IVF could help her start the family she wants. Will Alabama’s personhood law derail it?

Gabbie Price stands next to her camper home in Moody, Alabama, on March 15, 2024. Price and her husband sold their home and moved into the 215-square-foot camper that sits on a relative’s land to pay for fertility treatments.

Gabbie Price, 26, is a planner. She grew up in a big family in rural Alabama, and it’s been her dream to have one of her own someday.

She and her husband Brady, 25, married young at 19, moving in together just after high school. And even though they weren’t ready to start their family just yet, Price got a head start and made an appointment with her doctor.

“I already knew what I wanted, and I’m not shy about saying what I want,” she said.

The young couple had lived together for less than a month when she was diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome, a hormonal condition that can cause small cysts to form on the ovaries. It doesn’t make conception impossible, just harder.

“The doctor’s exact words to me were, you are going to have a really difficult time conceiving, even with medical intervention,” Price said.

The Prices spent the next few years trying all the best strategies for pregnancy, like ovulation tests and home remedies such as “seed cycling,” but to no avail.

“I was at a point where I was taking ovulation tests every single day for months in a row and never got the slightest bit of a line,” Price said.

Then, her doctor suggested fertility treatments, but the Prices’ insurance didn’t cover them. Medicated cycles and procedures like Intrauterine Insemination, or IUI, where sperm is directly inserted into the uterus using a thin catheter, are expensive — almost $2,000 a pop — and it can take multiple cycles.

Still, Price was adamant about having a family, and quickly formulated a plan to cover the out-of-pocket costs.

They sold their home in Pinson, Alabama, which Price described as “very large, very beautiful,” and moved into a small, Palomino camper parked on a family member’s rural land in Moody, Alabama in January 2023. They remodeled it, installing a bed and a washer and dryer inside their new 250-square-foot living space.

“I truly believe there’s no way that we would have been able to go through these treatments had we not lived in this camper,” Price said.

Their plan seemed to be working. After their third IUI with a medicated cycle in December, Price finally got those two lines on a pregnancy test she’d been waiting to see.

But something went wrong. A month later, she had a miscarriage. She was at work when it happened, teaching students with disabilities at a local high school.

“There was just so much physical and mental anguish that I wasn’t prepared for,” Price said.

After her miscarriage, Price’s doctor threw out one last lifeline — in vitro fertilization, or IVF, a procedure where eggs and sperm are combined in a lab and the resulting embryos are placed into the uterus to achieve pregnancy.

The doctor called it their best shot at a successful pregnancy, but it came with a hefty cost of more than $15,000. Despite this, the Prices decided to go for it. Price even changed jobs for one that offered benefits that specifically included fertility treatments. Those benefits would kick in on March 1, so she made an appointment to start IVF treatments soon after.

But another wrench was thrown into her plans when, in February, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos can be considered children. The anti-abortion legal opinion opened to door for potential prosecution if frozen embryos are damaged, destroyed, or something goes wrong during a procedure — which caused fertility clinics across Alabama, including Price’s, to shut down their IVF treatments.

Not willing to stand idly by, Price took the issue to her representatives, joining a rally with other patients and concerned doctors at the Alabama State House in Montgomery, Alabama, on Feb. 28.

Under mounting public pressure and after a legislative scramble, Alabama lawmakers and Gov. Kay Ivey passed a law meant to protect providers of IVF from prosecution. Many clinics, including Price’s, have resumed treatments.

But the underlying court ruling that frozen fetuses have the same rights as a person — a legal concept known as personhood — is still state law. Because of this, Price said she and others are worried about what could happen to any embryos she creates, and that IVF could be shut down again.

If that happens, she doesn’t have the money or the means to travel out of state to continue her treatments.

“It is a little bit terrifying for me,” she said, “there are a lot of us, patients and doctors alike, that are really worried about how far this is going to go.”

‘Tremendous consequences’

Advocates say people like Price are right to be worried.

“Personhood comes with tremendous consequences,” said Michelle Colón from Sisters Helping Every Woman Rise and Organize (SHERo), a reproductive justice organization. “One of which is what we’re seeing now — this threat to access of IVF.”

For years, Colón said she and others have been saying that anti-abortion legislation — such as one passed in Alabama in 2018 — could affect procedures like IVF and have other unintended consequences.

Personhood laws are on the books in over a third of U.S. states. Advocates like Colón are concerned because they could be used to prosecute pregnant people for miscarrying or for potentially undergoing necessary medical procedures. Their impact on IVF in Alabama could just be the beginning of the fallout from legally defining embryos as people.

For Colón, the impacts extend much further and may jeopardize other family planning methods, like the use of contraceptives.

A ‘slap in the face’

After the Alabama Supreme Court ruling, politicians found themselves under pressure to save IVF. While the Alabama State Senate and House of Representatives argued over what to do, Price was glued to the livestreamed debates.

She watched eagerly, hoping to hear some good news, but felt frustrated when she heard some legislators trivialize IVF as a “rich, white lady problem” and claim that it didn’t affect their constituents.

“I feel like that is very uninformed,” Price said. “There are people that are being completely removed from something that truly does affect them.”

Price, who is white, is in a Facebook group with other prospective parents who are saving all they can to afford IVF treatments — some of them also live in campers like her.

It’s a diverse group, she said, with people from different backgrounds.

“I don’t consider any of the women that I know going through this as rich women,” Price said, adding that some of the Black women in the group said hearing those sentiments during the debates felt like a “slap in the face.”

In the past, IVF access wasn’t a real concern for Black and brown women because it wasn’t accessible to them, Colón said. But in her work with SHERo, she’s seen that change.

“We can no longer say that it’s just a white woman’s issue because I know a lot of Black women and other families of color that have utilized IVF,” she said. “It doesn’t matter to me who wants to use it, or who needs to use it, or who can afford it. It’s another option for people to plan their families.”

Political pawns

A KFF study found an estimated 10% of women report that they or their partners received medical help to become pregnant — that’s roughly the same percentage of left-handed people. But despite the need for fertility services, fertility care in the U.S. is often not covered by private insurers or public ones, like Medicaid.

This is true in Alabama as well. Most patients have to pay out of pocket for fertility treatment — like Price — which can add up to well over $10,000 on average.

Usha Ranji, the associate director of the Women’s Health Policy team at KFF who co-authored the study, said that fertility assistance is often misrepresented, like many other women’s health issues.

“There have been misconceptions often that people of color, particularly women who are Black, don’t need fertility assistance nearly as much as much as other people,” Ranji said. “And I think that isn’t grounded in any sort of science or data or evidence.”

Ranji said it’s part of a history of stigma, bias, and racism that undergirds parts of our health care system.

“Those misconceptions have played out so that the inequities in terms of access to something like IVF and fertility assistance, generally, have gotten really wide,” she said.

For Colón, the issues around IVF and reproductive rights boil down to bodily autonomy.

“It’s about women having a say over their own bodies,” she said. “It’s not something that should be destroyed, picked apart, played with and used as a pawn in a political game.”

Best hope

Former Alabama U.S. Sen. Doug Jones is intimately familiar with these issues. He saw personhood come up during debates around abortion, back when Roe v. Wade was in place. With Roe as a “backstop,” conservative politicians passed laws that were more “symbolic than serious.”

“They want to send a political message that is the right political message for them in the moment,” Jones said. “And they don’t have any thought to the potential consequences of what would happen.”

One of those “consequences” was access to IVF. Jones said that despite warnings from advocates like Colón, the state’s most conservative politicians did not think anti-abortion legislation would affect IVF.

“I think most of them really believe that,” Jones said. “It really shows you how dumb some of these legislators are.”

Now, with the Supreme Court ruling that embryos are children still unaddressed in Alabama, Jones is concerned that the IVF protection law amounts to little more than a “Band-Aid” that will be ripped off by a future lawsuit.

That worry — that something could again derail IVF in Alabama — is something that people like Price have to think about when they consider starting a family using the expensive treatments.

So, once again, Price is paying close attention to the legislative session. She follows the news and watches every debate she can.

But despite all this uncertainty, Price isn’t letting go of her dream.

“We are really, at this point, just ready to start our family,” she said.

IVF is their best hope. She knows the future of her family also lies in the hands of the state, but she’s not letting her fear derail her plans.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.

Mariah Carey, coffee makers and other highlights from the Olympic opening ceremony

NPR reporters at the Milan opening ceremony layered up and took notes.

Trump’s harsh immigration tactics are taking a political hit

President Trump's popularity on one of his political strengths is in jeopardy.

A drop in CDC health alerts leaves doctors ‘flying blind’

Doctors and public health officials are concerned about the drop in health alerts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since President Trump returned for a second term.

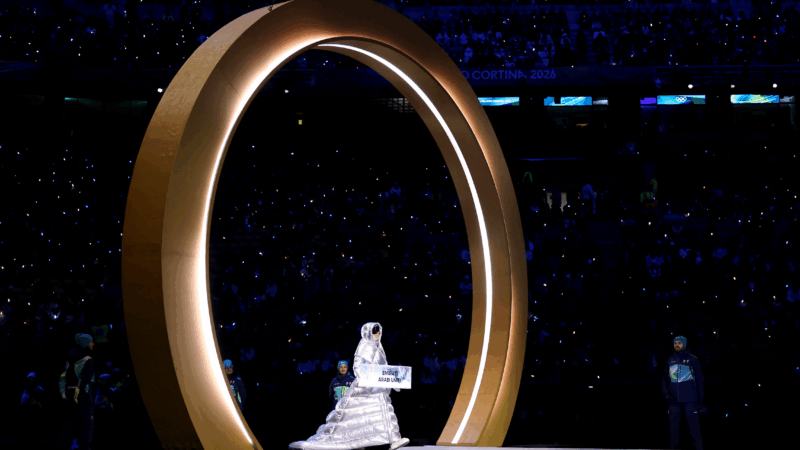

Photos: Highlights from the Winter Olympics opening ceremony

Athletes from around the world attended the 2026 Winter Olympics opening ceremony in Milan.

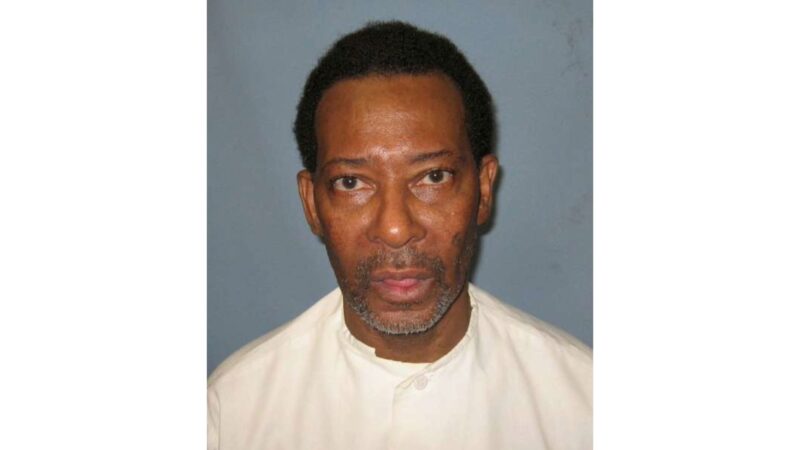

Alabama sets execution for man in auto parts store customer’s death

Gov. Kay Ivey on Thursday set a March 12 execution using nitrogen gas for Charles “Sonny” Burton. Burton was convicted as an accomplice in the shooting death of Doug Battle, a customer who was killed during an 1991 robbery of an auto parts store in Talladega.

Trump posts racist meme of the Obamas — then deletes it

Trump's racist post came at the end of a minute-long video promoting conspiracy theories about the 2020 election.