UAB And JeffCo Officials Plan Hospital-Based Intervention Program For Gunshot Survivors

When a patient arrives at UAB Hospital’s trauma bay with a gunshot wound, doctors and nurses descend upon the scene like a well-trained NASCAR pit crew. Every second counts during the race against the clock to evaluate, stabilize and resuscitate the injured.

“It looks like chaos, but it’s organized chaos,” said Dr. Jeffrey Kerby, director of UAB’s division of trauma and acute care surgery.

For patients, the experience of getting shot is emotional and unexpected, but the trauma department has to be prepared, especially these days.

Last year, UAB Hospital’s trauma team treated a record number of 1,056 people for gunshot wounds. The surge is prompting action from the wider medical community.

A Mounting Crisis

Trauma volume at UAB Hospital has been increasing for years, and not just gunshot wounds, but all injuries, including car accidents and falls.

“It’s a faucet that really, unfortunately, never stops,” said Dr. Daniel Cox, UAB’s trauma medical director.

To handle the demand, unit leaders now keep two trauma surgeons on-call in the hospital 24/7 and they hired additional nurses and fellows.

Clinicians also want to reverse the increase in gun violence.

“It’s a public health problem,” Kerby said. “It really needs a public health approach.”

The trauma surgery division is partnering with community advocates and county health officials to launch a Hospital-based Violence Intervention Program (HVIP).

Hospital Intervention

With 40 of these types of programs around the country, HVIPs connect gunshot survivors with community mentors while they are still in the hospital. Mentors help patients readjust to life after injury, linking them to resources like job placement, education and follow-up care.

Carrea Dye, an epidemiological analyst with the Jefferson County Department of Health (JCDH), is spearheading the effort to plan and implement the program in Birmingham. She said gun violence is like a disease.

“It’s preventable,” Dye said. “And in public health, one of our primary goals is to prevent disease.”

People who survive gunshot wounds are at higher risk than the general public to get injured again and die from their injuries. They are also more likely to participate in violence.

The idea behind an HVIP is to break that cycle and offer a more comprehensive approach to treating survivors of gun violence.

“They’ve experienced this trauma and they’re in their most vulnerable state,” Dye said. “And you kind of want to meet them there.”

‘Like I Never Got Shot’

JCDH officials contracted with a national advocacy group, the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention, to help guide initial development of the program. The county agreed to fund the first year, pending approval by the department’s board. They hope to begin hiring staff and launch the HVIP within the next year.

The goal is to help gunshot survivors like Quincey Sanders. He was seriously injured 18 years ago when a bullet struck him in the face, entering through the side of his nose and ricocheting out near his jaw.

Mary Scott Hodgin,WBHM

Quincy Sanders stands on the porch of mom’s house in Birmingham’s Norwood neighborhood.

Sanders spent two months in the hospital recovering. Back then, he was around a lot of guns and drugs, and he said it was hard to break away from that lifestyle.

“Once I got out of the hospital, I was back in action, like I never got shot,” Sanders said. “And I took it like that, like I never got shot. I wasn’t valuing my life.”

Sanders was eventually arrested for selling drugs. He went to prison and was released a few weeks ago.

Now he is taking classes and preparing to start a new job. It took years, but Sanders said he is on a better path. Having the support of an intervention program might have helped him get there sooner.

Officials hope having one in the future will make the way easier for other survivors.

Editor’s Note: UAB holds WBHM’s broadcast license, but our news and business departments operate independently.

American Jordan Stolz speedskates to a third Olympic medal — silver this time

U.S. speedskater Jordan Stolz had a lot of hype accompanying him in these Winter Olympic Games. He's now got two gold medals, one silver, with one event to go.

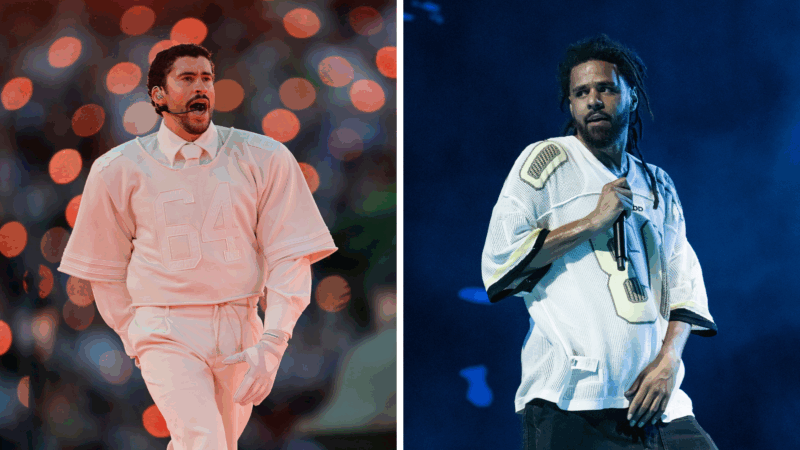

Bad Bunny and J. Cole rule the pop charts

These days, the Super Bowl halftime show is a massive driver of the streaming, airplay and sales that fuel the Billboard charts. This week, Bad Bunny benefits from that influence.

Reporter’s notebook: My Olympic Lunar New Year

An NPR reporter covering the Olympics in Milan takes us on cultural side quests, to a hospitality house and a candy store.

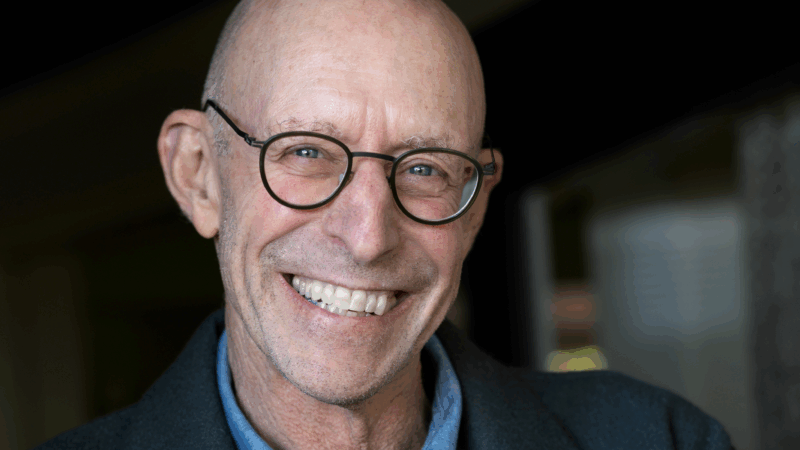

Michael Pollan says AI may ‘think’ — but it will never be conscious

"Consciousness is under siege," says author Michael Pollan. His new book, A World Appears, explores consciousness on both a personal and technological level.

The U.S. and Canada set to square off in Olympic women’s ice hockey gold medal match

Canada was long the top dog of Olympic women's hockey. But with a win Thursday, the Americans could do more than earn a third gold medal — they could prove the sport's balance of power has shifted.

Amazon dethrones Walmart as the world’s biggest company by sales

In a slow-motion race of two retail behemoths, Amazon's trump card was its lucrative cloud-computing business.