California’s wildfires may also be catastrophic for its insurance market

ALTADENA, Calif. — Kwynn Perry visited her home this weekend for the first time since the Eaton Fire started. It’s just ashes and rubble.

“This is our bedroom,” she says. “That is our bed, my antique bed.” It’s now just a blackened, twisted ruin.

Perry and her family leased the home and always had renter’s insurance to cover the expense of relocation and replacing their possessions. That is, until last year. “We were told nobody was insuring renters up this way. So, we had no choice,” she said. With no insurance, Kwynn, her husband Brian and son Ellison are relying on FEMA and a GoFundMe page.

In recent years, insurance companies have begun using sophisticated computer modeling and artificial intelligence to calculate risk in fire-prone areas. That led several companies to stop writing new policies for homeowners and renters in places like Altadena and Pacific Palisades. Janet Ruiz, with the Insurance Information Institute, says, “They did have to restrict coverage so that when we have catastrophes such as the one in Los Angeles, they can pay claims.”

Along with the destruction of lives and homes, the Los Angeles wildfires will also have a big impact on California’s insurance market. Some estimates put insured losses from the fires at more than $20 billion.

California law requires insurance companies to hold reserves adequate to pay out claims even in a catastrophe such as these fires. For that reason, Dave Jones, a former California Insurance Commissioner, doesn’t expect this event will push any companies into insolvency. Jones, who’s now at UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment, says, “It will be an earnings event for them as they say in the industry which means they won’t make profits this year for sure.

But homeowners will also have to help pay for the fires.

Because insurance companies stopped writing new policies in these areas, many homeowners were forced to purchase coverage from California’s FAIR plan. Often called the insurer of last resort, it’s a plan created by the state and funded by the industry. Jones says so many homes in Pacific Palisades had coverage from FAIR, that it may run out of money. If that happens, the plan will impose a special assessment on home insurance policyholders across the state.

Also, under new regulations recently adopted in California, insurance companies are able to use their computer-modeling risk analysis to set higher rates — something that previously wasn’t allowed. Jones says, “There’s no question that before these wildfires, they…were going to raise rates more. Now, with these wildfires, they’re going to be able to ask for even higher rate increases.”

Those new regulations also require insurance companies to continue to write new policies in fire-prone areas. Last week, California’s Insurance Commissioner issued a moratorium that prevents insurance companies from cancelling or not renewing policies in the affected areas for the next year.

Amy Bach, with the consumer group United Policyholders, worries these catastrophic fires will set back efforts to bring insurance companies back to the market in places like Pacific Palisades and Altadena. “Just psychologically,” she says, “this disaster couldn’t have come at a worse time in terms of insurance executives’ renewed confidence in doing business in the state.”

In Altadena, that’s bad news for Perry Bennett.

He owns the building that was home to The Little Red Hen, a coffee shop that’s now just a slab and ashes. He says, “Getting insurance on the Little Red Hen was very difficult because of what just happened. I think it’s going to be very, very difficult, even if you build back. It’s going be difficult to get insurance or it’s going to be really expensive.”

Bach, the consumer advocate, has another concern—people who may have decided to drop their insurance coverage. “For some people, certainly lower-income people who lived in a home they inherited, they may have just said I’m priced out, I can’t afford…ten thousand dollars a year, fifteen thousand dollars a year,” she says. “Some of those people, we may find had no insurance.”

As the cost of insurance continues to rise, Bach and others worry that more people will be tempted to drop their coverage.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

It’s far too early to say how expensive the fires in Los Angeles will be in terms of homes lost, but some estimates have it at more than $20 billion. Whatever the final number, it will have a huge impact on California’s home insurance market, which was already in crisis. NPR’s Greg Allen reports.

GREG ALLEN, BYLINE: In Altadena, Kwynn Perry visited her home this weekend for the first time since the fire. It’s now just ashes and rubble.

(SOUNDBITE OF DEBRIS RUSTLING)

KWYNN PERRY: This was our bedroom. There’s our bed.

(SOUNDBITE OF DEBRIS RUSTLING)

PERRY: My antique bed.

ALLEN: It’s now a blackened, twisted ruin. Perry and her family leased the home and always had renters’ insurance to cover the expense of relocation and replacing their possessions. That is, until last year.

PERRY: We were told that nobody was insuring renters up this way, so we just had no choice.

ALLEN: With no insurance, her family’s relying on FEMA and a GoFundMe page. In recent years, insurance companies have begun using sophisticated computer modeling and artificial intelligence to calculate risk in fire-prone areas. Janet Ruiz with the Insurance Information Institute says that led several companies to stop writing new policies for homeowners and renters in places like Altadena and Pacific Palisades.

JANET RUIZ: They did have to restrict coverage so that when we have catastrophes such as the one in Los Angeles, they can pay claims.

ALLEN: California law requires insurance companies to hold reserves adequate to pay out claims even in a catastrophe such as these fires. For that reason, Dave Jones, a former California insurance commissioner, says he wouldn’t expect this event will push any companies into insolvency.

DAVE JONES: It will be an earnings event for them, as they say in the industry, which means they won’t make profits this year for sure.

ALLEN: Homeowners will also have to help pay for the fires. Because insurance companies stopped writing new policies in these areas, many homeowners were forced to purchase coverage from California’s FAIR plan. Often called the insurer of last resort, it’s a plan created by the state and funded by the industry. Jones says so many homes in Pacific Palisades had coverage from FAIR that it may run out of money. If that happens, the plan will impose a special assessment on home insurance policyholders statewide. Also, under new regulations recently adopted in California, insurance companies are able to use their computer modeling risk analysis to set higher rates, something that previously wasn’t allowed.

JONES: There’s no question that before these wildfires, they have been and were going to raise rates more. Now with these wildfires, they’re going to be able to ask for even higher rate increases.

ALLEN: Those new regulations also require insurance companies to continue to write new policies in fire-prone areas. Last week, California’s insurance commissioner issued a moratorium that prevents insurance companies from canceling or not renewing policies in the affected areas for the next year. But Amy Bach with United Policyholders, a consumer group, worries these catastrophic fires will set back efforts to bring insurance companies back to the market in places like Pacific Palisades and Altadena.

AMY BACH: You know, just psychologically, this disaster couldn’t have come at a worse time in terms of insurance executives’ renewed confidence in doing business in this state.

ALLEN: In Altadena, that’s bad news for Perry Bennett. He owns the building in Altadena that was home to The Little Red Hen, a coffee shop that now is just a slab and ashes.

PERRY BENNETT: Getting insurance on The Little Red Hen was very difficult because of what just happened. I think it’s going to be very, very difficult. Even if you build back, it’s going to be difficult to get insurance or it’s going to be really expensive.

ALLEN: Bach, the consumer advocate, has another concern – people who may have decided to drop their insurance coverage.

BACH: For some people, you know, certainly, like, lower-income people who are living in a home they inherited, they may have just said, I’m priced out. I can’t afford, you know, $10,000 a year or $15,000 a year or what have you.

ALLEN: As the cost of insurance continues to rise, Bach and others worry that more people will be tempted to drop their coverage.

Greg Allen, NPR News, Los Angeles.

Asian markets plunge with Japan’s Nikkei diving nearly 8% after big Wall St. meltdown

Asian shares nosedived on Monday after the meltdown Friday on Wall Street over U.S. President Donald Trump's tariff hikes and the backlash from Beijing.

UConn takes 12th NCAA women’s basketball title with dominant win over South Carolina

UConn is back on top of women's basketball, winning its 12th NCAA national championship by routing defending champion South Carolina 82-59 on Sunday.

Alex Ovechkin scores goal #895 to break Wayne Gretzky’s all-time NHL scoring record

The Washington Capitals star made history with a power play goal from the left faceoff circle — as Gretzky, who last set the record more than 25 years ago, looked on.

Severe storms and floods batter South and Midwest, as death toll rises to at least 18

Severe storms continued to pound parts of the South and Midwest, as a punishing and slow-moving storm system unleashed life-threatening flash floods and powerful tornadoes from Mississippi to Kentucky.

Israeli strikes on Gaza kill at least 32, mostly women and children

Israeli strikes on Gaza killed at least 32 people, including over a dozen women and children, local health officials said Sunday, as Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu headed to meet President Trump.

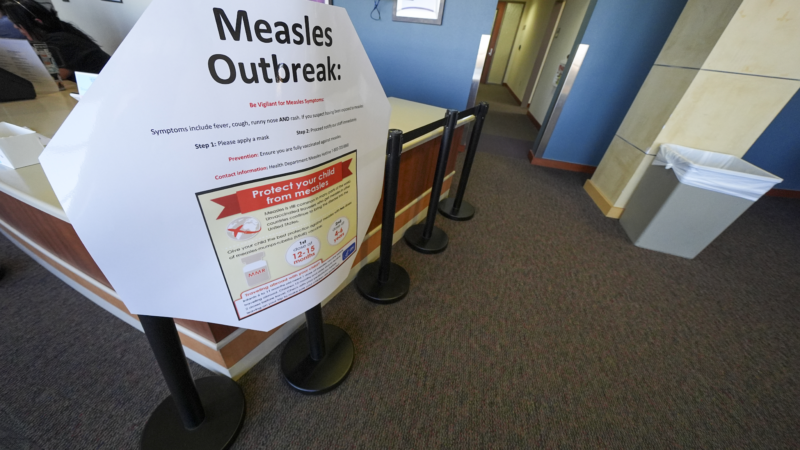

Second child dies from measles-related causes in West Texas, where cases near 500

A second school-aged child in West Texas has died from a measles-related illness, a hospital spokesman confirmed Sunday, as the outbreak continues to swell.