors, NGOs or multilateral agencies like the U.N.

PERALTA: It means that USAID programs with serious overheads run in parallel to public institutions like hospitals and schools.

JOHNSTON: And that often, runs in direct contradiction to or undermines those public systems.

PERALTA: In Haiti, for example, as USAID pumped free rice into the country, local production couldn’t compete and went bankrupt. It means today, Haitians import rice from U.S. companies, and this, says Johnston…

JOHNSTON: It forces people off of their land into either the city to search for low-wage employment or to leave the country altogether and migrate to the United States or elsewhere.

PERALTA: Johnston says USAID has created toxic dependencies and does need an overhaul. But…

JOHNSTON: But that’s not what’s happening here. And instead, you’re just going to cause a bunch of people to lose their jobs and a bunch of people to lose life-saving support.

PERALTA: In Haiti, for example, the end of USAID could mean the end of HIV medicine or even lifesaving food.

Eyder Peralta, NPR News, Mexico City.

RASCOE: And we also heard from Kate Bartlett in Johannesburg, Diaa Hadid in Mumbai and Joanna Kakissis in Kyiv.

Italian fashion designer Valentino dies at 93

Garavani built one of the most recognizable luxury brands in the world. His clients included royalty, Hollywood stars, and first ladies.

Sheinbaum reassures Mexico after US military movements spark concern

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum quelled concerns on Monday about two recent movements of the U.S. military in the vicinity of Mexico that have the country on edge since the attack on Venezuela.

Trump says he’s pursuing Greenland after perceived Nobel Peace Prize snub

"Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize… I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace," Trump wrote in a message to the Norwegian Prime Minister.

Trump has rolled out many of the Project 2025 policies he once claimed ignorance about

Some of the 2025 policies that have been implemented include cracking down on immigration and dismantling the Department of Education.

Can exercise and anti-inflammatories fend off aging? A study aims to find out

New research is underway to test whether a combination of high-intensity interval training and generic medicines can slow down aging and fend off age-related diseases. Here's how it might work.

U.S. lawmakers wrap reassurance tour in Denmark as tensions around Greenland grow

A bipartisan congressional delegation traveled to Denmark to try to deescalate rising tensions. Just as they were finishing, President Trump announced new tariffs on the country until it agrees to his plan of acquiring Greenland.