In disposing coal ash, Alabama is not like other states

A coal ash pond (center) located near the Locust Fork of the Black Warrior River (foreground) at Alabama Power's Plant Miller (background) in western Jefferson County, Alabama.

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News

MONTGOMERY, Ala.—At an EPA meeting in Montgomery, a cup of water took center stage.

In a modest hotel a stone’s throw from the Alabama River, dozens of people shared their views on a serious threat to groundwater and drinking water safety with representatives of the Environmental Protection Agency. On the agenda was the EPA’s proposed denial of the State of Alabama’s plan to allow Alabama Power, the state’s largest energy utility, to continue storing coal ash in unlined ponds near waterways across the state.

Coal ash is the waste that remains after coal is burned for electricity, and is among the most environmentally costly of the long-term legacies from more than a century of burning coal.

During the public hearing on Sept. 20, those present overwhelmingly testified in favor of the agency’s proposed denial, which could result in Alabama Power being forced to remove and relocate the coal ash ponds. The EPA has proposed denying Alabama’s plan because the agency says it does not provide even the minimal protections for people and waterways required by federal law.

Among the EPA detractors was former Republican state Rep. Kyle South, who now serves as president of the Chamber of Commerce of West Alabama. At one point after he had testified, an environmental activist, Anne DiPrizio, stood behind him and poured a cup of water over his head. “You created a spectacle,” she said as the water soaked South.

“Y’all might say, ‘Oh, well, that’s crazy. That’s a crazy, unhinged lady,’” she continued. “Yeah, I might be, at this point.

While most members of the public at the hearing expressed gratitude for the EPA’s planned action, representatives of the energy industry and state-level environmental regulators testified against the proposed denial, arguing that simply capping often-unlined coal ash ponds in place is a safe, effective disposal plan.

South later told a local reporter that he testified in his capacity as a former lawmaker. He declined to speak with Inside Climate News about the incident.

The EPA announced its proposed denial of Alabama’s coal ash disposal plan in early August, saying it does little to protect humans and the environment. The decision marks EPA’s first ever denial of such a state plan.

“Exposure to coal ash can lead to serious health concerns like cancer if the ash isn’t managed appropriately,” EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan wrote in a statement at the time. “Low-income and underserved communities are especially vulnerable to coal ash in waterways, groundwater, drinking water, and in the air. This is why EPA works closely with states to ensure coal ash is disposed of safely, so that water sources remain free of this pollution and communities are protected from contamination.”

Regan announced an enforcement crackdown on coal ash pollution in January 2022 after four years of effort by the Trump administration to relax coal ash regulations.

As of 2012, more than 470 coal-fired electric utilities in 47 states and Puerto Rico had already generated about 110 million tons of coal ash, one of the nation’s largest industrial waste streams, according to the EPA.

In 2015, the agency adopted a new Coal Ash Rule, providing a series of safe disposal requirements. But a 2019 report by the Environmental Integrity Project and other advocacy groups found that 91 percent of coal-fired plants still had ash landfills or waste ponds that leak arsenic, lead, mercury, selenium and other metals into groundwater at dangerous levels, often threatening streams, rivers and drinking water aquifers.

Federal law now requires that closures of so-called coal combustion residual (CCR) units either comply with federal regulations or with state-adopted regulations that, at a minimum, are as protective of humans and the environment as the federal requirements.

So far, the EPA has approved three other states’ plans for CCR unit closure. But EPA officials, in reviewing Alabama’s plan, determined that it does not meet even those minimal requirements laid out in federal law regarding groundwater protection, monitoring and cleanup.

Coal ash, or CCR, is an umbrella term that refers to several waste materials generated by the process of burning coal for electricity production. These waste materials can include fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag and flue gas desulfurization sludge. The waste can contain chemicals that are highly toxic to humans and animals and harmful to the environment, including mercury, cadmium and arsenic, according to the EPA.

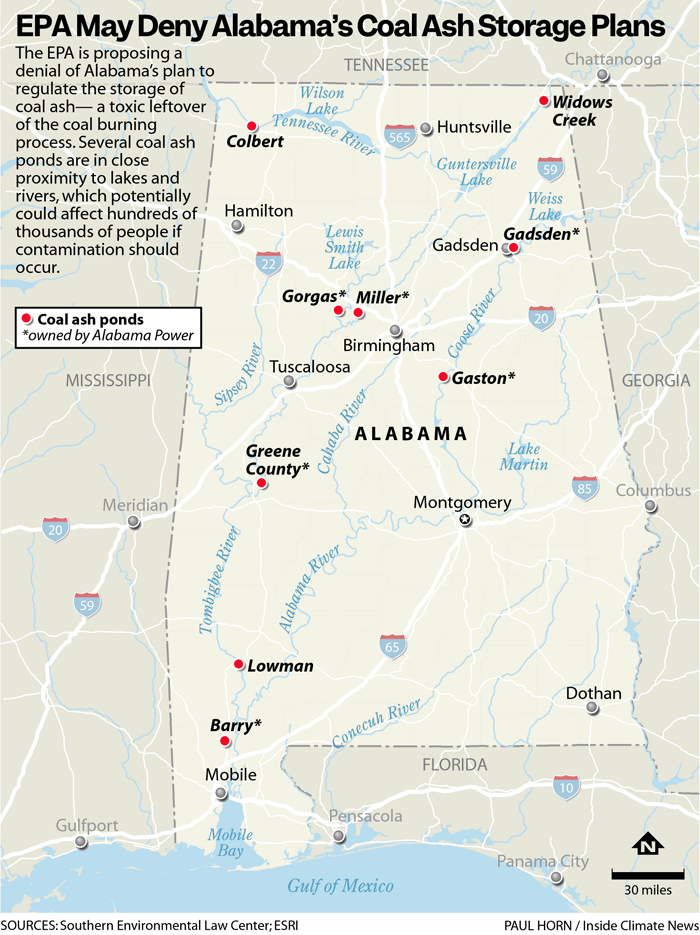

Often, energy utilities combine these waste materials with water and store them in ponds at or near electrical generating plants, a practice environmental groups have criticized as risking groundwater contamination. Currently, Alabama has nine coal ash disposal sites across the state, most of which are located near waterways.

Such storage of hazardous materials isn’t always safe, history shows.

In 2008, more than a billion gallons of toxic coal ash spilled onto 300 acres of nearby land when a dike holding the waste in a pond collapsed in Tennessee. Dozens of cleanup workers died of illnesses allegedly caused by exposure to the toxic ash during the cleanup and hundreds remain ill years later, according to a report by EarthJustice.

In 2014, a steel sewer line under a North Carolina coal ash pond collapsed, allowing the waste material to flow into the pipe and, eventually, into the nearby Dan River, polluting the water and putting dozens of marine species in harm’s way. The disaster was among more than 160 cases of water contamination at coal ash sites that spurred adoption of the Coal Ash Rule in 2015.

Energy companies generally have two options when deciding how to manage coal ash waste. “Capping” coal ash in place, the cheaper method of CCR unit closure, involves removing the water from a coal ash pond and placing a synthetic liner over the remaining waste to prevent access by rainwater. Environmental groups say this method is inferior to so-called “clean closure,” where utilities entirely remove the ash from the impoundment to a lined landfill or for beneficial reuse in products like concrete

An executive of Alabama Power, which owns most of the state’s CCR units, claimed at the September EPA hearing that the utility’s storage ponds are “structurally sound.” Susan Comensky, Alabama Power’s vice president of environmental affairs, told EPA officials that allowing the company to “cap” CCR waste in place, even in unlined pits, will not present significant risks to human or environmental health.

“Even today, before closure is complete, we know of no impact to any source of drinking water at or around any Alabama Power ash pond,” Comensky said.

However, Alabama Power has been repeatedly fined for leaking coal ash waste into groundwater.

In 2019, the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM) fined the utility $250,000 after groundwater monitoring at a disposal site on the Coosa River in Gadsden showed elevated levels of arsenic and radium, according to regulatory documents.

In 2018, ADEM fined five of Alabama Powers plants a total of $1.25 million for groundwater contamination, records show. In its order issuing the fine, the agency cited the utility’s own groundwater testing data, which showed elevated levels of arsenic, lead, selenium and beryllium.

Just last week, a federal judge in Alabama recommended that a lawsuit filed by Mobile Baykeeper, an environmental advocacy group, against Alabama Power over its coal ash pond north of Mobile Bay be allowed to move forward, providing another avenue for citizens to challenge the utility’s pollution of groundwater and other environmental impacts.

In a written rationale for denying Alabama’s permit plan, EPA officials also wrote that because of Alabama’s lax proposed regulation of coal ash ponds, which does not require permittees to comply with federal groundwater monitoring standards, additional leaks may be happening unmonitored.

Alabama’s proposed regulation of these waste sites, the EPA argued, does not require sufficient controls to prevent groundwater from flowing in and out of coal ash at the sites indefinitely. Alabama’s plan also allows facilities “to delay effective responses to contaminant releases that may pose a risk to human health and the environment.”

Since Alabama Power announced its decision to cap coal ash disposal sites in place in 2016, environmental activists at the local and national level have advocated for removing the waste near waterways and instead depositing it in landfills lined with an impermeable, synthetic material that would prevent groundwater pollution.

Industry representatives at the hearing, however, argued that moving coal ash would present a greater environmental risk than capping coal ash in place.

Frank Holleman, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, said the argument is a common ploy used by utilities who don’t want to pay for the cost of cleanup.

“We’ve heard that before. That’s an old song that we have heard when utilities are fighting effective cleanup,” he said. “But this is happening in South Carolina and North Carolina, Virginia and Georgia. In fact, there are sites in South Carolina and sites in North Carolina where this is done. It’s finished. It’s all been put in safe places and recycled in cement and concrete. And there were none of these problems. These problems do not exist.”

Lee McCarty, who served as mayor of Wilsonville from 2012 to 2020, told EPA representatives at the hearing that the continued storage of coal ash, which contaminates groundwater, is unacceptable.

“We’ve got 24 million tons of coal ash sitting in our little town of 2,000 people,” he said. “We have people’s homes—my friends, neighbors and constituents—that back right up to a three-to-five story high mound of coal ash. The coal ash pond goes right out to the river.”

McCarty said that when concerned officials and residents began attending ADEM meetings to complain about the coal ash, they were met with blank stares.

“They looked at us like stop signs,” he said.

Because Alabama Power has been granted an effective monopoly on energy production in much of the state, McCarty argued, they should be held to a higher standard, not a lower one, when it comes to complying with environmental laws.

“Alabama Power gets to dominate and bully state government and the citizenry to do basically whatever they want, whenever they want,” he said. “Now, did we learn in kindergarten that if you make a mess, you clean it up?”

The EPA’s intervention is a welcome move that may help stop that bullying, McCarty argued.

DiPrizio, the activist, waited for her turn on a speaker’s list before rising in the back of the hotel conference room. Known for previous direct actions that have led to her arrest, she felt strongly that the EPA hadn’t gone far enough in protecting Alabama’s citizens and environment.

“Alabama is dead last in the nation for drinking water quality, according to J.D. Power and Associates, 2023,” she said, a cup of water in her hand.

DiPrizio then approached South, the former Republican state representative and Chamber of Commerce executive.

“Everybody knows that this is a spectacle,” DiPrizio said of the hearing and South’s testimony. She poured the cup of water over South’s head.

“Wow,” South responded.

DiPrizio then walked to the front of the room, calling the EPA hearing a sham.

“Stop killing us,” she yelled. “Stop killing us.”

EPA officials unsuccessfully attempted to interrupt DiPrizio multiple times, eventually breaking for lunch and clearing the room to settle the situation. An EPA representative told Inside Climate News that, upon arrival, police officers asked the protester to leave voluntarily during the lunch break. She did so, the representative said, avoiding arrest.

EPA will continue to accept comments on the proposed denial of Alabama’s coal ash residuals program until Oct. 13.

Gen Z is afraid of sex — and for good reason

Gen Z is in a sex recession. Not because they're less horny, but because they're more afraid.

Nigeria says it won’t accept U.S. deportees: “We have enough problems of our own”

Nigeria's government is pushing back against U.S. efforts to send them migrants and foreign prisoners, with Nigerian Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar quoting Public Enemy to drive home his point.

Wet Leg are back with a slick new record

The English band's sophomore album, moisturizer, is out today. Co-founder Rhian Teasdale joins World Cafe to talk about it.

Judges to weigh request to put Alabama under preclearance for a future congressional map

Black voters and civil rights organizations, who successfully challenged Alabama’s congressional map, are asking a three-judge panel to require any new congressional maps drawn by state lawmakers to go through federal review before being implemented. The Alabama attorney general and the U.S. Department of Justice oppose the request.

Sumy, a center of Ukrainian culture, lives in the crosshairs of a new Russian offensive

The northern regional capital has become a frequent target of Russian drones, missiles and guided bombs. Now, Ukraine's top general says at least 50,000 Russian troops have massed across the border.

Take a peek at Stephen Sondheim’s papers, now at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress' new collection includes more than 5,000 items from the Broadway legend, including ideas for Sweeney Todd lyrics and notes for Glynis Johns as she sang "Send in the Clowns."