Confused by ‘best by’ or ‘use by’ labels? The FDA wants your input to reduce food waste

The can of chickpeas in the pantry has a “best buy” date that passed two weeks ago. The loaf of bread on the countertop boasts a “sell by” date of today. And then there’s the Manchego cheese in the deli drawer, which comes stamped with an “enjoy by” date that’s just around the corner. So is it time to toss these groceries?

Probably not.

Many consumers believe date labels indicate when packaged foods are no longer safe to eat, but in fact that’s not correct. “All of those dates are really there for food quality. They aren’t there for safety,” says Donald Schaffner, a food safety expert at Rutgers University. After the date passes, “the food may not taste as good, but it’s still safe to eat.”

But many consumers don’t realize that – and this rampant confusion over what date labels mean leads to a lot of wasted food and money.

That’s why the FDA and USDA are currently asking the food industry and the general public for their input on how these food date labels are used and how they’re interpreted. The agencies say it’s part of advancing a national strategy to reduce food loss and waste.

Research has found that the vast majority of consumers — 84% — toss out food at least some of the time because of the date label, and 37% say they do it most of the time. The USDA estimates that the average family of four spends at least $1,500 each year on food that ends up uneaten. Other estimates suggest with food prices so high these days, an average household of four is now spending more than $3,000 a year on food that gets tossed out.

“It’s not only leading to food waste, but it’s also causing people to waste a lot of money,” says Emily Broad Leib, a food policy and food waste expert at Harvard Law School. The concerns around food prices have made food waste even more of a focus, she says. “People really want to be thoughtful about how they’re spending money on their household food.”

And it’s not just about money. Food waste ends up in landfills, where it is a major source of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, so it “has a really big environmental impact,” Broad Leib says.

California recently passed a law that requires the standardization of food date labels — “best if used by” indicating when food is at its peak freshness and “use by” for food safety concerns. Broad Leib says she’d like to see the federal government follow suit by requiring standardization of food date labels.

Right now, there is no federal regulation requiring the use of food date labels. The one exception is infant formula. By law, it’s required to have a “use by” date because its nutrient value declines over time, which could put infants at risk of nutritional deficiencies.

For several years, the FDA and USDA have been encouraging food manufacturers to voluntarily adopt the phrase “best if used by” for quality. Research conducted by Broad Leib and her colleagues has found that consumers are most likely to interpret this label correctly as an indication of quality, not safety. Many food companies also apply the term “use by” to signal when food should be discarded.

But adoption of this wording is far from universal. And many states have their own food date labeling requirements that actually make it difficult or impossible for companies to adopt this phrasing, Broad Leib says. She says the plethora of date label phrases being used contributes to consumer confusion.

In an email to NPR, an FDA spokesperson said for now, the agency is just gathering information and will use the input it receives “to inform any next steps on date labeling.” Here’s a link if you want to weigh in.

In the meantime, where does that leave consumers when deciding whether to throw out food? Schaffner says don’t rely solely on the date on the label, instead use your own judgement.

“The key message is that something doesn’t go from perfectly safe to completely toxic as soon as it passes that date,” Schaffner says. “It probably depends upon the food. It depends upon the individual and how sensitive they are.”

There are some foods that you have to be more careful about like deli meats or egg or chicken salad — those don’t stay good for long, Broad Leib says.

With other foods, you have more leeway. Take yogurt, for example.

“The rule of thumb that I use with yogurt is that in fact, it is already spoiled milk,” Schaffner says. “And so the only thing that is going to happen in your refrigerator is that it is going to become more spoiled. It might become more tart.” But as long as you don’t see any mold on it, he says yogurt is safe to eat beyond the date on the label.

With hard cheeses, he advises cutting about a quarter-inch around any mold you might see and throwing that away. But he says soft cheeses and jams that have grown moldy require more caution, because mold can penetrate more deeply, so it might be best to toss them. As for canned foods, if the can is not rusted or bulging, he says it’s probably fine to consume.

And obviously, if a food doesn’t smell or taste good, Schaffner says don’t eat it. “Life is too short to eat bad food.”

This story was edited by Jane Greenhalgh

Transcript:

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

At the grocery store, you might see a few different phrases on food labels – use by, sell by, best before. Many consumers are confused about what they actually mean. The FDA and USDA are asking the food industry and the public for their input on these date labels to clear up the confusion. NPR’s Maria Godoy is here to tell us more. Hi, Maria.

MARIA GODOY, BYLINE: Hi, Ari.

SHAPIRO: Why are there so many different date labels, and what do they mean?

GODOY: Well, there’s no real standardization on the use of these date labels. They’re supposed to indicate when the food is freshest – so when it tastes best. For the most part, they aren’t there to tell you when your food is no longer safe to eat. But that’s not what consumers think. You know, they tend to think it means it’s no longer good, and that leads to a lot of wasted food.

SHAPIRO: So people are throwing food away that has not gone bad just ’cause it’s past the date on the box or the bag.

GODOY: Exactly. So one study found 84% of consumers said they throw away food because of the date at least occasionally, and 37% do it pretty much all the time. And that’s not just a lot of wasted food. It’s a lot of wasted money. The USDA estimates the average American household spends at least $1,500 a year on food that gets tossed out. Other estimates put that number at more than $3,000 a year. You know, here’s Emily Broad Leib. She’s a food policy and food waste expert at Harvard.

EMILY BROAD LEIB: It’s not only leading to food waste, but it’s also causing people to waste a lot of money, which – I think it became even more of a focus for them because of the concerns around food prices right now.

GODOY: And it’s not just about money. Broad Leib points out that food waste ends up in landfills, where it’s a major source of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. So this is also an environmental issue.

SHAPIRO: So tell us about the proposals to make these labels more understandable, more consumer-friendly.

GODOY: Yeah. Well, many food companies have voluntarily adopted the use of the words best if used by to indicate when food is at its peak freshness and use by as a food safety date. But this usage isn’t universal at all. California recently passed a law that requires food products to use these two labels, so that’s brought more attention to the issue. I reached out to USDA and FDA to ask if that’s what they’re thinking about doing. They said they’re just gathering information at this point. It’s part of a national strategy to reduce food waste.

SHAPIRO: Well, what guidance can you offer those of us today who are unclear about how to interpret these dates on food labels that go by different names?

GODOY: I guess, you know, don’t throw away food just because of the date on the label. There are some foods you have to be more careful about, like deli meats or egg salad or chicken salad. Those don’t stay good for long. But I spoke with Don Schaffner. He’s a food safety expert at Rutgers University. And he says it’s often a judgment call. You know, if it smells bad, don’t eat it.

DON SCHAFFNER: The key message that something doesn’t go from perfectly safe to completely toxic as soon as it passes that date is probably a good bit of advice. And that – again, it probably depends upon the food. It depends upon the individual and how sensitive they are.

GODOY: Now, there are some foods where you have some leeway. He says yogurt, for example, is safe to eat beyond the date on the label as long as you don’t see any mold on it. With hard cheeses, you can cut around the mold and throw that away. But if it’s a moldy soft cheese, toss it. Canned foods – if the can isn’t rusted or bulging, he says it’s probably fine. Now, infant formula is the only food bylaw that requires a date label, and that’s because the nutrient value declines.

SHAPIRO: That’s NPR health correspondent Maria Godoy. Thanks for the info.

GODOY: My pleasure.

Snowboarder’s death in Swiss Alps avalanche is a reminder that even pros face risk

The death of an Olympic snowboarding athlete is a reminder that even the most skilled and experienced athletes are not immune to the threat of avalanches, and that knowledge is key to staying safe.

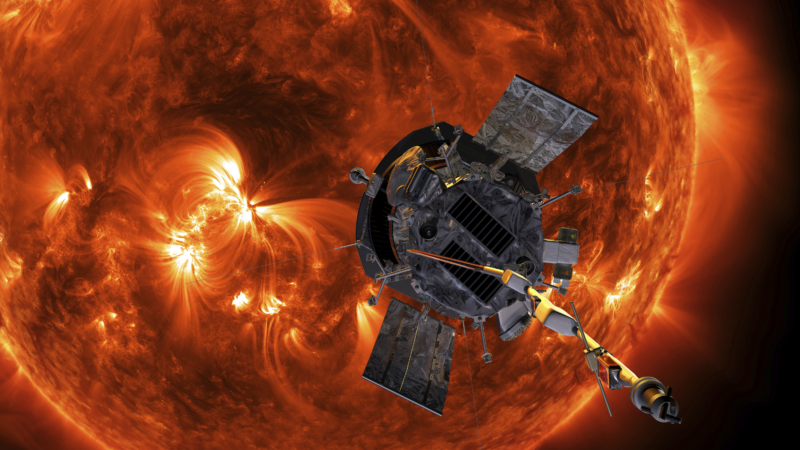

Scientists await signal from spacecraft after historic close encounter with the sun

To get so close, the Parker Solar Probe had to withstand the sun's extreme heat and radiation like no spacecraft before it.

Mega Millions jackpot surges past $1 billion

The Mega Millions prize has now grown to an estimated $1.15 billion, which could be the fifth-largest jackpot in the game's history.

Pope urges ‘all people of all nations’ to silence arms in Christmas address

Pope Francis in his traditional Christmas message urged "all people of all nations" to find courage "to silence the sounds of arms and overcome divisions" plaguing the world, from the Middle East to Ukraine, Africa to Asia.

A gang attack on a Haitian hospital reopening kills 2 reporters and a police officer

Street gangs forced the General Hospital in Port-au-Prince to close earlier this year. As journalists gathered to cover its reopening, suspected gang members opened fire.

Far from the front lines, Ukrainians fight a war to preserve their culture

In the Transcarpathia region, some locals embrace a traditional lifestyle and cultural identity. After surviving Soviet threats, now they fear President Vladimir Putin seeks to erase their culture.