A warden faced discipline over abuse at a prison. Now he runs a prison training site

)

A warden who oversaw a culture of abuse at two different federal prisons has a new job — running a national training academy for the Bureau of Prisons.

Andrew Ciolli was in charge of the penitentiary at Thomson in Illinois for one year before he moved to lead an even larger and more high-profile prison complex in Florence, Colo. An internal investigation by the Bureau of Prisons conducted last spring found that some staff at Florence used excessive force in violation of policy, and Ciolli, as warden, should have stopped it — but didn’t. Investigators referred him for disciplinary action. But he’s now landed a role as the director of the bureau’s Management and Specialty Training Center, which provides leadership training and specialized instruction across the agency.

“Historically, when a warden is disciplined for misconduct, they aren’t reassigned as a director of anything, let alone a training center,” said Thomas Bergami, who succeeded Ciolli as warden at Thomson before retiring last year.

Reporters reached out to Ciolli at a bureau email address for his new position. An unsigned response to that email declined to comment and referred reporters to the bureau’s Office of Public Affairs.

In a statement, Bureau of Prisons spokesperson Carl Bailey confirmed that Ciolli oversees the day-to-day operations at the training center, but said he “does not provide or oversee training.” Responsibility for the training “rests exclusively with subject matter experts, who operate independently of Mr. Ciolli’s oversight,” Bailey wrote.

He added that “allegations of employee misconduct are taken seriously,” and that the bureau “fully cooperates” with watchdog agencies “to bring to justice those who abuse the public trust.”

After a two-decade career rising through the ranks at the Bureau of Prisons, Ciolli became warden at Thomson in February 2021. An investigation by NPR and The Marshall Project exposed how during his tenure, three people were killed and dozens more alleged in lawsuits and interviews that they suffered serious mistreatment. Many incarcerated people described being shackled for hours or days at a time without access to food or a bathroom. The restraints were so tight, they often left scars on people’s wrists, stomachs and ankles that prisoners nicknamed the “Thomson tattoo.”

According to Bureau of Prisons policy, restraints should only be used on someone who is in immediate danger of hurting themselves or others or causing serious property damage. While staff can temporarily apply restraints, a warden must approve their continued use.

When Bergami took over the facility from Ciolli in 2022, he discovered an “enormous problem with inmate abuse,” he said in an interview last year. The Bureau of Prisons shut down a high-security unit at Thomson in 2023, citing “significant concerns with respect to institutional culture and compliance with BOP policies.”

In 2023, bureau Director Colette Peters testified before Congress that multiple Thomson staffers had been referred for administrative and criminal investigation for their roles in abusing prisoners. She did not name the employees. The bureau declined to comment on the status of those investigations.

After Ciolli left Thomson in 2022, Bureau of Prisons officials reassigned him to run the even bigger complex in Florence, with a $20,000 raise, according to the bureau. The job included overseeing a medium-security prison, a high-security penitentiary and the Supermax — which houses some of the country’s most notorious prisoners in single-cell solitary confinement.

A staffer at Florence becomes a whistleblower

But the recent federal investigation revealed that similar patterns of mistreatment found at Thomson, such as the excessive use of restraints, followed Ciolli to Florence. Last spring, a staffer at Florence who was tasked with investigating employee misconduct reported that officers were routinely using restraints on prisoners who did not meet the criteria for such treatment, according to a letter he wrote to federal officials. “All inmates were behind a secure door, no immediate threat to staff existed, and no actual disruptive behavior was observed from any inmate that would have placed a staff member in danger,” the whistleblower wrote to the U.S. Office of Special Counsel, an independent agency that handles such complaints.

The names of Ciolli and other Florence officials are redacted in investigative records obtained by NPR and The Marshall Project. But their job titles and descriptions are included, and two people with knowledge of the investigation confirmed their identities.

Investigators with the Bureau of Prisons’ Office of Internal Affairs reviewed video footage collected over nearly nine months at Florence penitentiary and found multiple instances of employees using force against prisoners who were “compliant, under control, and not a threat to staff or others,” according to a letter from the Office of Special Counsel to President Joe Biden.

Michael Antonio Thompson said he was restrained three times during the roughly 18 months he spent at Florence penitentiary, much of it while Ciolli was warden. Thompson was once left in cuffs for over 10 hours, he said. Officers “used to pepper spray me for nothing, hold me in chains for a whole bunch of hours,” he said in a phone interview. “Some people will put you in chains and put the handcuffs real tight until your hands turn blue and they swell up like baseball gloves.” He was released from prison in 2023.

Bailey, the bureau spokesperson, declined to comment on Thompson’s experience, for “privacy, safety and security reasons.”

The Bureau of Prisons’ internal investigation found the overuse of restraints at Florence was part of a broader program known as the High Visibility Watch Program, records from the whistleblower investigation show. The program targeted prisoners who were accused of masturbating in front of officers. Guards were instructed to fire pepper spray into their cells, force them into restraints and escort them to solitary confinement — whether or not they posed an immediate threat, investigators found. Those prisoners were then labeled with a yellow card around their neck.

These measures posed a “significant threat” to those in the program, the whistleblower wrote, “as inmates who engage in masturbation in a prison setting are prone to extortion, rape or assault from fellow inmates.” The Office of Internal Affairs found the program violated bureau policy, the office’s records show.

Several other employees moved from Thomson to Florence around the time of Ciolli’s departure in 2022, including Associate Warden David Altizer. According to the investigation by the bureau’s Office of Internal Affairs, staff members reported that Altizer and Ciolli called officers into a meeting after they arrived at Florence and instructed them to implement the watch program. The whistleblower told investigators that Altizer and Ciolli said “they had conducted a similar program at another location, and it was successful.”

When asked by investigators, Ciolli denied involvement and said he “could not remember” telling staff about the program, according to the bureau’s Office of Internal Affairs. Altizer was not interviewed in the inquiry, because he went on long-term medical leave shortly after the investigation began, according to documents from the investigation. Investigators concluded that at the very least, Ciolli was “responsible for providing managerial oversight and was accountable for determining policy” of the complex.

Altizer did not reply to requests for comment.

The whistleblower wrote in a separate letter to the Office of Special Counsel that a third official at the complex was involved in implementing the program. That person was cleared by the investigation and not referred for disciplinary action, and instead was promoted to warden of another prison complex.

This investigation was referred to several federal agencies, ultimately resulting in a report from the Office of Special Counsel to Biden explaining that most of the whistleblower’s allegations were true.

Both Altizer and Ciolli were referred for discipline, but neither was fired from the agency. Altizer retired in April. Ciolli began his new position with the training center in July, according to his LinkedIn profile and an internal bureau announcement. He lost his status as a senior executive in the agency and took a $3,350 pay cut, according to an email from the Bureau of Prisons.

After a string of scandals in the bureau, Congress has moved to increase oversight of the agency. This summer, Biden signed a law that would create a new ombudsman position in the Justice Department and require regular inspections of facilities with higher risk of mistreatment.

After the whistleblower report from Florence, the bureau also updated its use-of-force policy for the first time in a decade. It now explicitly states zero tolerance for excessive force, and that misconduct could result in criminal prosecution. It mandates de-escalation training and states that employees have an “affirmative duty to intervene” if they witness colleagues applying excessive force.

The policy now makes plain: Restraints may not be used for punishment, or “in any manner which restricts blood circulation” or “causes unnecessary physical pain or extreme discomfort.”

Christie Thompson and Beth Schwartzapfel report for The Marshall Project.

Transcript:

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

Last year, the Federal Bureau of Prisons shut down a troubled unit at the prison at Thomson, Illinois. This came after reporting by NPR’s investigations team and The Marshall Project exposed abuse of prisoners there. Now the man who was the warden has what sounds like an important new job. We’re going to catch up with the latest of all of this. A warning before we get into the conversation – the story does contain a description of sexual activity.

NPR investigative correspondent Joseph Shapiro has been covering this and joins us now. Hey, there.

JOSEPH SHAPIRO, BYLINE: Hey, Scott.

DETROW: Tell us about this latest development.

SHAPIRO: So our new reporting is on Andrew Ciolli. He was the warden at Thomson at the time of some of the worst abuse. And we reported there were several violent deaths at the prison, when prisoners were forced into cells and recreation areas with other men that they knew they’d be forced to fight. We wrote about the overuse of restraints – cuffs and chains that were put on so tight and for so long that they left marks on a prisoner’s ankles and wrists, and men called these their Thomson tattoos.

Now after a whistleblower’s complaint, Warden Ciolli has a new job. In July, he took over as director of the federal center that does specialized and continued training of staff who run the prisons. The Bureau of Prisons told us he runs the day-to-day operation of the training center but that he does not, quote, “provide or oversee the training itself.”

DETROW: OK. Not providing or overseeing the training itself – but still, it does sound like somebody who was in charge of a prison when there was bad abuse still has a job of some significance.

SHAPIRO: That’s right, but it’s not as big a job as the one he got right after he left Thomson. He was sent to run the entire prison complex at Florence, Colorado, and that’s an important job in the Bureau of Prisons.

Now, I did some new reporting with Christie Thompson and Beth Schwartzapfel at The Marshall Project. Our new reporting is based on the revelations of a whistleblower. He’s described in documents as a prison officer, a special investigative agent, working with Ciolli at that prison complex in Florence, Colorado. He alleged that the warden, when he moved to the new prison, brought some of the same abusive practices.

DETROW: Which would be a situation of abuse from one prison spreading to another.

SHAPIRO: Exactly. So again, prisoners were being placed in tight restraints for long periods of time in ways that violated the rules of the Bureau of Prisons. The whistleblower said this happened especially when men were caught masturbating. Sometimes prisoners do that in the open, in front of staff, especially women, and that’s punished as sexual harassment. But we talked to prisoners and the prison staff at the two prisons who say men who were acting privately in their cells – they were getting in trouble.

At Florence, they were pepper sprayed, put in restraints, and that wasn’t the end of it. These prisoners were then required to wear a special khaki jumpsuit and a large yellow tag around their neck that identified them as someone who committed a sexual offense. That yellow card not only shamed these men. The whistleblower said it made them targets, at risk for being attacked by other prisoners and for being extorted for sex or money.

DETROW: What happened after the whistleblower reported all of this?

SHAPIRO: Yeah. Well, we relied upon documents from the U.S. Office of Special Counsel. That’s a federal agency that investigates whistleblower allegations from federal workers. The warden, Andrew Ciolli, told investigators he was unaware of the extent of the abuse, but the whistleblower said he was the one who gave the orders to start the program.

So the Office of Special Counsel found that Warden Ciolli was responsible for problems at the prison. The Bureau of Prisons ended the program that targeted prisoners and said the warden faced discipline. Still, he got that new job…

DETROW: Yeah.

SHAPIRO: …As director of the center that trains others how to run a prison.

DETROW: That is NPR investigative correspondent Joseph Shapiro. Thanks so much.

SHAPIRO: You’re welcome.

(SOUNDBITE OF MAHALIA SONG, “LETTER TO UR EX”)

Fake videos from Russian propagandists aim to raise tensions ahead of Election Day

Intelligence officials says the video, which purported to show a Haitian immigrant claiming he had voted multiple times in Georgie, is the product of a Russian propaganda operation.

Supreme Court sides with Democrats in Pennsylvania voting case

It is hard to estimate how many ballots will be affected by the decision or whether it will ultimately impact the outcome of the presidential election.

What’s Making Us Happy: A guide to your weekend raking, listening and gaming

Each week, guests and hosts on NPR's Pop Culture Happy Hour share what's bringing them joy. This week: The Cure's Songs of a Lost World, a lawn mowing simulator video game, and fall yard work.

Pushed by public opinion shift, Democrats adopt immigration restrictions

President Biden has issued a number of immigration-related executive actions that mimic those of the Trump administration, and VP Harris has promised she’ll continue restrictive policies.

An ‘unprecedented’ good news story about a potentially deadly viral outbreak

The death rate for Marburg virus is nearly 90%. There are no approved vaccines and treatments. So how did Rwanda achieve what one doctor calls an "unprecedented" success in controlling its outbreak?

Employers added only 12,000 jobs in October. That seems bad — but there’s a catch

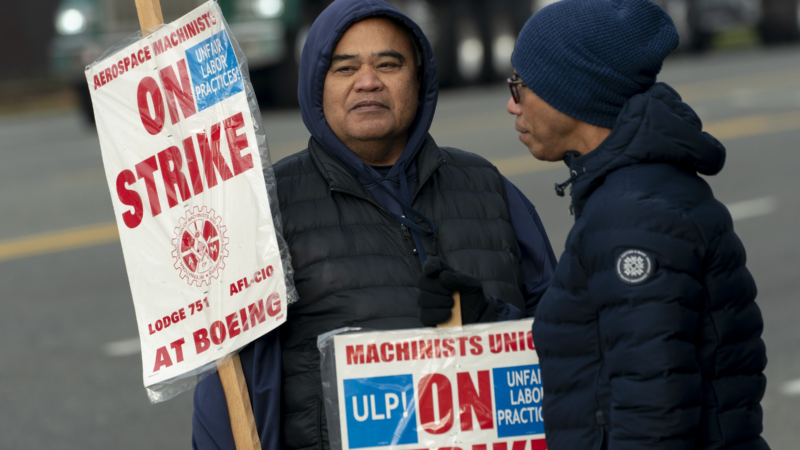

U.S. employers added just 12,000 jobs last month — but the number was depressed by a machinists' strike at Boeing and Hurricanes Helene and Milton.