How one Ukrainian chef is fighting for culinary independence

KYIV, Ukraine — Ukraine’s most famous chef, Yevhen Klopotenko, calls himself a “culinary independence fighter.” His longtime weapon is borsch, the meaty beet stew that’s synonymous with Ukrainian identity. And he even wielded it last month on Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

“Your life will be divided into two: Before you tried my borsch and after you tried my borsch,” Klopotenko told Blinken, who dined at the 37-year-old chef’s Kyiv restaurant, 100 rokiv tomu vpered (100 years back to the future), during an official visit. (Often written “borscht” in English, the stew is also widely eaten across Eastern Europe and Russia.)

Klopotenko is best known for leading the successful campaign to list borsch on UNESCO’s list of cultural heritage in urgent need of safeguarding. This was part of his longtime quest to, as he calls it, “de-colonize” Ukraine’s cuisine, which he says has been stifled for centuries by Soviet communism and Russian imperialism. Klopotenko has worked for years with historians to pore through Ukrainian literary manuscripts for references about dishes cooked hundreds of years ago.

His English-language cookbook, released earlier this year, The Authentic Ukrainian Kitchen: Recipes from a Native Chef, was forged as Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine raged.

“If you speak about the war, day after day, it’s not giving you good emotions,” Klopotenko says. “But when you cook, you have good emotions. It’s like a continuation of the story about Ukraine.”

Recipes include borsch (of course), including a vegetarian version with a plum butter called levkar, as well small fluffy cheesecakes (syrnyky) from Lviv, garlicky pork roast and buns (pyrizhky) stuffed with a variety of fillings (cabbage and meat). He points out that the recipes are designed for a home cook to make easily.

“That’s the idea of this book: to give opportunity [to] all people who speak English to touch our cuisine and to put our culture inside of yourself,” he says. “I want to share our culture.”

NPR first met Klopotenko just before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. He was wearing a Christmas sweater, holding a beet and nervously joking that he had stockpiled two years’ worth of buckwheat to help survive a new invasion by “our crazy neighbor.” Days later, as Russian troops marched toward Kyiv, his restaurant, known for its gourmet take on traditional Ukrainian cuisine, became a bomb shelter. Sheltering with his family just outside the capital, Klopotenko cooked like each meal would be their last.

“If you saw the film Don’t Look Up, and they were sitting and eating together in the last scene,” he told NPR just after the invasion, referring to the moments in the film before a comet killed everyone on Earth. “I felt something the same.”

In early 2022, as thousands of Ukrainians fled cities bombed by Russian troops and headed to western Ukraine, Klopotenko drew inspiration from Spanish chef José Andrés and his charity organization World Central Kitchen and opened a pop-up restaurant in the city of Lviv.

“I was standing in the Lviv railway station, I was cooking borsch and I saw the people … crying because [they were] running from the bombing,” he says. “And I felt like there was no more future, only one day, today. And it’s still the same. [The war] is part of life.”

Now, speaking at his bustling restaurant, Klopotenko is noticeably more subdued than he was before the war. Yet with his green-painted nails, mohawked curls (an adapted Cossack hairstyle) and joyous laugh, he still vibrates with energy. He waves at a crew setting up at the restaurant to tape a scene for Master Chef Ukraine, a competition he won in 2015. He talks excitedly about plans to open more restaurants, even outside Ukraine, and relishes telling a story about how his borsch became an ice cream flavor as part of a charity fundraiser for military drones.

“You eat meat ice cream,” he says. “It’s ice cream without the sugar, just frozen borsch. Even for me it was like …. whoa.”

Klopotenko also cooks on his YouTube channel, where he shows his nearly half-million subscribers how to make not only borsch and other Ukrainian staples but also a good lasagna bolognese. In addition, he travels around Ukraine looking for undiscovered local recipes and wants to peruse the 400-year-old diaries of monks to try to find lost Ukrainian dishes.

The Soviet Union “killed all our documents about food,” he says, “so we don’t know what Ukrainian food was like in the 16th century or 17th century. I will dig for it. It’s important.”

Klopotenko senses that the world, immersed in new conflicts and atrocities, is losing interest in Ukraine’s plight. He’s seen it happen with other long wars, like the one that subsumed Syria. He followed news of that war closely and remembers cooking Syrian recipes, “trying in my way to connect with the culture, to support it.” Then the world began tuning out, as if Syria “had just disappeared.”

“I don’t want Ukraine to disappear in such a way,” he says. “That’s my biggest motivation in doing what I do.”

NPR’s Polina Lytvynova contributed to this report from Kyiv.

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

We met the famed Ukrainian chef Yevhen Klopotenko just before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. He wanted the world to know that the hearty beet stew called borscht is not Russian.

YEVHEN KLOPOTENKO: (SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

KLOPOTENKO: You said Ukrainian borscht face? Ukrainian borscht face.

SIMON: Now with the war well into its third year, the chef still cooks and has a new English language cookbook. NPR’s Joanna Kakissis spoke to him in Kyiv.

JOANNA KAKISSIS, BYLINE: No one leaves Kyiv without trying even Yevhen Klopotenko’s smoky, sweet borscht, even if you have just a day in town, like Antony Blinken did last month.

KLOPOTENKO: Hello. Nice to meet you. It’s a pleasure for you to be here.

KAKISSIS: The chef told the secretary of state, look, after today, your life will be divided into two parts.

KLOPOTENKO: Before you tried my borscht and after you tried my borscht.

ANTONY BLINKEN: That’s what I’ve heard.

KLOPOTENKO: You’ve heard that. I think that your dream will come true today.

I will cook borscht once in a month, but then I will change the planet (imitating shooting).

KAKISSIS: Klopotenko is 37, with green-painted nails and what looks like a curly-haired mohawk. We speak at his folksy restaurant where Blinken dined and where we first met the chef before the war.

KLOPOTENKO: Yeah, I remember. I remember sitting there.

KAKISSIS: Yeah. That’s right. We were sitting over there. That’s right. And a whole lot has happened since then.

KLOPOTENKO: Yeah, yeah.

KAKISSIS: Klopotenko’s restaurant became a bomb shelter in the early days of the invasion. As Ukrainians fled west, he opened up a pop-up diner in the western city of Lviv.

KLOPOTENKO: I was standing in the Lviv railway station, I was cooking the borscht, and I saw the people who I was giving them the food and they were, like, crying because they said that I had no food for the three days because I was running from the bombing. And it’s still the same. Let’s start to be the part of life.

KAKISSIS: Also part of life during this long war, he says, is staying sane. He does it by cooking.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

KLOPOTENKO: (Speaking Ukrainian).

KAKISSIS: And showing Ukrainians how to cook. His YouTube channel has almost half a million subscribers.

KLOPOTENKO: If you speak about the war for day after day, it start to be hard, you know, because it’s not gives you good emotions But when you cook, you have good emotions. So it’s like a continuation of the story about Ukraine.

KAKISSIS: His new cookbook, “The Authentic Ukrainian Kitchen,” breaks down those recipes in English. They include a vegetarian version of borscht with plum butter, as well as stuffed buns and small fluffy cheesecakes.

KLOPOTENKO: That’s the idea of this book, to give opportunity of all people who speaks English to touch our cuisine and to put our culture inside of yourself. So I want to share our culture.

KAKISSIS: What his cookbook does not include is borscht ice cream. A local ice cream company did turn Klopotenko’s borscht into a novelty flavor to raise money for military drones.

KLOPOTENKO: If you will eat the vanilla, OK, it’s very nice. You will eat with the pistachio, nice, or with the strawberry, mmm, chocolate, mmm, borscht, ugh.

KAKISSIS: (Laughter).

KLOPOTENKO: Dun, dun, the end (ph).

KAKISSIS: There’s only so much you can do with borscht, right?

KLOPOTENKO: Yeah, yeah. I mean, like you eat, for example, meat – meat ice cream. It’s ice cream without the sugar. It’s just the borscht – borscht, frozen borscht. Even for me it was – you know? Whew.

KAKISSIS: Borscht is now on Unesco’s cultural heritage list, largely because of Klopotenko. He says it’s part of a wider push to decolonize Ukrainian culture.

KLOPOTENKO: So before the USSR and before the Russian Empire, we were the part of the world, yeah? And then we started to be the part of the Russian Empire or the USSR. We were afraid to lose our identity, like who we are.

KAKISSIS: And that fight for identity, he says, has become more important as this war drags on. He brings up another long war, the one in Syria, which he followed closely. He cooked Syrian recipes in solidarity. And then he says, the world stop paying attention to Syria.

KLOPOTENKO: And so this country just disappears.

KAKISSIS: …Disappears.

KLOPOTENKO: Yeah, and that’s what I felt. And then – yeah, yeah, I don’t want Ukraine to disappear in such a way.

KAKISSIS: He’s digging through 400-year-old diaries of monks to find lost Ukrainian dishes, he’s criss-crossing Ukraine to find undiscovered local recipes, and of course, he’s making borscht.

Joanna Kakissis, NPR News, Kyiv.

Snowboarder’s death in Swiss Alps avalanche is a reminder that even pros face risk

The death of an Olympic snowboarding athlete is a reminder that even the most skilled and experienced athletes are not immune to the threat of avalanches, and that knowledge is key to staying safe.

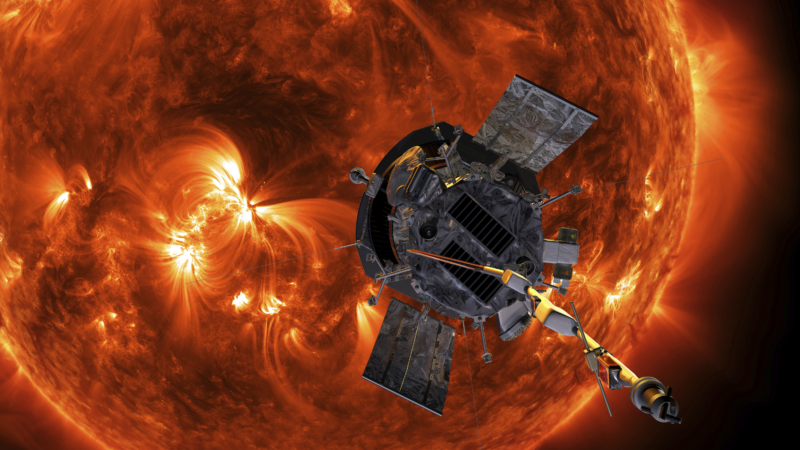

Scientists await signal from spacecraft after historic close encounter with the sun

To get so close, the Parker Solar Probe had to withstand the sun's extreme heat and radiation like no spacecraft before it.

Mega Millions jackpot surges past $1 billion

The Mega Millions prize has now grown to an estimated $1.15 billion, which could be the fifth-largest jackpot in the game's history.

Pope urges ‘all people of all nations’ to silence arms in Christmas address

Pope Francis in his traditional Christmas message urged "all people of all nations" to find courage "to silence the sounds of arms and overcome divisions" plaguing the world, from the Middle East to Ukraine, Africa to Asia.

A gang attack on a Haitian hospital reopening kills 2 reporters and a police officer

Street gangs forced the General Hospital in Port-au-Prince to close earlier this year. As journalists gathered to cover its reopening, suspected gang members opened fire.

Far from the front lines, Ukrainians fight a war to preserve their culture

In the Transcarpathia region, some locals embrace a traditional lifestyle and cultural identity. After surviving Soviet threats, now they fear President Vladimir Putin seeks to erase their culture.