Super Outbreak of ’74

“I jokingly said, ‘I hope we don’t fool around and get blown away. I don’t think I’ve ever made that comment since that day.”

That’s because just hours later, Frye’s own house would be blown apart by some of the strongest winds known to man.

“You could hear the house creaking, the windows, the wind – it was, I don’t know how to describe it – it was an eerie feeling. It was just seconds. It seemed like a lifetime at the moment but it was here and gone in seconds.”

It was a massive tornado – an F5, the worst that can strike — that sent debris flying everywhere and a path of destruction that stretched back into Mississippi. The vast majority of Guin, a town of about 2-thousand people, was turned upside down by the monstrous storm.

Buildings were blown off their foundations. Cars and buses were thrown around like toys. Trees were uprooted. 23 people died. More than 250 were injured. When rescuers and state troopers arrived on the scene, they couldn’t believe their eyes.

“They said – quote – much of Guin is wiped off the map, so we knew then the extent of the disaster.”

J-B Elliott was one of a handful of meteorologists working at the National Weather Service office in Birmingham that night, monitoring that and several other powerful tornadoes that struck Alabama. The only tools at his disposal: ham radio operators, some teletype equipment and a phone line between his office and weather radar operators 40 miles away in Centreville. Elliott’s office didn’t even have a radar monitor.

“All we had was a facsimile reproduction of the radar scope. And the radar operators in Centreville would write notes on the radar scope and it would come over the facsimile, so we would see notes that they’d written there about where the strongest cells were…”

…a piece of white paper with a bunch of black marks. More like a Rorschach splotch test than radarscope. And the information on it was minutes-old.

The way the warnings got disseminated was even more antiquated. Messages on the Teletype wire would go out – but it would take a few more minutes to reach radio and TV stations and civil defense officials. By today’s standard: not very efficient.

But over the past 30 years – and to a degree, because of the 1974 outbreak, advances in technology and information have led to quicker weather warnings.

One example of the progress: Doppler radar – which has been online at the National weather Service for more than 15 years. It is light years more sophisticated than the old radar system that only showed various levels of rainfall.

“Instead of just seeing the precipitation, we can look at the winds. We can actually tell if the winds are going away, coming towards us, and that’s huge for tornado warnings, cause we can hopefully get the tornado before it touches down.”

Ken Graham is Meteorologist-in-Charge at the National Weather Service Birmingham office. He says not only do they have Doppler technology that can shave tornado detection time, but every forecaster has access to that information instantly on their desktops.

And the less time it takes the forecaster to find and decipher the information and get the information out, the more lives that can be saved.

But only if the public’s tuned in.

“Thank you for listening to weather radio, the voice of the national weather service, brought to you by the National Weather Service Birmingham office.”

It wasn’t until after the deadly 1974 outbreak – which killed more than 300 people — that the federal government made a concerted effort to proliferate NOAA weather radio – or National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: more than 850 transmitters across the country that broadcast National Weather Service information -from local forecasts to weather and national emergencies.

The National Weather Service’s Graham says it is one of the best and most underused tools available in severe weather preparedness.

“There’s nothing else out there that’ll wake you up when severe weather strikes. Nothing.”

Graham says because bad weather can strike anytime – the Guin tornado happened at 9:04 at night – people need to be in a place where they can receive weather information. And in order to do that, they need to know when bad weather is threatening.

“We could issue tornado warnings until we’re blue in the face, but unless somebody gets that warning and knows what to do with that warning, preparedness wise, it’s hard to prevent a fatality.”

Graham says according to recent studies, only a small percentage – around 4 percent — of the public owns a weather radio. Yet the number of tornado deaths dropped from nearly a thousand during the 1970s to 579 during the 1990s.

That’s a testament, says J-B Elliott, not only to weather radio but also to the media as a whole.

“The warnings are better now. The coverage and the amount of information is more readily available and more constant and more continuous. And back in 1974, even when we went on-the-air with a tornado warning, we would give the warning, but it was just that. You had the warning and we do some updates later, but it wasn’t any continuous broadcast.”

Forecasters say the tornado outbreak of early April 1974 was a wake up call for more technology and more ways of getting the information out. They agree that with Doppler radar, instantaneous computer information, storm spotters and weather radio, the chances of another April 3, 1974 are slim… but only if the public utilizes all that information and technology.

And forecasters say that weather radios should be a fixture in every home just like smoke detectors or telephones. They hope that by improving communication – through instant alerts on desktops, cell phones, pagers and personal digital assistants – more people will hear the warnings and heed them.

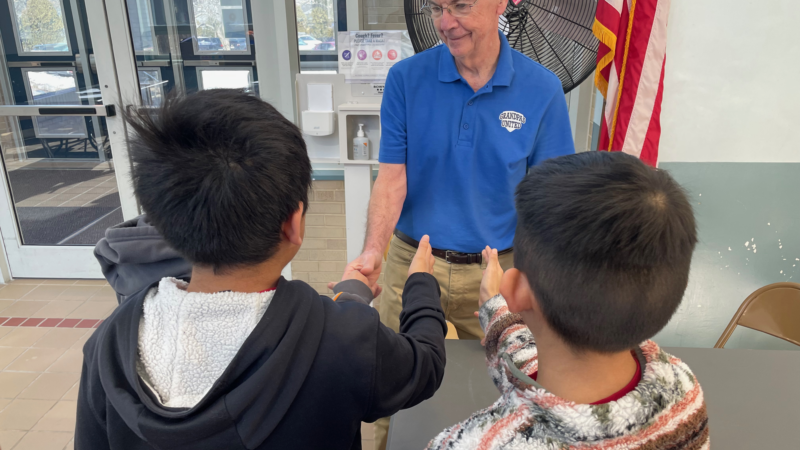

‘Grandpas’ got together to help kids. Scientists say it boosts the elders’ health, too

Older men can find themselves isolated after retirement. Volunteer groups like Grandpas United are good for both physical and mental health.

WATCH LIVE: NPR, PBS heads answer lawmakers’ allegations of bias

The CEOs of the largest U.S. public broadcasting networks are appearing before a House subcommittee chaired by Republican Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene.

DOGE says it needs to know the government’s most sensitive data, but can’t say why

DOGE staffers have skirted privacy laws, training and security protocols to gain virtually unfettered access to financial and personal information stored in siloed government databases.

Top-seeded Auburn brushes off late-season lull to make Sweet 16 with contributions abound

Now, Auburn is in its first Sweet 16 since 2019 looking to top that Final Four run with its first national championship.

‘Felt like a kidnapping’: Wrong turn leads to 5-day detention ordeal

A Guatemalan immigrant without legal status says she took a wrong turn on a highway near the Canadian border and was detained with her two children, who are American citizens. They were held for five days.

Buying or selling on StubHub? It’s probably not showing you all the available tickets

StubHub has a "Recommended Tickets" filter that only displays some tickets but not others. It's automatically turned on — and it's upsetting users.