With spread of fentanyl, opioids kill record number of Black men in Birmingham

This story was co-reported by al.com’s Cody Short.

Rickey Smiley is well-known comedian from Alabama, famous for his nationally syndicated radio show where he often jokes about southern culture.

But lately, Smiley has been consumed by the much more serious issue of drug overdose.

“I walked a lady to her car at the last karaoke night at the StarDome,” Smiley said. “And she looked at me in the eye and said, ‘my son died the week before your son died.’”

Smiley’s son, Brandon, died earlier this year after taking a combination of drugs, including fentanyl. Smiley said the synthetic opioid is tearing apart his community.

“It’s bad here,” he said. “A lot of young people are showing up at the funeral home, dying of fentanyl.”

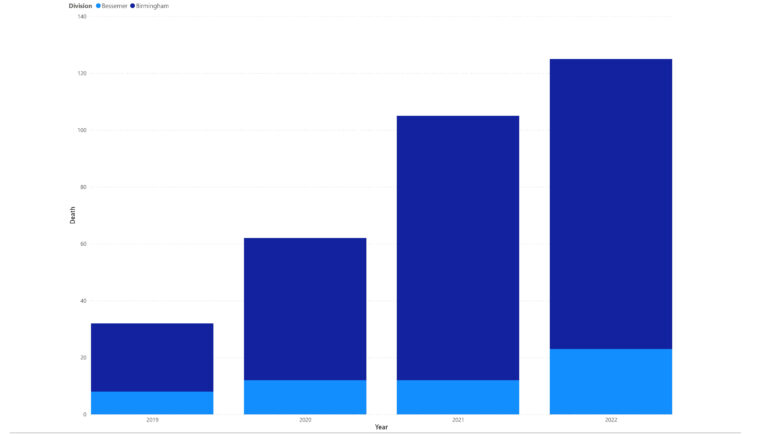

Since 2019, the number of Black men who’ve died from an opioid overdose in the Birmingham area has quadrupled.

It’s a shocking trend that’s sweeping the nation and changing the face of the opioid epidemic.

Dangerous combinations

For more than a decade, Jefferson County’s chief deputy coroner Bill Yates has followed the death toll from prescription opioids, heroin and fentanyl. Historically, white men have been most likely to die from this kind of an overdose. But around 2020, as more fentanyl hit the market, those numbers started shifting.

“The Black male demographic caught up to the white male in just a few years,” Yates said. “And it’s not just the number of deaths, what they’re dying of is what’s concerning.”

Up to 50 times stronger than heroin, fentanyl is often used to lace other drugs to increase their potency, which is what Yates has seen in many autopsies for overdose deaths among Black men.

“We were looking at the mixtures of what was in their system, and it was cocaine and fentanyl,” Yates said. “Then we started seeing, well it’s methamphetamine and fentanyl, or it’s cocaine, methamphetamine and fentanyl. And they’re all at toxic levels.”

In some cases, Yates said it’s clear people didn’t know fentanyl was mixed in with the drugs they used, a common story at local addiction recovery programs like True Vine Evangelical Ministries.

‘Ultra-devastating’

True Vine is a small operation, run out of a church nestled in Inglenook, a majority Black neighborhood in north Birmingham.

During a group session earlier this year, about half a dozen men helped Freddie Perkins celebrate several weeks of sobriety.

“I just had three consecutive clean drug tests, glory be to God,” Perkins shared.

For years, Perkins mostly used cocaine, then heroin. When he first had fentanyl, mixed with cocaine, he almost died.

“It’s a real bad drug, a scary drug,” Perkins said. “I never OD’d (overdosed) in my life, until this fentanyl stuff came around. That’s a spooky drug.”

Churches like True Vine often try to fill in the gaps where medical treatment isn’t available, according to Kady Abbott, clinical director of Fellowship House, an alcohol and drug treatment program in Birmingham.

Abbott said many people facing addiction need services like detox and medication-assisted treatment, and Black men often face more hurdles in finding that kind of care.

“Access to care, cost, affordability, awareness of a program that can actually help me – all of those are barriers,” Abbott said. “And they greatly impact Black males.”

She said Black men often experience racism in the medical system, which can lead to mistrust.

“It’s ultra devastating,” Abbott said. “And it’s compounded because we’re already experiencing disparity.”

Reaching the community

Even when resources are available, many people face a long road to recovery.

National comedian Smiley said he did all he knew for his son, entering him into rehab programs and treatment facilities, but Brandon continued to struggle with his substance use disorder.

“Kind of felt like it was just a matter of time before he either ended up in prison or dead,” Smiley said.

Smiley is now using his platform to speak out about how opioids are affecting Black families.

“It’s about trying to save lives,” he said. “Because you just can’t let your son die in vain.”

Addiction experts in Alabama say the state needs to invest in more medical treatment services and expand Medicaid. They also say treatment providers need to improve communication and outreach, to better connect with Black men struggling with substance use disorders.

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

A new film follows Paul McCartney’s 2nd act after The Beatles’ breakup

While previous documentaries captured the frenzy of Beatlemania, Man on the Run focuses on McCartney in the years between the band's breakup and John Lennon's death.

An aspiring dancer. A wealthy benefactor. And ‘Dreams’ turned to nightmare

A new psychological drama from Mexican filmmaker Michel Franco centers on the torrid affair between a wealthy San Francisco philanthropist and an undocumented immigrant who aspires to be a dancer.