Medicaid coverage is expanding into prisons in 2025, starting with children

Community health worker Ron Sanders, right, helps a patient at San Francisco’s Southeast Family Health Center, part of the Transitions Clinic Network that assists former inmates navigate health care after release. A new policy allows states to provide Medicaid health care coverage to inmates for specific services 30-90 days before their release.

New requirements for how Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) agencies provide services for young people who are incarcerated are set to take effect in January 2025.

The change stems from new requirements from the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023. The federal policy also opens the door to extending prerelease coverage to incarcerated adults.

For decades, Medicaid’s inmate exclusion policy has left many without access to comprehensive health services during incarceration, save for limited inpatient hospital care.

People who are incarcerated often face significant health disparities compared to the general population. They are disproportionately affected by chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, as well as infectious diseases like hepatitis C, tuberculosis and HIV. Additionally, mental health conditions and substance use disorders are highly prevalent.

These disparities are compounded by socioeconomic factors such as poverty, limited access to preventative care, and systemic inequities. Black and Hispanic individuals, who are incarcerated at higher rates, often face these challenges more acutely, further exacerbating disparities in health outcomes.

Extending Medicaid to incarcerated populations addresses these disparities by ensuring access to consistent and comprehensive health care.

“This is really the first time Medicaid is being used to cover some health services for people who are incarcerated,” said Elizabeth Hinton, an expert on Medicaid policy at KFF, a nonpartisan health policy research group.

Starting with youth

The new policy applies to Medicaid- and CHIP-eligible youth under 21 and former foster youth eligible for Medicaid until age 26.

It aims to address the significant health disparities faced by this population, who often report high rates of adverse childhood experiences like abuse and neglect, linked to poor health outcomes such as substance use disorder and premature death.

Under the new policy, Medicaid and CHIP must provide medical, dental and behavioral health screenings, as well as diagnostic services, within 30 days before release. Case management will also be covered 30 days pre- and post-release, including community referrals and needs assessments.

Hinton points out that these systemic challenges call for “forging new relationships between Medicaid and corrections institutions,” requiring operational coordination at an unprecedented scale.

“The goal of these policy changes,” Hinton says, “is to ensure smoother transitions at reentry, to establish connections to community providers, and to promote access to care and support.”

Extending care to adults

Federal policy has also expanded to allow Medicaid waivers for prerelease services for adults.

Under Section 1115 waivers, states can now seek approval to provide coverage for case management, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for substance use disorders, and a 30-day supply of prescription medications at release.

As of now, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has approved waivers in 11 states, with 15 more applications pending. In the Gulf South, Louisiana is the only state to have submitted a waiver, which is currently pending.

Hinton notes that while CMS sets minimum requirements, states have the flexibility to tailor their waivers, with prerelease coverage periods ranging from 30 to 90 days.

“We’ve seen states go beyond minimum requirements to target specific populations and extend coverage,” she said, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion has played a pivotal role by allowing states to cover childless adults, further broadening the pool of eligible individuals.

Addressing racial disparities

The policy update holds promise for addressing long-standing racial health disparities exacerbated by incarceration.

By improving access to prerelease services, Medicaid coverage can help reduce these inequities and potentially serve as a model for addressing other underserved populations’ needs.

“We know there are racial disparities in incarceration that further exacerbate health disparities,” Hinton said.

Challenges ahead

Implementing these programs, however, comes with significant hurdles.

Hinton said implementing prerelease services will require new partnerships between systems like CMS and state corrections offices, providing technical assistance and ensuring systems are in place to share data.

CMS has expressed a preference for community-based providers over carceral providers to facilitate a “warm handoff” in the transition to care post-release, but building this infrastructure requires cooperation among historically siloed systems.

And while these policies have bipartisan support, their implementation could shift with the incoming Trump administration. Hinton said demonstration waivers — which would allow states to test innovative or experimental projects within their Medicaid programs that aim to improve care delivery, increase access to care, or reduce costs — are an area where administrations can assert their priorities.

For instance, the Biden administration’s guidance emphasizes health-related social needs and expedited waiver approval, but a future administration could alter these priorities.

Why this matters

At its core, this expansion underscores the importance of health care access for justice-involved individuals.

As Medicaid expands into carceral settings, Hinton said it opens the door to more equitable health care systems and strengthens the safety net for some of society’s most vulnerable populations.

“The fact that these folks who are incarcerated have such high physical and behavioral health needs, and the transition back to the community is such a vulnerable time, is really at the crux,” Hinton said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.

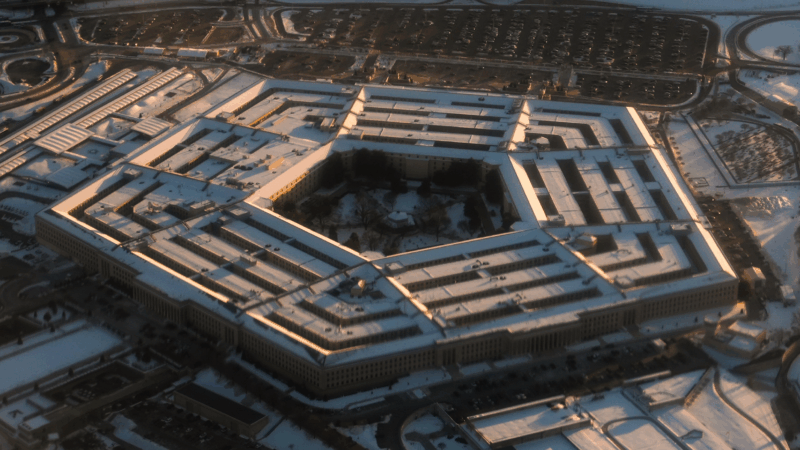

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

A new film follows Paul McCartney’s 2nd act after The Beatles’ breakup

While previous documentaries captured the frenzy of Beatlemania, Man on the Run focuses on McCartney in the years between the band's breakup and John Lennon's death.

An aspiring dancer. A wealthy benefactor. And ‘Dreams’ turned to nightmare

A new psychological drama from Mexican filmmaker Michel Franco centers on the torrid affair between a wealthy San Francisco philanthropist and an undocumented immigrant who aspires to be a dancer.