From apps to gadgets, ‘Second Life’ considers how tech is changing having a baby

When journalist Amanda Hess was 7 months pregnant, a routine ultrasound revealed that her baby appeared to be sticking out his tongue. Hess was charmed by the visual, but her doctors warned that it might be sign of a rare genetic condition. What followed was a spiral of MRIs, genetic testing, consultations with specialists and late-night dive into the internet for answers.

“After several weeks of tests, when I was about eight months pregnant, we learned that my son has Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome [BWS], which is an overgrowth disorder that, among other things, can cause a child to have a very enlarged tongue,” Hess says.

BWS is a genetic condition that occurs in about one in 11,000 births. In addition to enlarged tongues, children with BWS may have enlarged abdominal organs and an increased risk of developing certain cancers during childhood.

Hess was frustrated that the app she had been using seemed to focus exclusively on healthy pregnancies — the BWS diagnosis fell beyond its scope. She turned to Google, but the search results weren’t reassuring. She read tabloid news stories and Reddit threads of people who were cruel about the existence of babies with the BWS. One influencer even suggested that the syndrome was caused by stressed out mothers who had figuratively bit their own tongues during pregnancy.

“It’s completely ludicrous,” Hess says. “I know that my son’s genetic condition was not caused by something I thought during pregnancy. But at the time, there was this sub-rational part of myself that really felt that that was true.”

When Hess’ due date finally came, she labored for 24-hours before her doctors recommended she have a C-section. That’s when she started crying; looking back now, she says her research into BWS had made her afraid to meet her son. But after his birth, those fears disappeared.

“He was a person, finally, who I had a real relationship with, all of these imagined images of him and potential lives for him dissolved,” she says. “And it was really only at that moment that I realized how disability can be so divorced from its human context through these technologies and how I really needed to just meet this baby in order to put it back there.”

Once I became pregnant, my relationship with technology became so much more intense. … It was only later that I really began to understand that these technologies work as narrative devices.

Amanda Hess

In the new book, Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age, Hess writes about how technology shapes every aspect of parenting — from our online identities to the pressures of sharing our lives in real-time.

“I started to think about writing a book about technology before I became pregnant, not sort of planning to focus it on this time in my life,” she says. “And then instantly once I became pregnant, my relationship with technology became so much more intense. … It was only later that I really began to understand that these technologies work as narrative devices, and they were working in my life to tell me a certain story about my role as a parent and the expectations for my child.”

Interview highlights

On pregnancy apps vs. traditional books on pregnancy

My phone was always there. And so even if I did not intend to bring my pregnancy app with me, it was there constantly. And so I found myself looking at it again and again. Also, a book is a set document. It covers a limited number of scenarios, and there’s, like, a real limitation to that. But it also means that it can’t be sort of tweaked and engineered so that it serves you some seemingly new piece of information like every day or every few hours. I found myself looking at [the pregnancy app] Flo during my pregnancy, like, 10 times a day, even though … I was not looking … for actual advice or real information. I wasn’t taking that information and changing my diet or my movements. I think I was looking for reassurance that I was doing OK. … And so there became this real intimacy to our pseudo relationship that I didn’t have with an informational pregnancy book.

On advanced prenatal and embryonic testing designed to predict disabilities and abnormalities

I think the thing that worries me the most about these technologies is there seems to be so much interest and investment in understanding what certain children will be like — and trying to prevent children with certain differences — and very little investment in the care for those children, research that could help these children and adults. And so I really found myself on both sides of this divide, where I had access to what was at the time some advanced prenatal testing, but was also able to see after my child’s birth that he was being born into a world that is not innovating in the space of accommodating disabilities in the way that it is innovating in the space of trying to prevent them.

On the potential impact of baby monitor surveillance

I think there’s this way that surveillance can become confused with care and attention and love. And I had this experience with my kids where I had installed this fancy baby monitor that I was testing out for the book, and through it … the video was uploaded to some cloud server, so I could watch them from anywhere. … But it wasn’t until one night when the camera was set up and I laid down with my son in his bed I sensed this presence in the corner of the room, these, like, four red glowing eyes. … I could really see it from his perspective. Like, he’s not seeing this beautiful smiling image of me watching him. He is seeing four mechanical eyes.

I spoke with my friend who had used a camera with her kid who eventually asked for it to be taken out when she was 3 years old or something and could articulate this because she didn’t want “the eye,” as she called it, to be watching her in her bedroom. And I think so many times these technologies are purchased by parents before their kids are even born. And they want to do what’s right and they’re scared and they want to make sure that they have everything they need, like before the child arrives. And so we’re not even giving ourselves a chance to really understand what it is we’re getting and whether we actually need it.

On the SNOO, a high-tech bassinet that responds to a baby’s cry with motion

I spent such a long time trying to troubleshoot the SNOO to try to get it to work for my baby, until eventually I found that I was really troubleshooting my child, and he had become so entwined with the technology that I really didn’t know where the workings of the machine ended and where my son’s sleep patterns began. And so this technology that’s often sold as a tool to help us better understand our kids and get data insights into them, in this case, for me, it actually made it more difficult for me to understand what was going on with him and how he really wanted to sleep.

On finding support from online communities and forums about BWS

Just seeing the thousands of people who are members of these groups and seeing those numbers is so comforting to me because it reminds me that my son is not alone. We were not alone with him. There is this whole community of people who look the same in some way. They experience some of the same social stigmas. They experience some of the same medical traumas and medical experiences. They just don’t exist in a geographical community because the condition is too rare. So these groups are a real reminder for me that the internet can be such a balm to communities of people who can’t access each other offline.

Sam Briger and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Transcript:

TONYA MOSLEY, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. Today, I am joined by Amanda Hess. She’s a journalist, cultural critic, and now author of a new memoir titled “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” The book starts with a moment every expecting parent dreads, a routine ultrasound that is suddenly not routine. When Hess was 29 weeks pregnant, doctors spotted something that indicated her baby could have a rare genetic condition. What followed was a spiral of MRIs, genetic testing, consultations with specialists, and, like many of us would do, a late-night dive into the internet for answers.

That search led her down a rabbit hole into fertility tech, AI-powered embryo screening, conspiracy theories, YouTube birth vlogs, the performance of motherhood on Instagram, and threaded through it all, an unsettling eugenic undercurrent suggesting which children are worth having. Known for her commentary on internet culture and gender at The New York Times, Hess turns her critique inward, asking herself, what does it mean to become a parent while plugged into an algorithmic machine that sorts scores and sells versions of perfection and what’s considered normal? Amanda Hess, welcome to FRESH AIR.

AMANDA HESS: Thank you so much for having me.

MOSLEY: You opened this book with a moment that I mentioned soon-to-be parents’ fear – that’s a routine ultrasound that shows a potential abnormality. And at the time, you were seven months pregnant. What did the doctor share with you?

HESS: He told me that he saw something that he didn’t like, and that phrase has really stuck with me. But what he saw was something that, when I saw it, I thought was cute, which is that my son was sticking out his tongue. And that’s abnormal if the baby is, like, not just bringing the tongue back into the mouth. Although, of course, I didn’t know that at the time. After, you know, several weeks of tests, when I was about eight months pregnant, we learned that my son has Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, which is an overgrowth disorder that, among other things, can cause a child to have a very enlarged tongue.

MOSLEY: One of the things you do in your writing that’s really powerful is you integrate the ways that technology really infiltrates every waking moment of our lives, including this particular moment when the doctor looked at your ultrasound. And I’d like for you to read about this moment just before you receive that news from the doctor. You’re on the sonogram table. You’re waiting for the doctor to arrive. And as you’re lying there with that goo that they put on your stomach to allow for the ultrasound wand to glide over your pregnant belly, your mind begins to race. Can I have you read that passage?

HESS: Sure. (Reading) The errors I made during my pregnancy knocked at the door of my mind. I drank a glass and a half of wine on Marc’s birthday before I knew I was pregnant. I swallowed a tablet of Ativan for acute anxiety after I knew. I took a long, hot bath that crinkled my fingertips. I got sick with a fever and fell asleep without thinking about it. I waited until I was almost 35 years old to get pregnant. I wanted to solve the question of myself before bringing another person into the world, but the answer had not come. Now my pregnancy was, in the language of obstetrics, geriatric.

For seven months, we’d all acted like a baby was going to come out of my body like a rabbit yanked from a hat. The same body that ordered mozzarella sticks from the late-night menu and stared into a computer like it had a soul, the body that had just a few years prior snorted a key of cocaine supplied by the party bus driver hired to transport it to medieval times. This body was now working very seriously to generate a new human. I had posed the body for Instagram, clutching my bump with two hands as if it might bounce away. I had bought a noise machine with a womb setting and thrown away the box. Now, I lay on the table as the doctor stood in his chamber rewinding the tape of my life.

My phone sat on an empty chair 6 feet away. Smothered beneath my smug maternity dress, it blinked silently with text messages from Marc. If I had the phone, I could hold it close to the exam table and Google my way out. I could pour my fears into its portal and process them into answers. I could consult the pregnant women who came before me, dust off their old message board posts, and read of long-ago ultrasounds that found weird ears and stuck-out tongues. They had dropped their babies fates into the internet like coins into a fountain, and I would scrounge through them all, looking for the lucky penny for the woman who returned to say, it turned out to be nothing. Trick of light.

MOSLEY: Thank you so much for reading that, Amanda. I think that every soon-to-be mother, every mother, can really identify with that. And I think just in life. Like, we’ve come to this place with our relationship with technology that we can kind of Google our way out of tough moments. You write about receiving that first alarming warning of this abnormal pregnancy and how, even before getting a second or third opinion that clarified this diagnosis, your mind didn’t jump to something you did, but to something that you were. And that moment seemed to crystallize kind of this deeper fear about your body and how it surveilled and judged, especially in pregnancy. Can you talk just a little bit about how technology also kind of fed into your judgment about yourself?

HESS: Yeah. You know, I started to think about writing a book about technology before I became pregnant, not sort of planning to focus it on this time in my life. And then, instantly, once I became pregnant, my relationship with technology became so much more intense, and I really felt myself being influenced by what it was telling me. I’m someone who – you know, I understand that reproduction is a normal event, but it really came as a shock to me when there was a person growing inside of me, and I felt like I really didn’t know what to do. And so I also, you know, early in my pregnancy, didn’t want to talk to any people about it. So I turned to the internet. I turned to apps. Later, when my child was born, I turned to gadgets. And it was only later that I really began to understand that these technologies work as narrative devices, and they were working in my life to tell me a certain story about my role as a parent and the expectations for my child.

MOSLEY: I want to go back a little bit to deepen what you’re saying here to that undercurrent of – I think you used the term in the book – maternal impression that creeps into modern medicine, this notion that your thoughts and feelings and anxieties can physically mark your child. In your case, as you are on the internet, you’re reading, you’re connecting with other would-be mothers and mothers, your medical chart flagged the single dose of Ativan that you took early in your pregnancy as teratogen exposure, with that root terata meaning monster. And Ativan, I should note, is this anti-anxiety medicine that you took during this moment when you were really stressed out with work.

You wrote, actually, when I decoded its medical terminology, it said that I had created a monster. Now, two things that stood out to me about this. First, I hadn’t considered how blame and guilt are almost baked into the medical system just through terminology. And I also wondered, once that doctor said that thing to you at seven months when you were on the table, did you have to convince yourself that you didn’t cause your son’s condition?

HESS: I mean, I think I just assumed I did until much later, when I started to feel as if it didn’t really matter how it happened, that I had created my son, and he was wonderful, and I was capable as his mother. But I carried that idea with me for such a long time. I think what was so clarifying about looking up the medical terminology was that hundreds of years ago, there was this idea of the maternal imagination or the maternal impression, which is a pseudoscientific idea that a pregnant woman can, you know, see a monkey in the zoo and her child will come out with, like, apelike traits, or that she could see some kind of monstrous thing and that her child will come out to resemble a monster. And this was an explanation for birth defects.

And I found that even though all of those ideas had been, you know, discredited, there was still this undercurrent of blame that was really palpable to me. And I even found that, at a certain point, you know, after my pregnancy had been flagged as high risk and fetal abnormalities had been found in my son, it was me and my pregnancy that became the thing that people with normal pregnancies were advised to avoid. So I would read antianxiety books that said, you know, don’t spend time thinking about pregnancy complications because they’re quite rare. And so…

MOSLEY: As if you could do that, like.

(LAUGHTER)

HESS: Right? And so I – you know, I, too, had anxiety, and I also had pregnancy complications. And so I felt sort of like I had been brought along on this journey, this highly feminized journey that was supposed to, like, bring all pregnant women along and tell them what to do. And then, you know, suddenly, I had been cast out, and I had to sort of scurry over to a different part of the internet.

MOSLEY: You encountered, though, on the internet that pseudoscience with these fringe theories. You actually encountered this influencer who suggested that your stress in life or you figuratively biting your tongue might have actually caused your baby’s enlarged tongue.

HESS: Yeah, that’s true. There’s certainly still pseudoscientific practitioners working, maybe, you know, more so this week than last week. I don’t even know. But I did find someone who believes that things like cancer, even, like, the flu, COVID are caused by internal conflicts. And there was something about that, even though that’s completely false and total nonsense. Understanding that that was a cultural idea that this person was crystallizing and promoting really helped me to forgive myself because when you put it that way, like, it’s completely ludicrous. I know that my son’s genetic condition was not caused by something I thought during pregnancy. But at the time, there was this subrational part of myself that really felt that that was true.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, I’m talking to author Amanda Hess about her new book, “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE INTERNET SONG, “STAY THE NIGHT”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. And today, I am talking to Amanda Hess. She’s a journalist, cultural critic and author of the new memoir, “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” In the book, she explores how the deeply personal experience of becoming a parent collided with the algorithmic world of apps, surveillance tech and influencer culture. Amanda is a critic at The New York Times, where she covers internet culture, gender and language for the arts section in The New York Times Magazine.

Can you describe this part of the internet that you felt relegated to once you received your son’s diagnosis?

HESS: Yeah. You know, I spent the beginning part of my pregnancy using an app called Flo. And Flo presents you with this CGI kind of fetus poppet that looks like a very cute prebaby, and it’s floating around in this, like, ethereal mist. And again, it sounds so ludicrous, but when I was holding that in my hand, it felt on some emotional level like I was looking at my baby. And then, you know, once doctors began to find some abnormalities on the actual medical portal to my body in the ultrasound, I realized that, of course, this image that Flo had promoted to me was a lie. It has no special insight into the baby inside of me, obviously. And I also came to understand that it promotes this idea to all of the hundreds of millions of people who use it during pregnancy that that is what their baby ought to look like. That is what they should expect their baby to look like. And once I realized that wasn’t the case, you know, I wanted to see images of people like my son. I wanted to understand what his life would be like, and I wanted to understand what my life would be like as a caretaker for him.

So I started deep Googling Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and what I found was a lot of tabloid news of the weird reports about children born with extra-large tongues. I found Reddit threads from people who were quite cruel about the very existence of these babies. I found parents of children who had the condition, who were asking for funds for medical care or presenting their children’s lives, trying to raise awareness of it and look for acceptance. And I found the response to those people ranged from appreciation to disgust.

And it was not until my son was born – I remember two minutes before my son was born, my doctor finally recommended that I have a C-section. And after, like, 24 hours of labor or something, I was ready for it. But I cried, and I realized that I was crying because I was afraid. I was afraid to meet my son. And the minute I did, like, and he was a person, finally, who I had a real relationship with, all of these imagined images of him and potential lives for him dissolved. And it was really only at that moment that I realized how disability can be so divorced from its human context through these technologies and how, like, I really needed to just meet this baby in order to put it back there.

MOSLEY: This part of the book was really moving to me because what you’re really grappling with as well is, like, the value of information now at our fingertips, because on one hand, you received that scary ultrasound and these tests. And then you were able to dig through the internet and find all of these cases, which I’m sure when you talk to doctors about them, they would say, like, well, those are the most extreme cases – that’s why people are writing about them on the internet.

But then it puts you in kind of, like, this really profoundly tough position to be in because it’s divorcing you from that innate part of motherhood that comes with acceptance and understanding, and then you being able to move into motherhood with the knowledge that you know. Did you ever wonder if you had known, say, like, at 10 weeks or earlier, might you have felt the pressure to make a different choice of not to move forward with your pregnancy?

HESS: I’ve wondered that many times. One of the technologies that I write about in the book is the NIPT, which is a blood test of the pregnant person that can be done very early in pregnancy, as early as nine weeks. And there are now, you know, consumer versions of this test that are used to screen the blood for the potential appearance of certain genetic changes. And BWS is so rare. It’s found, I think at this point, in about 1 in 10,000 births that it really wouldn’t make sense to test every person for it.

But I remember asking a doctor, you know, could you do this really early in pregnancy? And she said, yeah, like, technically, you could. And I really fear thinking about who I was, as this very scared, newly pregnant person who felt insufficient to the job of parenting, that I would be influenced to consider abortion. And later in my pregnancy, I had an even scarier prenatal test that suggested that it was possible that the genetic abnormality in my child was catastrophic. And, you know, I was steeling myself for abortion at that point, too. It was not catastrophic. There was not a brain abnormality like I had feared.

I was so grateful that there were just a few places in the United States that I could have sought an abortion had I needed or wanted to. And so nothing about this experience has made me question my feeling that abortion should be available to any person who needs or wants it in any context. But I do have this new understanding of the context in which these decisions are being made, and I think that context is really lacking. And so it’s not the availability of abortion. It’s not even the availability of some of these prenatal tests.

Ultimately, I was really glad that my son was diagnosed before he was born because it meant that his doctors could be waiting for him right when he came out. But I also understood only then that these choices are being made in a culture that highly stigmatizes disability and that expects women to sacrifice everything about themselves and their body in the pursuit of creating a healthy, which I think is a euphemism for normal, child. And it’s that context that I hope we can challenge.

MOSLEY: Our guest today is author and cultural critic Amanda Hess. We’re talking about her new book, “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” We’ll be right back after a short break. I’m Tonya Mosley, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF DANIELE DI BONAVENTURA’S “LA MIA TERRA – INSTRUMENTAL”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. And if you’re just joining us, I am talking with Amanda Hess, journalist, cultural critic and author of “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” The book explores how the intimate, often disorienting experience of new parenthood is shaped and sometimes distorted by the digital world, from fertility apps and AI screening to influencer moms and surveillance tech. Amanda is a critic at The New York Times, where she writes about internet culture for the arts section and contributes regularly to The New York Times Magazine, covering gender and language.

I want to talk a little bit about how tech elites are investing in ways to optimize babies. And you actually began to see threads of this early on with that app that you mentioned earlier called Flo, which you started using as a period tracker, and then it evolved to become a pregnancy tracker, which had message boards, kind of operated like this place for perfect pregnancies, it sounds like.

HESS: Yeah, I think there’s a mode that these apps are working in, which is habituating people to having their bodies and their reproductive activities tracked in order to ostensibly improve them in some way. So as I was using Flo, you know, not only did it present me this idealized, cute, able-bodied fetus. It was feeding me information about what I ought to do, the actions I should take, the things that I should eat in order to ensure that I had this ideal pregnancy.

MOSLEY: And when you tried to talk about your son’s condition, though, what did you encounter on those message boards in particular?

HESS: As soon as I had an abnormal ultrasound and my pregnancy was recategorized as high risk, I started searching for those terms within Flo’s message boards, and they said, I’m sorry. Please try searching for something else. And so I felt like even in this subtle way that the app was programmed, I was being told that, like, my pregnancy had no space in that community.

MOSLEY: Is there something inherently different about an app and us being able to hold these technologies, you know, in the palm of our hand and constantly have access to them? You know, I’m thinking about when I was a pregnant person, and I just had all the books around what to expect when you’re expecting and other types of text that – some of them were written by men. Some of them were written by pseudo scientists, all of these things, but I saw them as resources, but not places of fact and understanding. Is there something inherently different about our relationship when it is presented to us in the form of technology that has a different effect on us?

HESS: I think so. I had books, too, and, you know, the first difference I noticed is that I wasn’t carrying this, like, big pregnancy book everywhere I went.

MOSLEY: Right, right.

HESS: But my phone was always there. And so even if I did not intend to bring my pregnancy app with me, it was there constantly. And so I found myself looking at it again and again. Also, a book is a set document. It covers a limited number of scenarios, and there’s, like, a real limitation to that. But it also means that it can’t be sort of, like, tweaked and engineered so that it serves you some seemingly new piece of information, like, every day or every few hours. I found myself looking at Flo during my pregnancy, like, 10 times a day, even though – I think this is so sick, but I was not looking to Flo for actual advice or real information. I wasn’t taking that information and changing my diet or my movements. I think I was looking for reassurance that I was doing OK. And so even if I wasn’t doing exactly what this app had said, I wasn’t missing something major. And there was someone, it really felt like, along with me who was keeping track. And so there became this real intimacy to our pseudo relationship that I didn’t have with, like, an informational pregnancy book.

MOSLEY: That sense of reassuredness (ph), too – I want to talk a little bit about, like, the privilege in that because on the face of it, it’s like the ability to know and understand. That all seems positive. I’m thinking about, like, some of the big technologies that are coming into fruition now or are already there, like OpenAI, Sam Altman’s funding of the genomic prediction, which is supposedly going to offer embryo tests predicting everything from diabetes risk to potential IQ of a baby. But you actually point this out in the book, that there is a growing divide because on one side, there are these affluent parents who have access to this kind of screening, and then on the other, many parents can’t even get basic access to prenatal care.

HESS: Right.

MOSLEY: How did your experience kind of help you reflect on those extremes?

HESS: You know, I think after the particular circumstances of my pregnancy, I became really interested in prenatal testing and how it was advancing and interested in the fact that it was so – it seemed like such an exciting category for all of the male tech leaders that we know so much about now. And, you know, it was only through, like, reading about them a little bit that I came to understand that this new ascendant technology that offers what they call polygenic analysis of embryos – so, you know, different outlets promise to find different characteristics. But they’re offering everything from screening that predicts an increase in IQ points, that screens for hereditary cancers, all of this stuff. It’s something that you can only use if you’re going to go through IVF. And so after paying for this embryo screening, which is a few thousand dollars, you’re also choosing to go through in vitro fertilization, which is not only just a really difficult experience for many people, but extremely expensive and out of reach for most people.

And as I was reading one story about this, I was really struck by a woman who founded one of these companies, who told one of her investors that instead of going through IVF herself, she should simply hire a surrogate and have her do it for her. And that, to me, really crystallized this idea of, like, a reproductive technology gap. I think the thing that worries me the most about these technologies is, again, there seems to be so much interest and investment in understanding what certain children will be like and trying to prevent children with certain differences and very little investment in the care for those children, research that could help these children and adults. And so I really found myself on both sides of this divide, where I had access to what was at the time, you know, some advanced prenatal testing, but was also able to see after my child’s birth that, you know, he was being born into a world that is not innovating in the space of accommodating disabilities in the way that it is innovating in the space of trying to prevent them.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, I’m talking to author Amanda Hess about her new book, “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF NONAME SONG, “BALLOONS”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley, and today I am talking to Amanda Hess. She’s a journalist, cultural critic and author of the new memoir, “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.”

I want to talk a little bit more about our presentation online and also kind of this idea of surveillance. So your work as a cultural critic – you often touch on surveillance, both state and personal. And in this book, you describe how new parents also surround themselves with surveillance tech, so baby monitors and nursery cameras that are constantly watching. And, of course, in our daily life, we’re all under so many forms of surveillance. How do you think this surveillance culture is affecting us? Or how did it affect you in those early days as a mother when you’ve got that baby monitor in your baby’s room? Like, are we habituating our children to be watched 24/7?

HESS: I think we are. I mean, I had this experience of during pregnancy habituating myself to some external authority watching my pregnancy. And then after my child was born, I became the authority who was watching him and surveilling him. And I think there’s this way that surveillance can become confused with care and attention and love. And I had this experience with my kids, where I’d installed this fancy baby monitor that I was testing out for the book, and the video was uploaded to some cloud server, so I could watch it from anywhere. I could watch them if they were taking a nap in their crib, but I was at the coffee shop down the street or whatever, and somebody else was there with them. And it could make it seem as if I were close to them because I would see my adorable children and have this experience of being able to just watch them sleep peacefully, which is so different from the experience of dealing with them most of the time.

But it wasn’t until one night when the camera was set up, and I laid down with my son in his bed, and I sensed this presence in the corner of the room – these, like, four red glowing eyes. And I really…

MOSLEY: You could see it from his perspective.

HESS: Yes.

MOSLEY: Right.

HESS: Then I could really see it from his perspective, and, like, he’s not seeing, you know, this beautiful, like, smiling image of me watching him. Like, he’s seeing four mechanical eyes. And I spoke with my friend who had used a camera with her kid, who eventually – she asked for it to be taken out when she was 3 years old or something and could articulate this because she didn’t want the eye, as she called it, to be watching her in her bedroom. And I think, you know, so many times these technologies are purchased by parents before their kids are even born, and they want to do what’s right, and they’re scared, you know, and they want to make sure that they have everything they need, like, before the child arrives. And so we’re not even giving ourselves a chance to really understand what it is we’re getting and whether we actually need it.

MOSLEY: Right. I mean, this goes back to, like, your ability to control the situation. I remember there was a time when, I think, our baby monitor went out in the middle of the night. So I woke up, like, from a deep sleep. It’s 8 o’clock. I’m like, wow, we slept for, like, eight, nine hours. And I realized that the baby monitor had died. And…

HESS: Yeah. That’s happened to me, too.

MOSLEY: I was – OK. I was completely freaked out. Like, (gasping) what if I missed, like, a catastrophe that happened? But then…

HESS: Yeah.

MOSLEY: …When you think back, it’s like, OK, if that were the situation, I would have heard it. I mean, I have my senses. Do you feel like these technologies, in many instances, kind of take us outside of ourselves from – we’re, like, giving control over to the technology?

HESS: Yeah, I had this experience with my son, where I heard about a robotic crib called the SNOO. Before he was born, I got this secondhand version off of a parental LISTSERV and set it up before he was born. So it was just sitting there, waiting for him to come sleep in it. And the SNOO, you know, promises that SNOO babies tend to sleep one to two hours more than other babies, which is such a tantalizing promise to a new parent.

MOSLEY: Yes. Right.

HESS: Like, one to two hours is so many hours…

MOSLEY: (Laughter) Extra. Right, yeah.

HESS: …For a parent of a newborn.

MOSLEY: The dream.

HESS: And my son just really didn’t take to the SNOO. And I spent such a long time, like, trying to troubleshoot the SNOO to try to get it to work for my baby until eventually, I found that I was really, like, troubleshooting my child. And he had become so entwined with the technology that I really didn’t know where the workings of the machine ended and where my son’s, you know, sleep patterns began. And so this technology that’s often sold as a tool to help us better understand our kids and get, like, data insights into them, in this case, for me, it actually made it more difficult for me to understand what was going on with him and, like, how he really wanted to sleep.

MOSLEY: So now you’re a mother of two. When you wrote this book, you started off with the pregnancy and birth of your first. This book is called “Having A Child In The Digital Age.” That’s the subtitle. How are you feeling about the future of raising a child in the digital age? Do you see, like, any positive trends in digital culture for the next generation, or do you kind of worry about these issues that we’ve talked about? Will they only intensify? Where are you on this now?

HESS: Yeah, I mean, I think that’s the thing that I don’t want to think about is just that very soon, like, my kids will have access to devices, whether it’s at school or in our home, where they can just, like, log on themselves and see what’s out there. It’s something that I’m just, like, not prepared to deal with at the moment. There are, like, a couple of things that I was so grateful to have access to during my pregnancy that I hope will be helpful for my kids. And one was, you know, groups that are dedicated to the particular rare disorder that my son has, where people who have the syndrome or family members who are caretakers can come together and just talk about their experiences.

And just seeing the thousands of people who are members of these groups and seeing those numbers is so comforting to me because it reminds me that, like, my son is not alone. We were not alone with him. There is this whole community of people who have – you know, they look the same in some way. They experience some of the same social stigmas. They experience some of the same medical traumas and medical experiences. They just don’t exist in a geographical community because the condition is too rare. So these groups are a real reminder for me that the internet can be such a balm to communities of people who can’t, you know, access each other offline.

And similarly, like, I think the disability justice community is such, like, a wonderful community that I hope that my son, whether he ends up identifying as disabled or not, has some access to. And that is really helped by just the accommodation of being able to meet online. And so I think there are so many ways that my kids could find solace there. But I really think we’re so robbed of the ability to understand what good technology would look like because technology is not, for the very most part, being developed for the betterment of human beings. It’s being developed to drive profits.

And so all of these, like, wonderful parts of online communities are embedded in that capitalist structure, and they’re held hostage by it. And so I really think, to the extent – like, I don’t think phones are the problem. I don’t think the internet is the problem. I think these devices are indicative, unfortunately, of much larger problems. And it’s really going to take, like, the socialization of technology in order for us to really understand its potential as, like, something that’s positive for us and our children.

MOSLEY: Well, Amanda, I really appreciate you writing this book. And thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us about it.

HESS: Thank you so much.

MOSLEY: Amanda Hess is a journalist, cultural critic and author of the memoir “Second Life: Having A Child In The Digital Age.” Coming up, book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews Daniel Kehlmann’s latest novel, “The Director.” This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ALFREDO RODRIGUEZ’S “VEINTE ANOS (TWENTY YEARS)”)

A new Nepali party, led by an ex-rapper, is set for a landslide win in parliamentary election

A Nepali political party led by an ex-rapper is set for a landslide victory in the country's first parliamentary election since Gen Z protests ousted the old leadership that has ruled the Himalayan nation for decades.

U.S. Judge says Kari Lake broke law in overseeing Voice of America

He declared all of Lake's actions over the past year to be null and void, including the layoffs of more than 1,000 journalists and staffers.

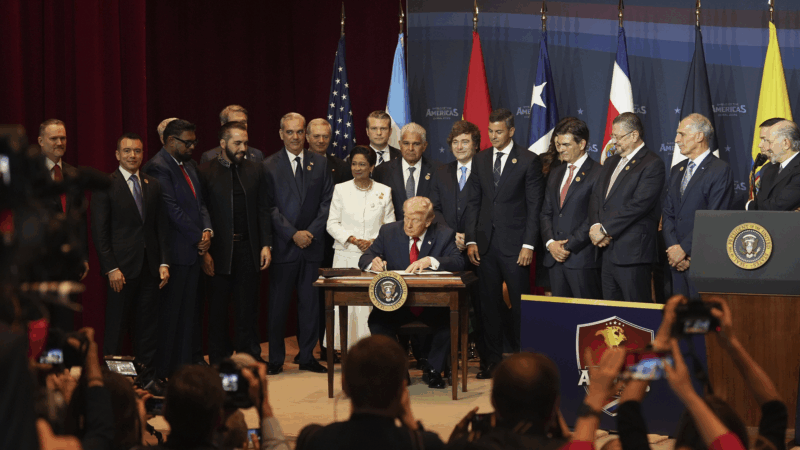

Trump vows to ‘take care of Cuba,’ praises Venezuela cooperation at summit

Trump made the promise in front of an assembled meeting of Latin American leaders.

British Columbia to make daylight saving time permanent

The Canadian province is permanently ending the biannual time shifts for more light at the day's end. But research shows daylight saving increases health risks.

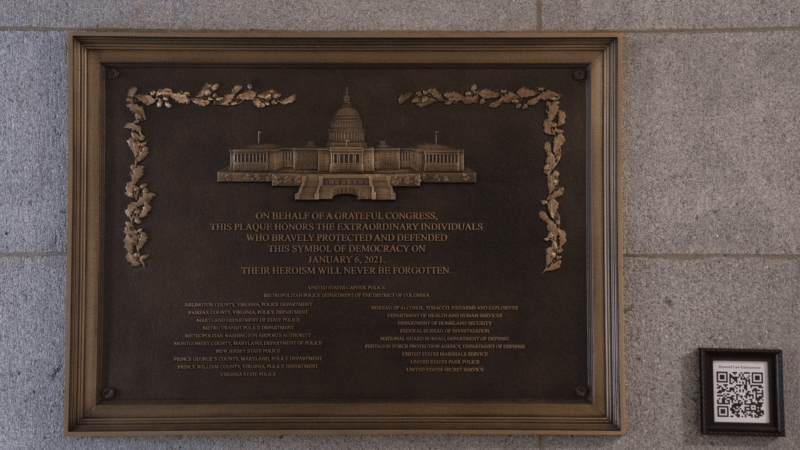

Jan. 6 plaque honoring police officers is now displayed at the Capitol after a 3-year delay

Visitors to the Capitol in Washington now have a visible reminder of the siege there on Jan. 6, 2021, and the officers who fought and were injured that day.

Authorities searching debris after suspected tornadoes kill 6 in Michigan, Oklahoma

A 12-year-old boy is reported to be among the dead following powerful storms that stretched across the middle of the country.