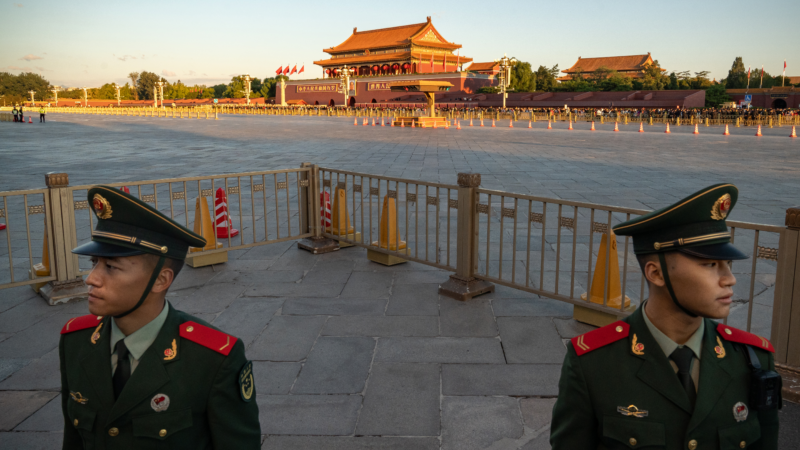

At Tiananmen Square, tight security with metal detectors reflects a changing China

BEIJING — It was my second attempt in as many days to visit Tiananmen Square, and it wasn’t looking good.

When I tried the day before, a guard said I required an online appointment — and, no, I couldn’t make a same-day booking. So, I scanned a QR code, entered my name and passport number, and returned the following day.

Now, I was at the front of a line of dozens of people trying to get onto the world’s biggest public square.

Just making it here was a process: There was a police ID check to exit the nearby subway station. Another to get in line on the sidewalk. A third while standing in line. And now, there was a fourth — by a towering police officer standing before a bank of metal detectors and X-ray machines — the final inspection.

My journalist visa caught his eye. He told me to step aside, and radioed his boss.

Another cop arrived. Foreign reporters, he said apologetically, need special permission. And I did not have it.

Seventy-five years ago last month, Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People’s Republic from atop Tiananmen, the Gate of Heavenly Peace. Situated on the southern edge of the imperial Forbidden City, few symbols of power in China rival it.

The vast square that unfolds at its feet is another symbol of power, which over the decades has vacillated between people — and the state.

A protest tradition took root in Tiananmen Square more than 100 years ago when students marched through the square in 1919 — the May Fourth Movement. They were protesting the terms of the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I.

After the Communist Party took power in 1949, it expanded the square. The party installed two huge buildings on its east and west flanks — and placed a monument to heroes of the revolution in the middle.

“That all happened in the 1950s, basically to prepare for 1959, which was the 10th anniversary,” says Yu Shuishan, an expert on Beijing’s urban architecture at Northeastern University.

And the party had a model in mind. “Basically, copying Moscow,” Yu says.

The square was to be a grand public venue, like the Soviet Union’s Red Square, for parades and mass gatherings.

State power

In the 1960s and ’70s, Mao brought thousands of young Red Guards to Tiananmen Square to sing his praises during the Cultural Revolution.

There have been military parades for milestone anniversaries of the founding of the country, and celebrations for other major events, including the 2021 centenary of the establishment of the Communist Party of China.

Those big shows of state power jostled against other things happening in the square. In 1976, thousands gathered in Tiananmen Square spontaneously to mourn the death of Premier Zhou Enlai.

There were protests there in the 1980s — and in 1989, students took over the square for months — until the army crushed the movement.

Those protests, and the crackdown, broadcast across the world, brought the square more attention — and enhanced its significance and sensitivity.

Security in Tiananmen Square increased. But it was still possible to hang out there. People flew kites in the square. You could bike or skateboard there.

Sporadic demonstrations still occurred in the 1990s and 2000s. Most were small, and ended quickly in a swarm of plainclothes and uniformed police patrolling the square.

I’ve seen petitioners toss leaflets into the air at Tiananmen, and unfurl banners. Rep. Nancy Pelosi even did so in 1991 to memorialize demonstrators killed in 1989.

People have lit themselves on fire in Tiananmen Square in apparent protest.

And in 2013, extremists who the government said were linked to a separatist movement drove an SUV through a crowd, leaving several people dead, in front of Tiananmen Gate.

Security was again ratcheted up. Metal detectors and X-ray machines went in. During the coronavirus pandemic, the authorities added a digital booking system to enter — demanding IDs or passports, and controlling the number of people who go onto the square, ostensibly in the name of public health.

The booking system has remained in place.

“In the past, you could do anything there,” says a 69-year-old man surnamed Liu, who has lived around the corner his whole life. He declined to tell NPR his full name out of concern about speaking frankly to a foreign reporter.

“Now, you absolutely can’t do anything.”

Elizabeth Perry, an expert on Chinese politics and protests at Harvard University, says the intensified security reflects the insecurities of the current leadership.

Chinese President Xi Jinping “is very insecure,” she says.

“Not that the party ever welcomed popular protest, but could certainly live with it. But I think that that sense has now disappeared and that any kind of protest, even if it’s very limited demographically and geographically, is seen as potentially dangerous by the party,” she adds.

Perry says that may relate to the way Xi has ruled — culling rivals with an anti-corruption campaign, consolidating power, abolishing term limits and putting the Communist Party back in the center of everyday life. Security has tightened across the board. At the same time, the economy has been floundering.

“There seems to be a kind of collective doom that the current leadership could be in place for a very long time, and there is no longer any institutionalized mechanism for leadership succession,” she says.

Tourists don’t seem bothered by the extra security at Tiananmen Square, which travelers consider a “must visit” in Beijing.

Xie Bin came from the city of Hangzhou to see the square with her kids, who were decked out in red stickers and little Chinese flags. She says it was a good experience.

“[The authorities] have their own considerations for making these restrictions, and as visitors we just need to respect the decision,” she says on a street nearby.

In September, I tried to visit Tiananmen Square again, hoping the third time’s a charm.

NPR requested permission through the Foreign Ministry, which contacted a government office that manages the square and the area around it. After waiting nearly a week, on a glorious early fall day, the request was granted.

I had been on the square countless times, as a tourist and as a student. In more recent years, I had visited as a journalist when foreign leaders were welcomed to China, or when the square was converted into a giant parking lot for party conclaves or sessions of parliament.

Years ago, it felt like an open, organic part of Beijing. Now, it feels like consecrated ground.

A group of tourists from China’s northeast invited me to join them for a photo, with the famous portrait of Mao in the background.

I obliged, but we didn’t talk. A government official and a police officer accompanied me on my visit to the square. And I had been told that interviews were off limits.

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

China celebrated its National Day this week, marking 75 years since Chairman Mao proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

MAO ZEDONG: (Speaking Mandarin).

INSKEEP: We’re hearing a speech he gave at Tiananmen, the Gate of Heavenly Peace, in Beijing. Mao’s 1949 speech is just one of the pivotal events that took place there. In 1989, soldiers violently removed protesters from Tiananmen Square. China has changed a lot over the years, and Tiananmen Square has reflected that change. NPR’s John Ruwitch tried to visit.

JOHN RUWITCH, BYLINE: Going on to Tiananmen Square used to be pretty easy.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED ANNOUNCER #1: We are now arriving at Tiananmen Dong.

RUWITCH: These days, not so much. I tried this summer.

There was an ID check to get off of the subway, and now there’s an ID check to walk down the sidewalk after coming out of the subway. This one required an appointment at least one day in advance.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED ANNOUNCER #2: (Speaking in Mandarin).

RUWITCH: After two more checks, police turned me away. Foreign reporters, they said, are not allowed on the square without special permission. Tiananmen was built in the 15th century. The square at its feet started gathering modern political significance with student-led protests in 1919. The Communist Party would celebrate those protests and the square…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED MUSICAL GROUP: (Singing in non-English language).

RUWITCH: …Which it expanded into the world’s biggest. Yu Shuishan is a professor at Northeastern University.

YU SHUISHAN: That all happened in the 1950s, basically to prepare for 1959, which is the 10th anniversary.

RUWITCH: The 10th anniversary of Mao’s proclamation. He says the party had a model in mind.

YU: Basically, copying the Moscow.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

RUWITCH: They wanted it to be like Red Square. During the Cultural Revolution, there were mass rallies in Tiananmen Square. And that’s where China holds military parades, including, five years ago, for the 70th anniversary.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Non-English language spoken).

UNIDENTIFIED CROWD: (Chanting in non-English language).

RUWITCH: The protest tradition continued, too, in the late ’70s and ’80s.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER #1: Spread out in front of me is the most amazing sit-in in history.

RUWITCH: This is NPR coverage from the spring of 1989.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER #1: Students have turned this entire square into their own city.

RUWITCH: And then…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER #2: Armored columns of troops smashed their way through barricades and entered Tiananmen Square.

RUWITCH: After the crackdown, security was dialed up. There were occasional demonstrations through the ’90s and early 2000s, but most were small and smothered quickly by police. Then, in 2013, there was another turning point.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER #3: (Speaking Mandarin).

RUWITCH: Extremists, who authorities say were linked to an Islamist separatist movement, drove an SUV through the crowd at the top of the square, leaving several people dead. Metal detectors and X-ray machines went in. Finally, early on in the pandemic, the authorities added the online booking system. On a side street, I meet Mr. Liu. He’s 69 and has lived near the square his whole life. He would only tell me his surname, though, because he was worried about speaking frankly to a foreign journalist.

LIU: (Speaking Mandarin).

RUWITCH: In the past, he says, you could do anything in Tiananmen Square.

LIU: (Speaking Mandarin).

RUWITCH: Today, you can’t. Elizabeth Perry is a professor at Harvard University. She says the tight security reflects the insecurities of Chinese leader Xi Jinping, who has purged rivals and presided over a weak economy.

ELIZABETH PERRY: Not that the party ever welcomed popular protest, but could certainly live with it. But I think that that sense has now disappeared.

RUWITCH: I was still interested in going onto the square, so I asked the government for permission. About a week later, my request was granted.

We finally made it to Tiananmen Square. We’re standing in front of the Mao picture on the north end of the square.

UNIDENTIFIED TOURIST: (Non-English language spoken).

RUWITCH: I posed for a snapshot with some tourists.

UNIDENTIFIED TOURIST: (Non-English language spoken).

RUWITCH: But we didn’t talk. I was accompanied by a government minder and a police officer, and I’d been told that interviews were off limits.

John Ruwitch, NPR News, Beijing.

(SOUNDBITE OF DRXNK’S “BY THE SEA”)

Party City files for bankruptcy and plans to shutter nationwide

Party City was once unmatched in its vast selection of affordable celebration goods. But over the years, competition stacked up at Walmart, Target, Spirit Halloween, and especially Amazon.

Sudan’s biggest refugee camp was already struck with famine. Now it’s being shelled

The siege, blamed on the Rapid Support Forces, has sparked a new humanitarian catastrophe and marks an alarming turning point in the Darfur region, already overrun by violence.

FDA approves weight loss drug Zepbound to treat obstructive sleep apnea

The FDA said studies have shown that by aiding weight loss, Zepbound improves sleep apnea symptoms in some patients.

Netflix is dreaming of a glitch-free Christmas with 2 major NFL games set

It comes weeks after Netflix's attempt to broadcast live boxing between Jake Paul and Mike Tyson was rife with technical glitches.

Opinion: The Pope wants priests to lighten up

A reflection on the comedy stylings of Pope Francis, who is telling priests to lighten up and not be so dour.

The FDA restricts a psychoactive mushroom used in some edibles

The Food and Drug Administration has told food manufacturers the psychoactive mushroom Amanita muscaria isn't authorized for food, including edibles, because it doesn't meet safety standards.