New biography examines King as a person over the myth

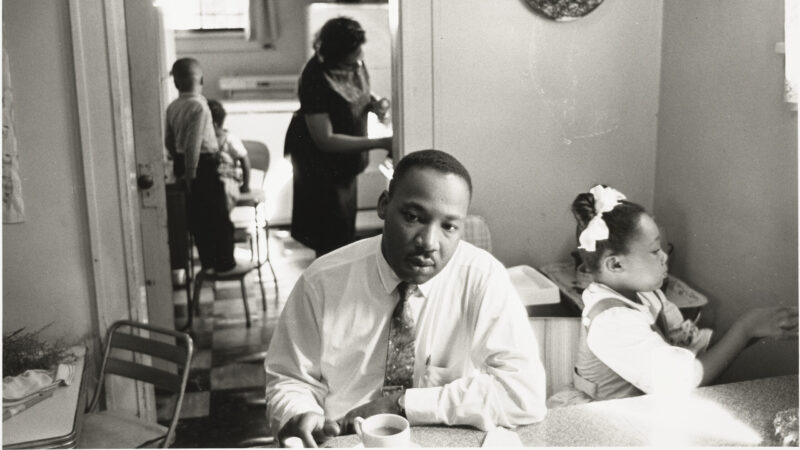

The Rev. Martin Luther King Junior chewed his fingernails. He smoked cigarettes and tried to hide it from his kids. He had a penchant for pool halls.

Those aren’t the typical details associated with the civil rights leader, but they are part of an intimate portrait of King presented in a new biography.

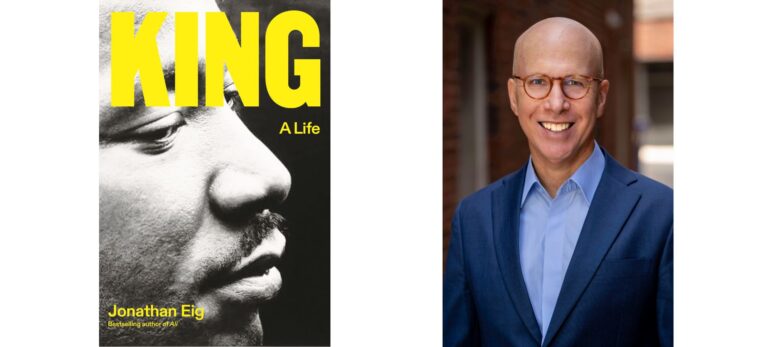

“We tend to treat him almost like this mythological figure and I wanted to write a book that would restore his sense of humanity,” said writer Jonathan Eig. “He lived and breathed and felt pain, felt a great sense of accomplishment. It wasn’t preordained. He was making stuff up as he went along and he was struggling.”

Eig’s book King: A Life is out Tuesday. It relies on a trove of new sources including thousands of declassified FBI documents, audio tapes recorded by Coretta Scott King, an unpublished memoir by King’s father and material from King’s personal archivist.

Eig said the government records reveal the extent to which the FBI tried to weaponize King’s personal life, specifically marital infidelities, to try to destroy him, and the degree to which President Lyndon Johnson was complicit in that effort.

“[Johnson] not only knew exactly what the FBI was doing, he was encouraging it. He seemed to actually enjoy the gossipy details of King’s life,” Eig said. “[This was] maybe the greatest relationship ever between a president and protest leader and I think LBJ bears a lot of the responsibility for blowing up that relationship.”

Throughout the book, Eig traces how King navigated multiple forces within the Civil Rights Movement while also dealing with internal strife.

Dr. King comes to Birmingham

When the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth invited King to come to Birmingham in 1963, the history changing events that would develop were far from assured. As Eig writes, the “mass movement lacked both mass and movement.” Still, King was trying to recreate the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

“In Montgomery it was crystal clear. We’re trying to integrate the buses. You have this dramatic scene of thousands of people walking every day to their jobs. It was very easy to see what they were asking for,” Eig said.

In contrast, campaigns in St. Augustine, Florida, and Alabany, Georgia, fell apart.

In Birmingham, organizers focused on economic issues, such as access to jobs. But Black preachers were reluctant to join in and King found it difficult to gather support. While police commissioner Bull Connor has a reputation for brutality, he initially had a restrained response to the protests, denying King the conflict needed to focus the media’s attention on Birmingham.

“It wasn’t until King desperately agreed to allow the students to [march] and that was because they couldn’t find enough people to march,” Eig said. “So that tells you something about how much he was struggling to gain traction in the city.”

Nevertheless, what became known as the Children’s March, where students were met with police dogs and firehoses, did capture the nation’s attention and became a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement. Later that year, King delivered his iconic “I have a dream” speech at the March on Washington. Eig argues King had his greatest influence during this time period.

“There’s this sense, at least in the North, maybe a more reluctant sense in the South, that change was really going to happen and that America was turning a corner,” Eig said. “Unfortunately it doesn’t last. There’s a backlash to this success. We see it just days after the March on Washington with the bomb at the [16th Street Baptist] church in Birmingham.”

An Alabamian by his side

King would not be who he became without the support of his wife Coretta Scott King. While the two met when Martin Luther King was a student at Boston University, she was born in rural Marion, Alabama. She was educated at a school in Marion with both Black and white teachers. With funding from the state of Alabama, she later studied at Antioch College in Ohio and then the New England Conservatory of Music.

“Before she meets Martin Luther King, she is an activist. She’s involved in protests on campus. I think that one of the things that really attracted Martin Luther King to Coretta is the fact she had more experience as an activist when they met,” Eig said.

Coretta wanted to stay in the North but she agreed to go with Martin back South, first to Montgomery and then to Atlanta. Eig said Coretta was always compromising her desires for Martin’s work.

King was not progressive on women’s roles either within the movement or within his marriage. He expected Coretta to take care of the home and children. Eig attributes that to the culture of the time and the culture of Black southern ministers.

“King was hearing it from his wife and he respected his wife and really admired her for her intelligence … But it didn’t translate into really letting the women have meaningful roles of leadership,” Eig said.

One theme throughout the book is what made King different. Why did he rise to become the symbol of the Civil Rights Movement? Eig said it was his unique voice.

“It sounds both radical and moderate at the same time,” Eig said.

King wove biblical ideas, familiar to many Americans, with values from the U.S. Constitution and democracy. King was not asking for a destruction of American society, but rather for the acceptance of African Americans within it.

“It’s very hard to argue with such a loving, positive, patriotic view,” Eig said. “King’s voice speaks to Black people of the South. It speaks to rich white people in the North who want to contribute. It even begins to pierce the armor of some of the white Southern segregationists who are opposed to him, because for all its radicalness, it’s also rational and seemingly reasonable.”

Extended interview with Jonathan Eig:

U.S. and Iran to hold a third round of nuclear talks in Geneva

Iran and the United States prepared to meet Thursday in Geneva for nuclear negotiations, as America has gathered a fleet of aircraft and warships to the Middle East to pressure Tehran into a deal.

FIFA’s Infantino confident Mexico can co-host World Cup despite cartel violence

FIFA President Gianni Infantino says he has "complete confidence" in Mexico as a World Cup co-host despite days of cartel violence in the country that has left at least 70 people dead.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

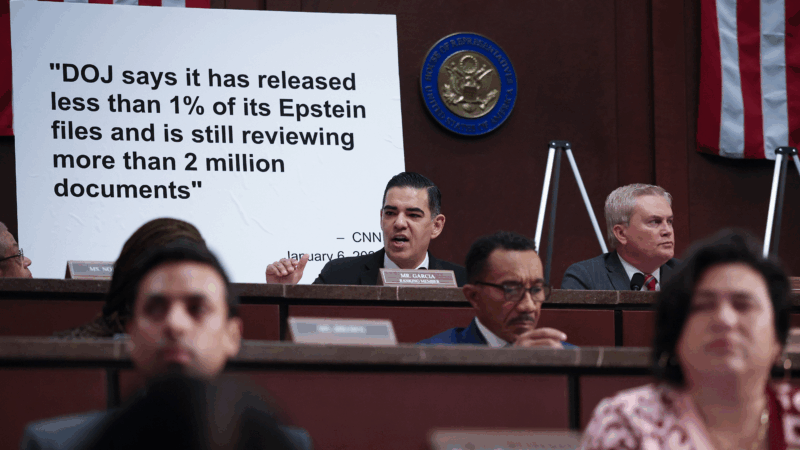

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

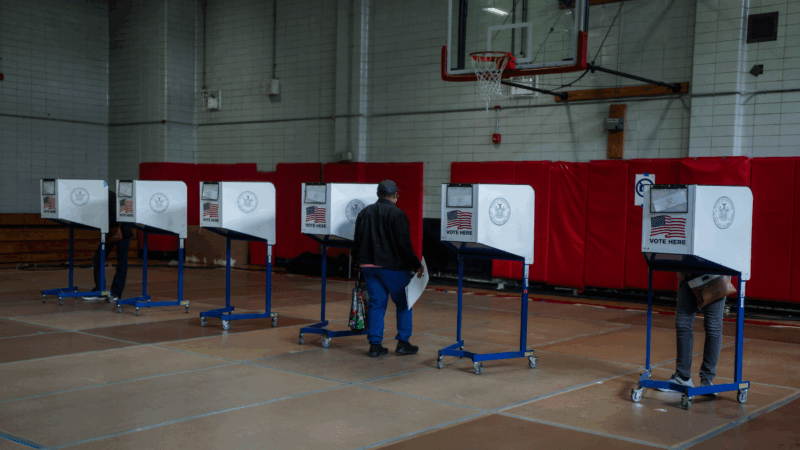

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.