Ann Patchett finds bits of Catholicism and America appalling: ‘But I am those things’

A note from Wild Card host Rachel Martin: Ann Patchett is a hugely popular writer. She was a Pulitzer finalist for her book The Dutch House. Her most recent novel, Tom Lake, was a New York Times bestseller. But she’s perhaps most well known for her 2001 book Bel Canto.

It tells the story of a group of strangers taken hostage somewhere in Latin America. It’s lyrical and heartbreaking and it has been adapted into an opera and a movie. Overall, it’s been a massively successful book. And Patchett recently decided to do a fascinating thing: She published an annotated version of Bel Canto with her own handwritten notes in the margins.

She calls out clunky turns of phrase, confusing plot points, repetitive language. She also gives herself credit for good writing and thoughtful observations about the human condition. But mainly, she is owning her shortcomings. Which feels like a bold quality that we need more of.

This Wild Card interview has been edited for length and clarity. Host Rachel Martin asks guests randomly-selected questions from a deck of cards. Tap play above to listen to the full podcast, or read an excerpt below.

Question 1: What’s a place that shaped you as much as any person did?

Ann Patchett: When I was a child, we lived on a farm for several years. It was in Ashland City, about 30 minutes outside of Nashville. It was not a working farm. It was just a collection of absolute weirdness.

We had a couple of horses. We had a rabbit. We had chickens, which were all named after members of Nixon’s cabinet. We had dogs, which meant that dogs would just go through and they would stay for a couple of years. Same with the cats. It was real country life. And most importantly, I had a pig, which I got from my ninth birthday because I was obsessed with Charlotte’s Web.

It was just a very animal-laden, isolated life. And because I’m an introvert, that worked out fine for me. And childhood was: you would go outside and climb up a hill. I collected moss, lots of flowers. I actually had a moss business. I sold moss in town when I was about 10 to florists.

Rachel Martin: Wait, other kids are like selling lemonade and little Ann Patchett is like, “Some moss, sir?”

Patchett: I’m in the moss trade. Make a lot more money off a moss than you do lemonade, Rachel.

And I remember my mother saying things like, “Remember the rattlesnakes are blind when they’re molting. So if you get into the blackberry bushes where the rattlesnakes go to shed their skins because they have those little tiny thorns on the blackberry bushes, just be aware because they can’t see you so they’re more likely to strike.”

That was the bedrock advice of my childhood.

Question 2: What’s an expression of love you’re trying to get better at?

Patchett: Complete acceptance. Complete blanket acceptance, which is the love my husband gives to me. He just accepts me for who I am. Always. No matter what. And I think I’ve always been somebody who wants to fix, and I work very hard to not fix and to just see the people in my life and accept them for who they are and love them for who they are.

Martin: Is this right — that you dedicated the original version of Bel Canto to the man who is now your husband and you weren’t married, you were just dating?

Patchett: Yes. Yes! What kind of madness was that? And I want to tell you – my second novel, which was a book no one ever read called Taft – I dedicated it to my boyfriend at the time. And I found out that he was, shall we say, stepping out on me as the book was going to press. And I frantically called my publisher and said, “Can you pull this?” And they were like, “Hang on, let me check. Yes! We got it back!”

Martin: It’s like you stopped the tattoo artist right as they were about to go into your arm to put his name.

Patchett: It’s so true. And I dedicated it to my beloved cousins. And I thought, “Never gonna make that mistake again.” But then I met the right guy and I dedicated the book to him. And we weren’t married because I didn’t want to get married, but I knew that I would always be with him.

Question 3: How have your feelings about God changed over time?

Patchett: So there’s a lot about God in Bel Canto. There’s a lot about faith. And one of the things that I found very moving when I went back to it was I was much closer to my Catholic faith when I was 35 or 34, when I was writing that book.

You know, it’s a two-part thing. There’s God and then there’s Catholicism, which I always say, Catholicism is to God what sorority is to college. For some people, it’s everything. For some people, it’s nothing. For other people, it’s part of the experience.

I still believe in God. And here’s the thing, if I tried to tell you what that meant, I would be wrong. The only thing that I know for sure is that whatever I know is wrong. And it does not behoove me to spend a moment’s time thinking about it.

We are alive and that’s an astonishing gift. And it seems very possible to me that being alive is God and that the trick is whether or not we know it. The trick is whether or not we can keep our focus and remember that we are, for all of the suffering, the recipient of the most beautiful gift for a limited period of time, which is our life.

Martin: I’m interested in your preservation of the word “God” to define that. That the word carries so much for me because of how I was raised. And so it feels very dramatic for me to say, “I don’t believe in God.” But I guess I appreciate that you, even though you are no longer a Catholic and don’t identify that way —

Patchett: Yes I do. I don’t go to church, but I do still call myself a Catholic.

Martin: But that’s even more interesting!

Patchett: I am still a Catholic and there is an enormous amount about Catholicism that I don’t believe and am appalled by. I am still an American and there is an enormous amount about being an American that I don’t believe in and that I am appalled by. I am a Tennessean. There is an enormous amount about being a Tennessean that I don’t believe in and I am appalled by. But I am those things. And there are – about all of those things – parts that I love and I’m proud of.

When I was a sophomore at Sarah Lawrence, I had a humanism teacher. We had a class called “Humanism.” And it was a point in my life where I thought, “I loathe Catholicism. I want nothing to do with this. This is just an anathema to everything of who I am and who I believe in, what I believe in.”

And I went out to dinner at the Raceway Diner, I remember, in Yonkers with my humanism teacher. And I told him my problems. And he said, “If you’re going looking for something as big as God, just go where you’re comfortable. Go with what you know. It doesn’t make any difference. You’re not going to pick a better religion. You’re not going to pick a better set of words. It’s not about the words. It’s not about the religion. Don’t waste your time picking out your luggage. Just go on the trip.”

What matters is that we do our best with the life that we have, that we show up, that we love each other, and that we try to be as aware as is humanly possible of the life and the gift that we’re given, and to help other people wherever we can.

The Assad regime’s fall has freed displaced Syrians stuck in a remote desert camp

More than 7,000 people had taken shelter in the Rukban camp, near the border with Jordan, many of whom fled the regime and ISIS attacks almost a decade ago.

Mariah Carey and K-pop group Stray Kids rule this week’s charts

Holiday music rules the pop charts once again this week, as Mariah Carey's "All I Want for Christmas Is You" scores its 17th nonconsecutive week at No. 1 — the third longest run of all time.

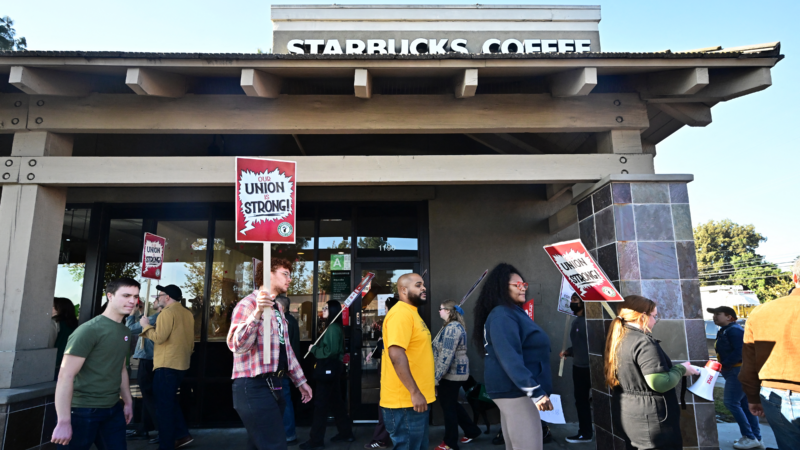

Starbucks baristas’ ‘strike before Christmas’ has reached hundreds of U.S. stores

Starbucks' union says workers are walking off the job at some 300 — out of over 10,000 — stores across the U.S. as contract negotiations falter. The company urges it to return to the bargaining table.

American Airlines lifts ground stop that froze Christmas Eve travelers

American Airlines passengers across the U.S. endured a sudden disruption of service on Christmas Eve as a "technical issue" forced the airline to request a nationwide ground stop of its operations.

We needed comic relief in 2024. Here are 5 stand-up specials where we found it

Hasan Minhaj, Ronny Chieng, Mike Birbiglia, Hannah Einbinder and Michelle Buteau all delivered specials that cracked us up this year.

An Indian movie, loved abroad, is snubbed at home for Oscar submission

All We Imagine as Light explores the lives of working-class women in Mumbai and won the Grand Prix at Cannes. But it was deemed not Indian enough to submit to the Oscars.