Another casualty of Israel’s war in Lebanon: Efforts to save endangered turtles

MANSOURI BEACH, Lebanon — Just a few months ago on this deserted Mediterranean beach, Fadia Joumaa and a small group of volunteers were working to help newly hatched endangered sea turtles make their way to the sea.

The beach is a few miles from the Lebanese-Israeli border, however, and after Israel escalated airstrikes in Lebanon in late September, what had been merely risky became impossible.

“The area is currently under heavy bombardment,” said Joumaa, who like hundreds of thousands of others in Lebanon has now been displaced. “It’s not possible to reach the beach or anywhere near it,” she said from the Lebanese city of Sidon.

Despite a ceasefire reached in November in the war between Israel and the militant Lebanese group Hezbollah, by January, Joumaa said the town of Mansouri and the nearby beach where turtles nest was still off-limits to civilians. Israel and Hezbollah must withdraw from southern Lebanon by Sunday, but without that withdrawal, security is still unsettled.

In mid-September, as the green sea turtles began hatching, Joumaa and the other volunteers dug down into the sand until their shovels hit metal grates they had placed over nests in the sand.

The grate was to keep away dogs and an increasing number of foxes that come down to the beach at night and dig up the eggs. The foxes are a legacy of the 2006 war between Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia and Israel, when the animals moved down to the coast to escape fighting in the hills.

This part of southern Lebanon has been the focus of cross-border fighting between Hezbollah, the most powerful armed group in Lebanon, and Israel.

The war has had a huge human cost, with more than 4,000 Lebanese killed in Israeli airstrikes, according to Lebanon’s health ministry. About 76 people have been killed in Hezbollah attacks in northern Israel.

But it has also taken its toll on the environment and efforts to help green sea turtles, a species little changed over 100 million years but now on the brink of extinction.

“Now during the war it’s become more difficult for us. We can’t come to the beach at night,” because of fears of Israeli airstrikes, said Joumaa, 46.

Nighttime is when female turtles come in from the sea to lay their eggs, returning to the water as soon as they cover them with sand. It is also when dogs and foxes come down to dig up the nests. The night before, Joumaa said, dogs unearthed 10 nests and ate hundreds of sea turtle eggs.

The danger of airstrikes in the area and Lebanon’s severe financial crisis drastically reduced the number of core volunteers to just four or five on most days, compared to more than a dozen before the coronavirus pandemic and the latest conflict with Israel.

But Joumaa and her team have still managed to help thousands of newly hatched turtles evade predators to make their way to the sea. The odds of their survival to adulthood though are extremely slim — about 1 in 1,000.

“If we can save one or two every season that’s very good,” Joumaa said. “We are trying to preserve the balance of nature. There is nothing in the sea that can compensate for the turtles’ absence.”

Green sea turtles are herbivores — their diet of seagrass and seaweed prevents coral reefs from being overgrown by the aquatic plants. The more populous yet still threatened loggerhead turtles feed on shrimp and shellfish, as well as jellyfish, and also maintain the balance of marine life.

The lifespan of the newly hatched turtles the volunteers placed in a bucket to release to the sea mirrors that of humans; it takes more than 20 years to reach maturity and some live up to 100 years old.

While male sea turtles never leave the water once they’ve reached it, females that survive to adulthood travel hundreds and even thousands of miles to lay eggs on the same beach where they were born.

Once they lay the eggs and cover them with sand, they return to the water, leaving the eggs vulnerable to predators. Around the world, development that has destroyed their nesting grounds and fishing nets that accidently trap and drown the turtles have brought them to the brink of extinction. Some species of sea turtles die after ingesting plastic bags they mistake for jellyfish, another food source.

Joumaa’s team took out the eggs that were ready to hatch to be able to protect them as they made their way to the water.

The hatching green sea turtles wriggled out of soft leathery eggs the size of ping-pong balls, frantic to get to the sea. In the few feet from the nests to the water’s edge there are multiple dangers — in addition to dogs and foxes there are crabs and seabirds that eat the baby turtles. Even footprints in the sand can pose a danger to the tiny creatures, which can fall into them without being able to get up again.

Of the 61 turtle nests they found this season, only five were green sea turtles. The rest were loggerhead turtles, classified as threatened with extinction.

An important part of the job is involving the community in preservation efforts. On their mission in September, with dusk approaching, Joumaa said a small group on a deserted part of the beach at sunset could be mistaken for fighters and it was too dangerous to stay where they were.

She picked up a large Lebanese flag that waved in the breeze as they walked to the safer public beach to release the last green sea turtles of the season.

One of the residents of the town of Mansouri, Haji Rabie al-Masri, had come down to the beach with his son and his brother and sister to see the turtles.

“Everyone has to help protect the environment,” he said. “God willing, things will calm down and tourists will come back to see this.”

There is little government support for their work, but Joumaa has tried to involve local residents in the conservation efforts.

Making her way past gardenia and bright pink bougainvillea bushes growing wild near the beach, Joumaa pointed out bags of trash her team picked up after the mostly plastic waste washed ashore on the beach.

“There are no trash cans here,” said Joumaa. “And there are no signs to tell people about the beach and the turtles.” Lebanon is experiencing a long-running economic and financial crisis and a political deadlock that has left it without a fully functioning government for almost two years.

Joumaa said the Tyre municipality, where Mansouri Beach is located, has provided a small amount of money, but that grant runs out next year.

An Italian organization, Blue Tyre, had stepped in to pay some expenses, such as fuel and basic equipment. Joumaa has been to Italy twice for training but said her volunteer group is still learning as they go along.

“We are not experts. We are learning from our mistakes,” said Joumaa, who works as a journalist for a Lebanese online news outlet and in conflict resolution. “We don’t know where all the nests are.”

She checked the temperature of the sand during the incubation period for research purposes — sending data to Italy. Sometimes they find tracks of female turtles on the sand but no eggs laid.

“Something has bothered them — we don’t know what it is,” she said.

Joumaa said if there were more volunteers, they could protect more of the nests, but not everyone was willing to risk the threat of Israeli airstrikes, or could afford to take time off work.

The day before, two civilians in their 20s were killed in an Israeli airstrike in the area, according to UNIFIL, the United Nations peacekeeping mission. It was in the daytime, just a few miles ahead of where Joumaa was driving.

To avoid being seen as a threat, she avoids using her four-wheel-drive vehicle, which is more likely to be targeted by airstrikes than the small car she uses instead.

She and other longtime volunteers said they learned most of what they know from Lebanese conservationist Mona Khalil, a pioneer here in environmental preservation. Khalil stopped her efforts after more than two decades and has largely withdrawn from public life.

“We are all children of Mona,” said Joumaa, who resumed the turtle rescue herself last year, two years after Khalil retired.

“I started when I was very young to work on this beach and it’s all because of Mona,” said Miriam Bazzi, Joumaa’s daughter, who is in her 20s. “I found my joy here.”

She and the other volunteers took the baby turtles from the bucket, their tiny flippers already frantically spinning even before they set them down on the sand.

They scurried toward the water, some of them turning over before righting themselves and others knocked back by the waves only to try again once the water receded.

The newly hatched turtles will have to swim more than a mile to reach the sea grass that they feed on and dodge being eaten by fish, crabs and seabirds. Many of the air-breathing reptiles drown in fishing nets that do not allow creatures inadvertently caught to escape.

“At first I was very upset and sad about this,” Joumaa said about the turtles’ low survival rates. “But when I worked more on this, I began to understand that this is the cycle of life. There are other creatures that need to eat to live. God created a balance.”

Jawad Rizkallah contributed reporting from Mansouri, Lebanon.

Transcript:

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

Endangered sea turtles are hatching on the coast of Lebanon and making their way to the Mediterranean. The turtles have essentially remained unchanged for a hundred million years. Their habitat has not. Coastal development, fishing nets and plastic trash have brought them to the edge of extinction. NPR’s Jane Arraf has the story of a group of volunteers who are braving the fighting near Lebanon’s border and trying to give the turtles a chance at survival.

(SOUNDBITE OF SHOVELING)

JANE ARRAF, BYLINE: Fadia Joumaa and her team are digging into the sand. They stop before they reach the pingpong-ball-sized eggs buried about 3 feet down. Left to themselves, these endangered green sea turtles would hatch and make their way at nightfall down to the water. But night is when the foxes and dogs come down and eat any eggs they find. The volunteers carefully place the newly hatched turtles on the sand.

FADIA JOUMAA: Yes.

ARRAF: He’s hatching.

JOUMAA: Yes.

ARRAF: He’s actually coming out of his little shell, and you can see him struggling his tiny, little flippers. And he’s halfway out now. These little creatures have less than 1 in 1,000 chance of growing to adulthood. But gosh, they’re determined.

JOUMAA: Yeah.

ARRAF: Sea turtles have roughly the same lifespan as humans. They mature at about 20 years old and can live up to 100 years. But on this first day of their lives, there are many dangers.

JOUMAA: (Through interpreter) Of course, the fish eat them. The birds wait for them on the water’s surface. After they reach the water, we can’t do anything for them.

ARRAF: Adult females will travel back hundreds of miles to lay eggs on the same beach where they were born.

JOUMAA: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: When we come back to the same beach the next day, the team removes iron grates they’ve put on nests to keep out predators. Joumaa’s daughter, Miriam Bazzi, places the turtles in a bucket to release. I ask her why she does this.

MIRIAM BAZZI: I found my joy ’cause we’re protecting such a beautiful creature.

ARRAF: A beautiful creature. It’s true.

There are far fewer volunteers this year because of fighting along the Lebanese-Israeli border, just a few miles away, that’s been raging since the start of the Gaza war. The day before, an airstrike not far away killed two young Lebanese civilians, according to U.N. peacekeepers.

JOUMAA: (Through interpreter) If we had more volunteers, it would be much better. But today, we are in a war, and not everyone is OK with the danger. In previous years, it might have been OK, but now we are also living in very difficult economic conditions.

ARRAF: Joumaa says along with funding, they need more training. She’s been to courses in Italy but learned most of what she knows from Mona Khalil, a Lebanese conservationist who protected the turtles for decades. Now in her ’70s, she no longer does.

As the sun sets, Joumaa says they could be a target on this deserted beach. They head down to the public beach, where families have come to watch.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: And then the volunteers take the turtles out of the bucket one by one and set them down. Even before they reach the ground, their tiny flippers are flapping like windmills.

Oh, my gosh. It’s like watching a race. Some of them are on their backs. Oh, one of them’s rolling down the sand dune. And then the ones who have actually gotten there, the big waves are coming in, and they’re taking them away.

(SOUNDBITE OF WAVES)

ARRAF: They’ll have to swim out more than a mile to get to the seagrass they eat. A lot of them are accidentally caught in fishing nets and drown. Other sea turtle species die when they eat plastic bags, which they mistake for jellyfish. Joumaa’s small team has released about 2,000 sea turtles this season. I asked her why with such slim odds of surviving – 1 in 1,000 – she works so hard at it.

JOUMAA: (Speaking Arabic).

ARRAF: “I used to be very sad about this,” she says. “But then I understood this is the cycle of life. God created a balance.”

(SOUNDBITE OF WAVE CRASHING)

ARRAF: “If we can save one or two of these unique creatures every year,” she says, “it’s worth it.” Jane Arraf on Mansouri Beach, Lebanon.

Grilled by Senate, Boeing CEO admits to “serious missteps” on safety

Boeing's CEO admits the company "made serious missteps" that hurt the safety of its planes. But denies the company pressures workers to speed up airplane production.

White House reviewing TikTok proposal to lease algorithm from China

President Trump and top officials are considering a deal that would create a new U.S. entity and lease TikTok's algorithm to get around China export regulations.

Parents sue Bucknell alleging hazing led to freshman football player’s death

Freshman Calvin "CJ" Dickey Jr., died after his first practice at the university. His parents are suing the school, also alleging staff neglected to account for his sickle cell trait during training.

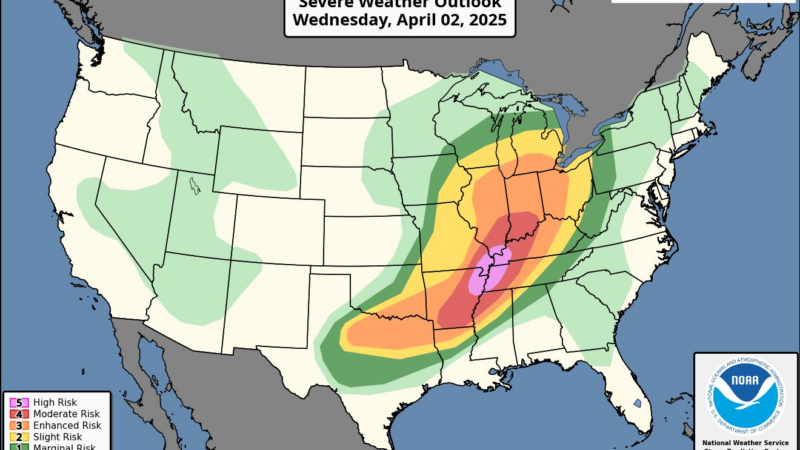

Central U.S. braces for tornadoes and flash flooding as powerful storm approaches

The National Weather Service says a "multi-day catastrophic and potentially historic" storm is expected to impact multiple states beginning on Wednesday.

Supreme Court hears case that could see more Planned Parenthood clinics closed

The Supreme Court heard arguments on whether South Carolina can remove Planned Parenthood clinics from its state Medicaid program, even though those funds cannot generally be used to fund abortions.

Sen. Cory Booker on his marathon, 25-hour speech on the Senate floor

Sen. Cory Booker, a Democrat from New Jersey, told NPR's Juana Summers he stopped eating and drinking before his record-breaking speech.