This spiky-stemmed invasive grass is taking over Alabama

On his family’s land in rural Etowah County, Nick Jackson grows loblolly pine trees among a diverse range of vegetation, from oak trees to blueberry bushes.

But in 2016, a new species popped up on the property.

“We were doing site prep for planting loblolly pine, and we noticed a circular pattern of grass that was different in color to the surrounding area,” Jackson said. “That’s what triggered us to investigate a little bit further. And it was cogongrass.”

Cogongrass is an invasive plant that easily spreads and aggressively crowds out native species. And despite statewide mitigation efforts, it’s taking over Alabama.

Not your typical grass

At first glance, there’s nothing especially unique about cogongrass. Its thin green leaves stretch several feet high and produce fluffy, white dandelion-like seeds in the summer. The grass grows in thick, circular patches with intricate underground webs of spiky stems known as rhizomes.

“It’s so thick, it chokes out all the natural plants and grasses that the ecosystem is dependent on. So this has a large impact on the diversity and health of the ecosystem,” Jackson said.

Where cogongrass grows, few species survive. No crops. No timber. And the grass is really hard to get rid of.

“It’s one of the top ten worst weeds in the world, and it’s a weed everywhere,” said Nancy Loewenstein, an extension specialist with Auburn University.

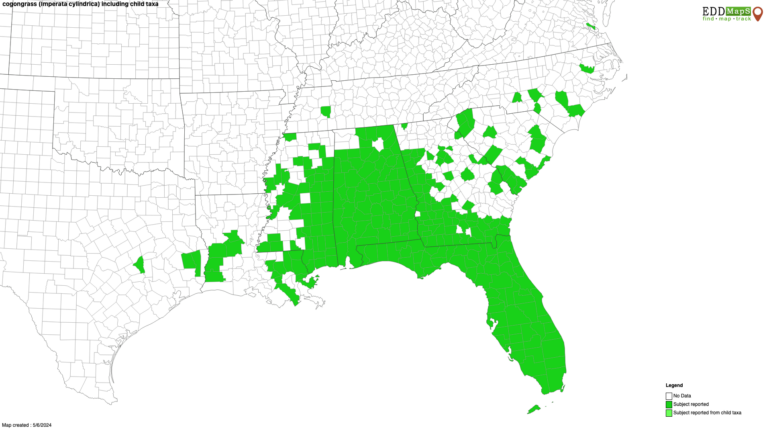

Loewenstein has studied cogongrass for nearly two decades. She said the species entered the US in the early 1900s through the port of Mobile and spread under the radar for decades.

“For the longest time it can appear that you don’t really have a problem,” Loewenstein said. “And then the population gets to such a point where it starts spreading really rapidly. And all the sudden it’s like, ‘Good grief. This stuff is everywhere. How’d that happen?’”

Alabama is at that point.

What doesn’t kill it, makes it stronger

Today, cogongrass is found in 62 of Alabama’s 67 counties and has especially saturated the southern part of the state.

Part of what makes cogongrass such a well-adapted species is that it evades many mitigation strategies.

Animals don’t eat the grass, because it’s difficult to digest. Landowners can’t mow it away, because that could stir up the underground rhizomes, which can break off and sprout new cogongrass infestations.

Burning the plant is also off the table.

“It’s a fire-adapted species, so fire actually contributes to its spread and its vigor,” Loewenstein said.

The most effective way to get rid of cogongrass is treating it with herbicides, which can be a controversial approach, according to Emma McKee, invasive species coordinator with the Longleaf Alliance.

McKee works with landowners in southern Alabama who face cogongrass infestations and said sometimes they are against spraying chemicals on their property.

“But by the end of my 10-minute spiel about how intense this plant is, they’re on board with using the herbicide,” McKee said.

Drawing a line in the sand

When applied carefully and correctly, landowners like Jackson said the treatment is worth it.

In 2022, Jackson signed up with a new program offered by the Alabama Forestry Commission (AFC). For three years, the agency sends people to his property to spray the cogongrass infestation once a year at no charge.

“They’ve done a great job,” Jackson said. “They (the AFC) can control how they spray very precisely. They limit any overspray or undesirable mortality of the native vegetation.”

Jackson said the herbicides have helped kill some of the cogongrass patch, and have stopped the species from expanding further on his property.

That’s likely the best outcome, according to Loewenstein. She said across much of south Alabama, cogongrass has spread so much, it’s unlikely landowners will be able to get rid of it. But there is still time to protect land in the northern part of the state.

“We know how to not spread it,” Loewenstein said. “So if we can make a line in the sand … let’s keep it from spreading further.”

Gen Z is afraid of sex — and for good reason

Gen Z is in a sex recession. Not because they're less horny, but because they're more afraid.

Nigeria says it won’t accept U.S. deportees: “We have enough problems of our own”

Nigeria's government is pushing back against U.S. efforts to send them migrants and foreign prisoners, with Nigerian Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar quoting Public Enemy to drive home his point.

Wet Leg are back with a slick new record

The English band's sophomore album, moisturizer, is out today. Co-founder Rhian Teasdale joins World Cafe to talk about it.

Judges to weigh request to put Alabama under preclearance for a future congressional map

Black voters and civil rights organizations, who successfully challenged Alabama’s congressional map, are asking a three-judge panel to require any new congressional maps drawn by state lawmakers to go through federal review before being implemented. The Alabama attorney general and the U.S. Department of Justice oppose the request.

Sumy, a center of Ukrainian culture, lives in the crosshairs of a new Russian offensive

The northern regional capital has become a frequent target of Russian drones, missiles and guided bombs. Now, Ukraine's top general says at least 50,000 Russian troops have massed across the border.

Take a peek at Stephen Sondheim’s papers, now at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress' new collection includes more than 5,000 items from the Broadway legend, including ideas for Sweeney Todd lyrics and notes for Glynis Johns as she sang "Send in the Clowns."