EXPLAINER: What medical treatments do transgender youth get

Barbara Dale, from Atlanta, mother of a transgender child, waves sign reading "Love Knows No Gender" at Gay Pride Transgender March at Piedmont Park in the city's Midtown District in Atlanta, Ga, Saturday, Oct. 12, 2019. Transgender medical treatment for children and teens is increasingly under attack in many states, labeled child abuse and subject to criminalizing bans. But it has been available in the United States for more than a decade and is endorsed by major medical associations.

By LINDSEY TANNER AP Medical Writer

Transgender medical treatment for children and teens is increasingly under attack in many states, labeled child abuse and subject to criminalizing bans. But it has been available in the United States for more than a decade and is endorsed by major medical associations.

Many clinics use treatment plans pioneered in Amsterdam 30 years ago, according to a recent review in the British Psych Bulletin. Since 2005, the number of youth referred to gender clinics has increased as much as tenfold in the U.S., U.K, Canada and Finland, the review said.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health, a professional and educational organization, and the Endocrine Society, which represents specialists who treat hormone conditions, both have guidelines for such treatment. Here’s a look at what’s typically involved.

Puberty Blockers

Children who persistently question the sex they were designated at birth are often referred to specialty clinics providing gender-confirming care. Such care typically begins with a psychological evaluation to determine whether the children have “gender dysphoria,” or distress caused when gender identity doesn’t match a person’s assigned sex.

Children who meet clinical guidelines are first offered medication that temporarily blocks puberty. This treatment is designed for youngsters diagnosed with gender dysphoria who have been counseled with their families and are mature enough to understand what the regimen entails.

The medication isn’t started until youngsters show early signs of puberty — enlargement of breasts or testicles. This typically occurs around age 8 to 13 for girls and a year or two later for boys.

The drugs, known as GnRH agonists, block the brain from releasing key hormones involved in sexual maturation. They have been used for decades to treat precocious puberty, an uncommon medical condition that causes puberty to begin abnormally early.

The drugs can be given as injections every few months or as arm implants lasting up to year or two. Their effects are reversible — puberty and sexual development resume as soon as the drugs are stopped.

Some kids stay on them for several years. One possible side effect: They may cause a decrease in bone density that reverses when the drugs are stopped.

Hormones

After puberty blockers, kids can either go through puberty while still identifying as the opposite sex or begin treatment to make their bodies more closely match their gender identity.

For those choosing the second option, guidelines say the next step is taking manufactured versions of estrogen or testosterone — hormones that prompt sexual development in puberty. Estrogen comes in skin patches and pills. Testosterone treatment usually involves weekly injections.

Guidelines recommend starting these when kids are mature enough to make informed medical decisions. That is typically around age 16, and parents’ consent is typically required, said Dr. Gina Sequiera, co-director of Seattle Children’s Hospital’s Gender Clinic.

Many transgender patients take the hormones for life, though some changes persist if medication is stopped.

In girls transitioning to boys, testosterone generally leads to permanent voice-lowering, facial hair and protrusion of the Adam’s apple, said Dr. Stephanie Roberts, a specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital’s Gender Management Service. For boys transitioning to girls, estrogen-induced breast development is typically permanent, Roberts said.

Research on long-term hormone use in transgender adults has found potential health risks including blood clots and cholesterol changes.

Surgery

Gender-altering surgery in teens is less common than hormone treatment, but many centers hesitate to give exact numbers.

Guidelines say such surgery generally should be reserved for those aged 18 and older. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health says breast removal surgery is OK for those under 18 who have been on testosterone for at least a year. The Endocrine Society says there isn’t enough evidence to recommend a specific age limit for that operation.

Outcomes

Studies have found some children and teens resort to self-mutilation to try to change their anatomy. And research has shown that transgender youth and adults are prone to stress, depression and suicidal behavior when forced to live as the sex they were assigned at birth.

Opponents of youth transgender medical treatment say there’s no solid proof of purported benefits and cite widely discredited research claiming that most untreated kids outgrow their transgender identities by their teen years or later. One study often mentioned by opponents included many kids who were mistakenly identified as having gender dysphoria and lacked outcome data for many others.

Doctors say accurately diagnosed kids whose transgender identity persists into puberty typically don’t outgrow it. And guidelines say treatment shouldn’t start before puberty begins.

Many studies show the treatment can improve kids’ well-being, including reducing depression and suicidal behavior. The most robust kind of study — a trial in which some distressed kids would be given treatment and others not — cannot be done ethically. Longer term studies on treatment outcomes are underway.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Birmingham is 3rd worst in the Southeast for ozone pollution, new report says

The American Lung Association's "State of the Air" report shows some metro areas in the Gulf States continue to have poor air quality.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

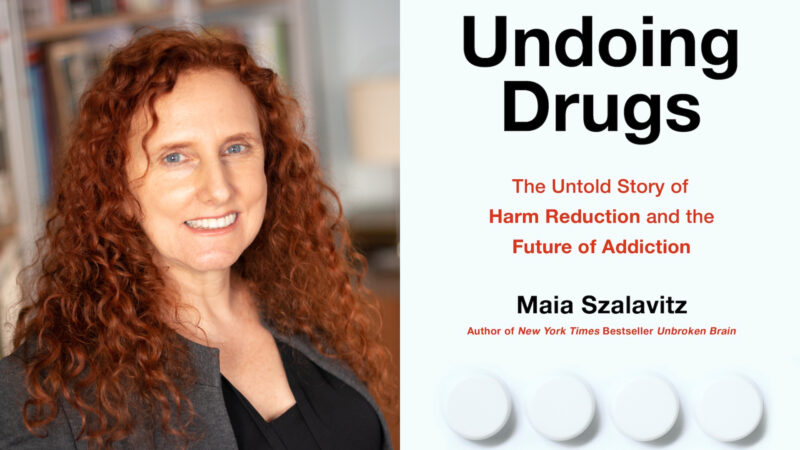

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.