Hazardous chemicals in food packaging can also be found in people

Thousands of chemicals used in food packaging and food production are leaching into food itself.

“It’s [from] your soda can, your plastic cooking utensils, your nonstick frying pan, the cardboard box that your fries come in,” says Jane Muncke, a toxicologist based in Zurich. “It’s retail food packaging, but also the processing equipment, and your [kitchenware] and tableware at home.”

More than 3,600 chemicals found in food packaging are also found in human bodies, according to a paper published Tuesday in the Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. The research was led by Muncke and her colleagues at the Food Packaging Forum Foundation, a nonprofit research group focused on hazardous chemicals in food packaging.

The paper synthesizes data from other published sources that document the presence of certain chemicals in humans from samples of blood, urine and breast milk. Of the 3,600 chemicals found in both food packaging and in humans, the researchers say about 80 are known to have “hazard properties of high concern” to human health.

Heat and time accelerate leaching

Many of the chemicals in food packaging are ingredients in plastics and can be found in clothing, furniture and personal care products. But Muncke says food packaging is a particular concern, because it can contaminate what people eat.

Food packaging can chemically react with food. You may have observed this if you’ve ever stored tomato sauce in a plastic tub and seen a reddish residue in the container that doesn’t wash off. “That’s because the molecules, which give the sauce its red color, have diffused into the plastic,” Muncke says. “That happens the other way around also — chemicals from your plastic can diffuse into food.”

The chemical leaching can be hastened by heat, time, whether a food is acidic or fatty, or how much food is touching the container.

High concern for some chemicals

Many of the 3,600 chemicals haven’t been well-studied for health effects.

But some have known links with health problems. The study identified about 80 chemicals on the list that are of “high concern” — linked to conditions like certain cancers, developmental disorders, heart and metabolic diseases.

“Chemicals like phthalates, bisphenols, metals — I think there’s pretty robust evidence to suggest that there are adverse health effects,” says Dr. Robert Sargis, an endocrinologist at the University of Illinois who was not involved with this study, though he’s worked with Muncke on others.

Phthalates, for instance, are known to be endocrine disruptors and can interfere with the body’s hormones. They’re used to make plastics flexible and durable, such as in the clear wrap on cucumbers at the grocery store.

The chemicals can be hard for shoppers to spot and avoid. “The fact of the matter is, we don’t know where this stuff is, and we don’t know 100% how we’re getting exposed to it,” Sargis says.

Chemicals can start clearing the body in days

The effects of these chemicals can accumulate over time, contributing to chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes and heart disease, says Dr. Leonardo Trasande, a pediatrician and director of the Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards at NYU Langone Health. Trasande wasn’t involved with this study, though he has collaborated in the specialized field of health and plastics research with Muncke and Sargis.

In a study published earlier this year, Trasande and his collaborators estimate that health problems related to exposure to harmful chemicals in plastics cost the U.S. $250 billion a year. The analysis included both direct medical costs and indirect costs, such as lost productivity due to disability. “We didn’t [look into] food packaging as a subset of that, but I’m going to say that’s probably a big driver,” Trasande says.

It is possible to reverse some health effects by reducing chemical consumption, Trasande says. He says some of these chemicals, such as BPAand phthalates, can start clearing the body within days after stopping exposure. “If you sustain those interventions, you change hormone levels in weeks, and you change your disease profile in months,” he says.

Trasande recommends against microwaving or dishwashing plastic food containers. He says stainless steel and glass are less likely to react chemically with food.

Researchers say regulators could do more to help by requiring better labeling for chemicals in food packaging. That could help consumers make better choices. Restrictions on chemicals with known harms in food production and packaging would also help. “We need to get out of the rabbit hole of focusing on plastic bags as a way to reduce plastic exposure,” Trasande says. “We need to think about food packaging.”

The Foodservice Packaging Institute and the Plastic Industry Association didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In testimony submitted for a congressional hearing on Sept. 10, Jim Jones, deputy commissioner for human foods at the Food and Drug Administration, stated: “The food industry is responsible for ensuring the safety of the chemicals they use in foods, including food packaging and other food contact materials, and FDA’s ability to assess the safety of these ingredients in the food supply is both reliant on and limited by the availability of this safety data.” Still, he recognized, “Congress, state legislatures, and stakeholders have made clear that chemical safety is a priority we need to address.”

The FDA will hold a public meeting on Sept. 25 to discuss how to improve the agency’s supervision of chemicals in food, including in food packaging.

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

Some other news – a study just found more than 3,000 chemicals in food packaging is in human bodies.

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

Wait, I eat Cheetos. Are you tell me the bag is bad for me, too?

INSKEEP: (Laughter) Yes. NPR’s Pien Huang reports.

PIEN HUANG, BYLINE: Chemicals from food packaging and food making are leaching into food.

JANE MUNCKE: It’s your plastic cooking utensil. It’s your nonstick frying pan. It’s your – I want to say chips, but in the U.S., you say fries (laughter) – the paper that your fries come in, or the cardboard.

HUANG: Jane Muncke is a toxicologist, and managing director of the Food Packaging Forum in Switzerland. It’s a nonprofit research group that focuses on hazardous chemicals in food packaging. She co-authored a study, out this week, in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology.

MUNCKE: So we pulled together all of these data where people had measured food packaging chemicals in blood or in human urine, and so on and so forth, and there’s an overlap of 3,601 chemicals.

HUANG: Three thousand six hundred and one chemicals that are found in both food packaging and in humans. Muncke says one of the ways people get exposed is when the food and the packaging have a chemical reaction. You’ve probably seen it if you’ve ever stored tomato sauce in a plastic container.

MUNCKE: The container’s red, right? That’s because the molecules, like, give the sauce its red color. They have diffused into the plastic. And that happens the other way around, also, so chemicals from your plastic can diffuse into your foodstuff.

HUANG: She says that chemical leaching is hastened by heat, time, whether a food is fatty or acidic and how much of the food is touching the container. Now, this doesn’t mean that all 3,000 of these chemicals are definitely bad for you. Many haven’t been well-studied for health effects, but some are associated with health problems. Dr. Robert Sargis is an endocrinologist at the University of Illinois.

ROBERT SARGIS: Chemicals like phthalates, bisphenols, metals – I think there’s pretty robust evidence to suggest that there are adverse health effects.

HUANG: The study identified around 80 chemicals of high concern, related to health problems like cancers, developmental disorders and heart disease. But Sargis says these specific chemicals are hard to avoid.

SARGIS: The fact of the matter is we don’t know where this stuff is, and we don’t know 100% how we’re getting exposed to it.

HUANG: Like which containers and materials and uses are better or worse. In any case, these chemical effects accumulate over time. Leonardo Trasande is a pediatrician and researcher at New York University’s medical school. And he says studies show that some of these chemicals, like BPAs and phthalates, start clearing your body pretty quickly after you stop ingesting them.

LEONARDO TRASANDE: And if you sustain those interventions, you change hormone levels in weeks. You change your disease profile in months.

HUANG: Researchers say regulators could do more to help. They call for better labeling to help consumers choose, more research to understand the health effects, and restrictions on using the chemicals with known harms in food production and packaging. In the meantime, for individuals, they recommend not microwaving or dishwashing plastic food containers, and using more materials like stainless steel and glass, which are less likely to react chemically with food. Pien Huang, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Whooping cough cases spike in the U.S., after people missed vaccinations during pandemic

Infectious diseases experts say many Americans fell behind on their whooping cough vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic, which they say has compounded the recent uptick in cases.

U.K. dads are wrapping baby slings on male statues to push for more paternity leave

The purpose is to raise awareness on the U.K.'s low paternity leave benefits, which currently stand at two weeks of paid time off for new fathers.

The contest in one New Mexico swing district mirrors a larger, anxious electorate

Democrats and Republicans both think they can win the state's Second Congressional District — one of the swingiest in the country — where immigration and abortion rights are dominating the debate.

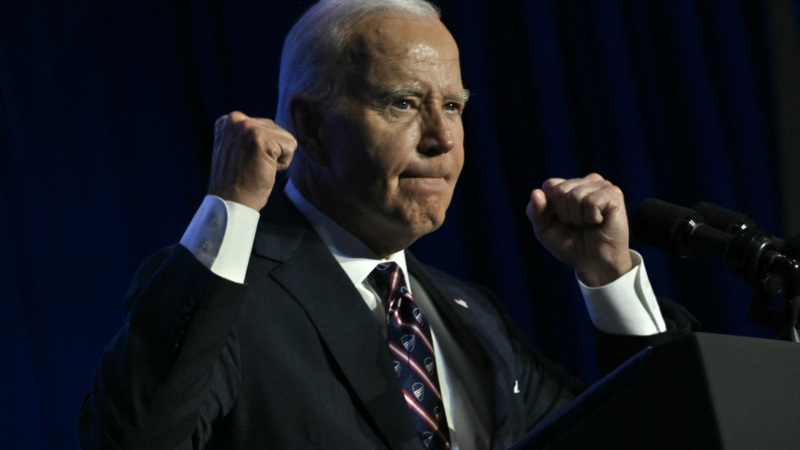

How Biden is getting used to life as a lame duck president

President Biden has been receding from the spotlight as the campaign marches on. But he still holds the highest office in the land for another four months and he’s is trying to make the most of it.

As early voting nears in Georgia, all eyes are on whether young voters will turn out

Gen Z and millennial voters make up nearly half of the eligible voting population in this year’s election. In Georgia, the race is on to get them registered before early voting begins this month.

In his hometown, Trump’s alleged would-be assassin acted like he was ‘above the law’

Neighbors in Greensboro say Ryan Routh, the man accused of pointing a rifle at the golf course where Donald Trump was playing, wasn't someone they knew well. But he was well-known to law enforcement.