Country singer Charley Crockett is ‘afraid of getting fenced in’

Charley Crockett spends so much time on the road, he says he sleeps better on his bus than on a real bed.

“That big diesel motor sings me lullabies at night,” he says. “It really is comforting to me. You know, the low hum of the motor and the satellite television, turned down low on some old-time movie.”

In the last year, Crockett played more than 100 shows — in Australia, Canada, the U.K. and all over the U.S. And his preference for the bus, he says, explains why there isn’t a whole lot in this dressing room backstage at the Yaamava’ Resort & Casino in San Bernardino. The counters are sparse — a bottle of mezcal, a bowl of lemons and ginger, a bag of tortilla chips and a case of Topo Chico.

“I take the lemon and I just squeeze it into my mezcal there,” he says. When asked if the mezcal is good for his singing voice, he replies: “Yeah, let’s go with that.”

Outside the dressing room, in a hallway lined with signed cymbals, his wardrobe trunks are cracked open, filled with exquisitely preserved vintage Western wear — a collector’s dream. There are Pendleton and houndstooth jackets, and smooth golden leather ones with fringe and elaborate stitching. He pulls out a box of beautiful tan cowboy boots, with cream-colored rodeo riders in mid-flight on the side.

“I bet I paid too much for these,” he says. “I started dressing up on the street in New Orleans. And the main reason was, being [the] hobo that I was, I started dressing up so the tourists would take me serious, you know? Back then, I was wearing wingtip shoes and old newsboy caps. I used to do a little jig for the tourists in front of Café Du Monde.” He breaks out into a jig in the carpeted hallway. He’s still got it. “I was a song-and-dance man.”

Crockett is still a song-and-dance man. But he’s come a long way since his days busking on the streets of New Orleans. Now, he performs at theaters in front of thousands of people. He’s graced the stage at Nashville’s legendary Ryman Auditorium, and he’s jammed with Willie Nelson. He even got married at Willie Nelson’s Luck Ranch last year. To cap it all off, he’s up for his first Grammy, for Best Americana Album, for his record $10 Cowboy.

Crockett says family lore links him to the frontiersman and politician Davy Crockett — “Son of Davy” is written on big red letters on his touring truck. He was born in the state where Davy died, in San Benito, Texas, just miles from the Mexican border in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. He spent his early years living near there, in a single-wide trailer with his mom, among grapefruit and orange groves, cotton and sugarcane.

Crockett recalls being influenced at an early age by The Johnny Canales Show — the musical showcase helmed by the eponymous Tejano singer — and Crockett says he used to get up on a milk crate, sporting a cape, swing his arm and shout “Take it away!” to repeat the host’s signature line.

When he was 8 or 9, his mom moved them up to the Dallas-Fort Worth area. It was around then that he began to spend summers down in New Orleans. He lived with his uncle, who worked as a bouncer at strip clubs on Bourbon Street, dealt cards at casinos and worked the bingo halls.

“I was seeing the culture of the French Quarter when I was 8, 9 years old,” Crockett recalls. When he was older, he started playing and singing on the streets there. “And it really was in New Orleans where I learned all the different styles. I learned drinking songs, playing in front of tourists on Royal Street. I got a sense of jazz timing, of how to really strum a guitar, how to pick a guitar to a two-beat, to a shuffle. I’m not a jazz musician by any stretch, but I learned some jazz positions to substitute in for simple country and blues chords, there on those streets, you know?”

It was also in New Orleans that he says he learned to play for an audience; how to entertain and talk to crowds — a skill that he finessed in New York City, playing in the parks.

“I was playing in the spot nobody wanted,” he says. “And then slowly but surely, over a couple of years, I started getting better, you know, because I was playing 10 hours a day. But I couldn’t compete with the noise of the traffic, just one young man and a guitar. It pushed me underground.”

Underground, to subway platforms and inside train cars. He began performing with a group that called itself “Train Robbers,” and in one video, you can see Crockett, in a beanie and black T-shirt, singing soulfully as his friend Jadon Woodard raps between verses.

Performing in New York brought other opportunities. He drifted to California, Colorado, Copenhagen, Paris and Morocco to busk. But the farther he got, he says, the more he felt his Texas roots showing.

“I think I was running from Texas for a long time. Eventually, you run far enough from home that you realize at some point that, even in trying to get away from it, it tells you who you are.”

They laughed at me in New York City

Called me a fool in L.A

I doubt that Nashville saw me coming

Besides the bar folks working late

Played every room in the state of Texas

All the ones in California too

So many nights I can’t remember

Maybe I’ve played a song for you

Left San Francisco in a hurry

They ran me out of Fort Worth town

Been to the bottom of New Orleans

Them river boats make a lonesome sound

— “Good at Losing,” from the album $10 Cowboy

As he takes the stage for the soundcheck at the Yaamava’ Theater, he’s sporting a pale buckskin jacket, plaid Western shirt and relaxed fit jeans. He’s got on a big white cowboy hat, and his initials loom large over the band, the two Cs sideways horseshoes, studded with lights.

In addition to Crockett’s exhausting tour schedule, he’s released a prolific amount of music. He’s put out 15 records in the last nine years, all on his own label, Son of Davy. In March, he’s putting out another, Lonesome Drifter, co-produced by Shooter Jennings, the son of Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter.

In the middle of it all, in 2019 he underwent open-heart surgery, for a potentially fatal heart valve problem. But even that hasn’t slowed him down.

“I think with my heart surgery, when I woke up on the other side of it, it’s not the pain or the scar on my chest — it was that all of a sudden I realized that I was going to die,” he says of what he took from that.

If anything, it’s made him work harder. He’s afraid to stop, he says.

“I guess I’m afraid of getting fenced in, you know? As you move further into this business, the ticket sales go up. The ticket price goes way up. I can tell you, it puts a pressure on you to be like, ‘Well I need to do something more.'”

It sounds a bit like he’s saying “making it” as an artist means constantly feeling inadequate — like you’re not enough.

“I didn’t mean to put it like that. But I mean, you could just say that’s what it feels to be American, right? That’s what we’re taught to do. You know you got to work. You got to swing that hammer. And you know what? I’m not mad about that. I’m gonna keep swinging that f***ing hammer,” he says.

It might even win him a Grammy.

“I’ll give it to my mama if I ever get one.”

Ailsa Chang and Kira Wakeam contributed to this story.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

The music industry’s biggest night is coming this Sunday – the Grammy Awards. And this week, as we do every year, we’re bringing you the stories of a few first-time Grammy nominees. We’re going to kick things off in San Bernardino, at the Yaamava’ Resort and Casino…

CHARLEY CROCKETT: You just got it on the one (ph)?

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: No, we’re good.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: Yeah.

CHANG: …Where we caught up with country music singer Charley Crockett in the middle of his soundcheck.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “HEY MR. NASHVILLE”)

CROCKETT: (Singing) Hey, Mr. Nashville, out there on the town. You wine ’em and dine ’em and hand ’em a plastic crown.

CHANG: Crockett was born and raised in Texas, grew up in a single-wide trailer with his mom and says his family lineage traces all the way back to the frontiersman Davy Crockett. Well, now Charley Crockett is up for best Americana album for his record “$10 Cowboy.” I was so excited to meet him, I showed up in one of my several cowgirl outfits.

Charley, I want you to take note. I wore my boots for you. I wore my cowboy hat for you.

CROCKETT: Well, you wear it well.

CHANG: Thank you so much. You wear it well, too, I have to say.

I mean, he does. Crockett exudes country cool – the white cowboy hat, the turquoise belt, the stubble. Oh, and don’t even get me started on all the gorgeous vintage country outfits he takes on the road with him.

Wow. Your costumes are in, like, a vault.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOOR SLAMMING)

CHANG: (Laughter) Do you have a favorite jacket or…

CROCKETT: Yeah, I wear…

CHANG: …A jacket you forgot you owned?

CROCKETT: I wear this one a lot.

CHANG: Oh, I love the fringe on that.

CROCKETT: This one’s nice. You don’t even need to wear nothing under it. You just button it up.

CHANG: Ooh, look at the stitching on that. My dream would be to see you wear this jacket with the leather stitching tonight with the white flower boots.

CROCKETT: OK.

CHANG: But, you know, my dreams don’t always come true.

CROCKETT: (Laughter) I’m going to give it a shot. You know, when I first was getting off the street and out of the bars – I got my first agent – on the street in New Orleans, where I started dressing up. And the main reason was – is being, like, a hobo that I was, I started dressing up so the tourists would take me serious. I used to do a little jig for the tourists in front of the Cafe du Monde.

CHANG: But then you ended up preferring the street as your amphitheater. Like, you spent years playing in New York – right? – also on the subway platform, in subway trains?

CROCKETT: Yeah.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

CROCKETT: (Singing) Ooh, honey, how I try.

CHANG: What was that like? Like, I’m just sort of picturing this train barreling underneath Manhattan, and you’re singing country and blues. Did you feel a little bit out of place?

CROCKETT: Yeah, yeah. But, you know, I wanted to go to New York because of Bob Dylan, because I – of his songwriting. And then, slowly but surely, over a couple of years, I started getting better, you know, ’cause I was spending – I mean, I was playing 10 hours a day…

CHANG: Wow.

CROCKETT: …You know?

CHANG: That’s a lot of practice.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “GOOD AT LOSING”)

CROCKETT: (Singing) They laughed at me in New York City, called me a fool in LA. I doubt that Nashville saw me coming.

CHANG: But wait, go to the album covers ’cause I want to talk about that.

CROCKETT: Yeah.

CHANG: Your album covers have this really cool look – vintage, classic.

CROCKETT: Yeah.

CHANG: What is it that you’re trying to channel on these covers?

CROCKETT: I love the old records because they didn’t have all this digital streaming and…

CHANG: Yeah.

CROCKETT: …All this stuff. It was like, you had to tell the story with the picture to sell it to somebody, you know? You had to summarize what you were about in a short paragraph on the back of that thing…

CHANG: Yeah.

CROCKETT: …As much as they could stuff in there.

CHANG: Yeah. Well, you know, I hear it in your sound, too. Like, the arrangements in your albums, they hearken back to this older time in country.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “HARD LUCK AND CIRCUMSTANCES”)

CROCKETT: (Singing) Because it’s hard luck and circumstances that brought me here. And if they…

CHANG: How do you find the right balance between resurrecting an older style of music versus creating something new and different that you can completely call your own?

CROCKETT: Well, it’s funny you should say that ’cause I feel like I’m at this kind of crossroads or, you know, like, I’m in this kind of vortex. I’m all about making a statement more than a financial impact, right? But, like, let’s be honest here. Like, the agents, the publicists, the studios, the labels, they can tell you they’re about this, that and the third, but it’s just about money, right? And if you think it’s about something else, you’re going to get bruised.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHARLEY CROCKETT SONG, “HARD LUCK AND CIRCUMSTANCES”)

CROCKETT: I didn’t lobby for a Grammy. I refused to join the committees. I don’t advertise to consider me for the Grammys. I’m not about that. I don’t.

CHANG: Are you annoyed you got nominated?

CROCKETT: No, no, I’m honored. It’s great.

CHANG: OK.

CROCKETT: It’s great to be recognized. I’m just saying I don’t do it for that.

CHANG: But also, at this point in your career, I mean, you’ve played the Ryman, you’ve performed with Willie Nelson…

CROCKETT: Yeah.

CHANG: …You’ve toured all over the world. Like, what does a Grammy nomination mean to someone who’s already accomplished so much?

CROCKETT: Well, it means a whole lot to my mama.

(LAUGHTER)

CHANG: Maybe that’s enough, then.

CROCKETT: Yeah. Yeah. She’s proud of me for sure, you know?

CHANG: Something your mama might be thinking about is the pace of your life right now, though. I read, earlier in your career, the more you toured, the worse you felt. Like, you would get tired, dizzy, out of breath, and it turned out you had this potentially fatal heart valve problem. So you had open-heart surgery back in 2019. By the way, how are you feeling today?

CROCKETT: Oh, yeah. Well, I ain’t pushing up daisies yet.

CHANG: OK. But you are, like, not slowing down at all. I was looking, like, you – what? – you put out 15 albums in the last nine years. And then your tour schedule this past year, every single month you are performing somewhere. And we’re talking about, like, Australia, the U.K., Canada.

CROCKETT: I was out for four months straight last summer.

CHANG: So why are you moving at such a rapid, ferocious pace?

CROCKETT: Yeah, I don’t know, because all the people I ever related to, everybody is, like, working so hard their whole life. You kind of work so hard that, you know, you don’t have kind of time to stop and take it all in, you know? And…

CHANG: Are you afraid to stop?

CROCKETT: Yeah.

CHANG: Why?

CROCKETT: I would hate – I guess I’m afraid of getting fenced in. You know, as you move in – further into this business, you know, the ticket sales go up, the ticket price goes way up. I can tell you, it puts a pressure on you to be like, well, I need to do something more.

CHANG: Gosh. So you make it sound like making it as an artist means constantly feeling inadequate.

CROCKETT: (Laughter) Oh, I didn’t mean to…

CHANG: You’re never enough.

CROCKETT: …Put it like that, but I mean, you could just say that’s what it feels to be American…

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “AMERICA”)

CROCKETT: (Singing) America. I just keep working. Doesn’t matter how I feel. America, it’s been said that my whole life is in your hands.

…Right? That’s what we’re taught to do, you know? You got to work. You got to swing that hammer. And you know what? I’m not mad about that. I’m going to keep swinging that hammer. I’m just going to keep doing it.

CHANG: Well, keep swinging that hammer, Charley Crockett. And congratulations on your first Grammy nomination. No matter how you feel about…

CROCKETT: (Laughter).

CHANG: …The Grammys, seriously, congratulations.

CROCKETT: Yeah. I’ll give it to my mama if I ever get one.

CHANG: (Laughter) It was so great talking to you. Thank you.

CROCKETT: The pleasure was all mine.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “AMERICA”)

CROCKETT: (Singing) America, you know I can be hard to understand.

CHANG: Charley Crockett, up for the Grammy Award for best Americana album. Stay tuned this week as we meet more first-time Grammy nominees.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “AMERICA”)

CROCKETT: (Singing) I’m only a man.

UConn takes 12th NCAA women’s basketball title with dominant win over South Carolina

UConn is back on top of women's basketball, winning its 12th NCAA national championship by routing defending champion South Carolina 82-59 on Sunday.

Alex Ovechkin scores goal #895 to break Wayne Gretzky’s all-time NHL scoring record

The Washington Capitals star made history with a power play goal from the left faceoff circle — as Gretzky, who last set the record more than 25 years ago, looked on.

Severe storms and floods batter South and Midwest, as death toll rises to at least 18

Severe storms continued to pound parts of the South and Midwest, as a punishing and slow-moving storm system unleashed life-threatening flash floods and powerful tornadoes from Mississippi to Kentucky.

Israeli strikes on Gaza kill at least 32, mostly women and children

Israeli strikes on Gaza killed at least 32 people, including over a dozen women and children, local health officials said Sunday, as Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu headed to meet President Trump.

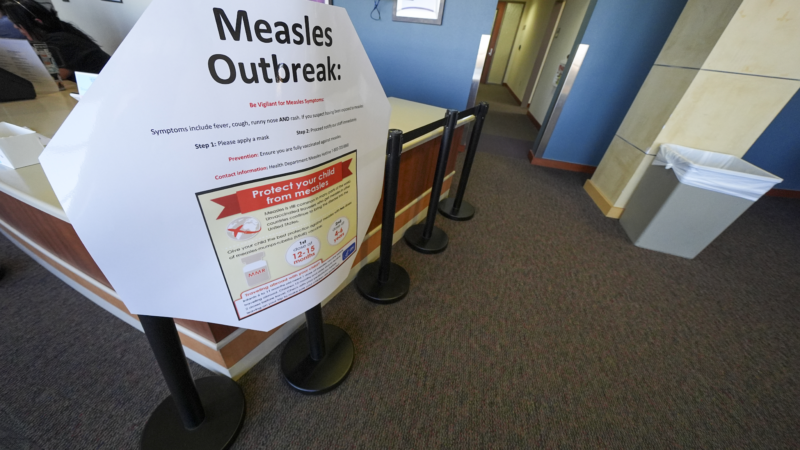

Second child dies from measles-related causes in West Texas, where cases near 500

A second school-aged child in West Texas has died from a measles-related illness, a hospital spokesman confirmed Sunday, as the outbreak continues to swell.

Yemen Houthi rebels say latest US strikes killed 2, day after Trump posted bomb video

Suspected U.S. airstrikes killed at least two people in a stronghold of Yemen's Houthi rebels, the group said Sunday.